Late last year, on the eve of the 30th anniversary of the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russia massed troops on its border with Ukraine and issued draft agreements with the U.S. and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) spelling out demands for changes to the European security order including no further expansion of NATO. With the United States and its European allies and partners embarking on a series of pivotal negotiations with Moscow beginning January 9 in Geneva, mass protests erupted in Kazakhstan in the first week of 2022 and the Russia-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) intervened militarily at the request of Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev. What are Russian President Vladimir Putin’s intentions? How should the U.S. and its allies respond to Russia’s moves? What are the implications of the Kazakhstan uprising? Below, Brookings experts reflect on recent developments in the former Soviet Union and offer policy recommendations.

Pavel K. Baev

Pavel K. Baev

Nonresident Senior Fellow, Center on the United States and Europe

There was never a chance for a breakthrough at the U.S.-Russia talks in Geneva exacted by President Putin’s unprecedented demand for one-sided “security guarantees.” U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman spent a long seven hours checking the depth of disagreements with Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Ryabkov, who had announced beforehand that no deviations from the draft agreement published by Moscow in mid-December were possible. Russian demands for discontinuing all military ties between the United States and Ukraine were clearly unacceptable, but Ryabkov expressed satisfaction that the Russian position was taken “very seriously.” If Russia seeks to prove that its behavior will be neither stable nor predictable, despite President Joe Biden’s request presented to Putin in the same city half a year ago, it has succeeded exceedingly.

Material evidence of Russia’s propensity for reckless power projection is supplied by the swift intervention into suddenly riotous Kazakhstan on the eve of Orthodox Christmas. Only some 2,000 paratroopers were airlifted under the pro-forma aegis of the Collective Security Treaty Organization, but the appointment of General Andrei Serdyukov, the seasoned commander of Russian Airborne Troops, as the commanding officer of the operation indicated that any number of reinforcements could be forthcoming. Tense stability has been restored in protest-overwhelmed Almaty, and Russia has established for fact that it can act as security provider and order enforcer in its immediate neighborhood. This success bodes ill for Ukraine, which has to assume that Russian tanks are amassed on its borders for purposes more ominous than just supporting talks with the West.

Jessica Brandt (@jessbrandt)

Jessica Brandt (@jessbrandt)

Policy Director, Artificial Intelligence and Emerging Technology Initiative, and Fellow, Center for Security, Strategy, and Technology

On an ongoing basis, Russia uses a suite of asymmetric tools — including information manipulation and cyber operations — to weaken the European security order and undermine democratic states and institutions that could organize against its interests. This is part of its playbook for Ukraine.

In the information domain, the Kremlin is already deploying a “divide and discredit” strategy. For weeks, Russian state media and diplomats have been hammering differences between the United States and its European partners over their approach to the crisis and working to dent the credibility and appeal of NATO — an essential institution of the liberal international order — casting it as the true aggressor. This is part of a long-running strategy to weaken the trans-Atlantic partnership, undermine European cohesion, and disparage liberal institutions, including NATO. If tensions increase, Washington should expect this activity to intensify.

Meanwhile, cybersecurity experts have noted an uptick in intrusions into Ukrainian computer networks, both government and civilian, that could set the stage for a major cyberattack. That would not be without precedent. Russian hackers have previously taken aim at Ukraine’s election infrastructure and energy grid, the Kyiv Metro, and the Odesa airport, among other targets. Policymakers should take seriously the possibility of an attempt to disrupt Ukraine’s economy and government. It’s good, then, that Washington and London have reportedly sent experts to the country to help bolster its defenses against such a move.

Vanda Felbab-Brown (@VFelbabBrown)

Vanda Felbab-Brown (@VFelbabBrown)

Senior Fellow, Center for Security, Strategy, and Technology

A Russian invasion of Ukraine would constitute perhaps the greatest global security crisis in three decades. However, even should talks with Russia avert this without the West making troubling concessions to Russia’s extravagant demands, Putin will succeed in accomplishing some of his nefarious objectives. Putin’s crisis-making consumes the attention of top U.S., NATO, and European policymakers and reduces their focus on other important issues, from the crises in Afghanistan, Somalia, and Ethiopia to the slow-burning morass in Mexico or Venezuela to long-term existential matters such as preventing zoonotic diseases, preserving global biodiversity, and stabilizing the planet’s climate.

No doubt, highly competent officials with regional and functional portfolios remain focused on those issues, but the principals’ attention is depleted by their need to respond to the Putin-orchestrated crisis. Moreover, Putin can maintain such crisis-making for months, leaving troops at the Ukrainian border, withdrawing them, putting them back, and perhaps one day — during crisis number three or four or six — actually invading, undeterred by further Western economic sanctions.

Meanwhile, while tying up high-level U.S. policy focus in eastern Europe, Russia intensely meddles in some of the very places from which it diverts American attention. Across Africa, the Middle East, Asia, and even Latin America, Russia has built up a variety of tools and proxy actors — from disinformation campaign trolls to Moscow-linked “private” security companies problematically propping up regimes in exchange for security access and resources. Often Russia’s objective is simply to frustrate U.S. goals, regardless of their substantive content.

Samantha Gross (@samanthaenergy)

Samantha Gross (@samanthaenergy)

Fellow and Director, Energy Security and Climate Initiative

Both Europe and Russia have a lot to lose in the energy space if the situation in Ukraine escalates. Russia is the largest supplier of natural gas to the European Union, providing more than 40% of EU imports. Europe is now suffering through a crisis in gas supply. High demand and low storage and supply are combining to create natural gas prices 4.5 times those at this time last year, although down a bit from their highest levels in December.

On the one hand, Russia is enjoying today’s very high gas prices, an argument for stepping back from the brink. Germany has also indicated willingness to stop the nearly completed Nord Stream 2 pipeline if Russia’s aggression against Ukraine escalates. On the other hand, Europe can ill afford to lose any gas supply right now, meaning that applying sanctions on Russian gas or reducing purchases from Russia would be very painful, a situation President Putin surely understands.

On top of these strategic questions lies the security of the gas supply itself. Transit of Russian gas provided $2 billion in revenue to Ukraine in 2020, meaning that Ukraine has every reason to protect the compressors that keep the pipelines running. Russia too has reason not to damage the pipelines, since an estimated 35% of Russia’s gas exports still go through Ukraine. Despite years of building new pipelines that bypass Ukraine, the country is still central to Russia’s energy economy.

Daniel S. Hamilton (@DanSHamilton)

Daniel S. Hamilton (@DanSHamilton)

Nonresident Senior Fellow, Center on the United States and Europe

Putin’s saber-rattling is not only existential for Ukraine, it is the most visible, dangerous, and urgent sign that Europe has moved from an era of relative stability to an age of ongoing disruption.

Putin wants to undo the post-Cold War settlement, control his neighborhood, and disrupt the influence of open democratic societies, not because of what they do but because of who they are. It is useful to recall that the pretext for Russia’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine was not NATO expansion, it was a trade agreement between Ukraine and the European Union. Putin understands the challenge a successful Ukrainian democracy would pose to authoritarianism in Russia. Through his current threats and his earlier military interventions in Ukraine, his meddling in neighboring countries, and his continuing use of energy, cyber, and other instruments as political tools, his message is clear: Hard power still matters, and borders in Europe can still be changed by force. He is intent on expanding the arena of competition, not only to the post-Soviet space, but to democracies in Europe and beyond.

Today, Ukraine is the crucible of Europe’s disruption. Our most immediate challenge is to deter Russian aggression there. Tomorrow, others will be tested — and not only by Russia. New technologies are changing the nature of competition and conflict. Digital transformations are upending the foundations of diplomacy and defense. China is disrupting basic principles and arrangements critical to Europe’s security and prosperity. Europe’s earthquake did not end in 1989 or 1991. It continues to rumble.

Marvin Kalb (@MarvinKalb)

Marvin Kalb (@MarvinKalb)

Nonresident Senior Fellow, Foreign Policy

Russian armies roam the Eurasian landmass, as though they’re operating in their own backyard. That’s not to President Biden’s liking, and it certainly raises urgent questions for NATO. It seems to be putting East and West on another collision course.

In recent months, tens of thousands of Russian troops have congregated near the Ukrainian border, and in recent days thousands have actually crossed the border into Kazakhstan in an effort to crush a widespread uprising.

There are differences in Russia’s approach to these two former Soviet republics. In 2014, Russia seized Crimea and moved into the Donbas region of Ukraine. Cover stories were concocted, but Russia’s strategic intent was obvious — Moscow was trying to topple the pro-West regime in Kyiv. Russian President Vladimir Putin apparently believes history has given him a mysterious right to act. In Kazakhstan, Russia invaded as part of an international force, providing convenient cover, but again Russia’s strategic intent is obvious: to keep Kazakhstan in friendly hands.

Whether Russia might now exploit her military presence there to readjust borders is uncertain but possible. Former President Boris Yeltsin warned that Russia “reserves the right” to change her borders with Kazakhstan, and Putin maintains that “Kazakhs never had any statehood” before the Soviet collapse anyway.

A dangerous question emerges, because Putin seems serious about his reading of Russian history: How can the West challenge this notion without sliding step by step into a military confrontation with Russia, something neither side wants?

Patricia M. Kim (@patricia_m_kim)

Patricia M. Kim (@patricia_m_kim)

David M. Rubenstein Fellow, John L. Thornton China Center and Center for East Asia Policy Studies

The mounting crises over Ukraine and in Kazakhstan have raised questions about China’s stances on both, as well as implications for Sino-Russian ties and the larger geopolitical landscape. Beijing’s foremost priority is to maintain stability in its periphery as it looks to orchestrate the Winter Olympics and the 20th Party Congress, all the while struggling to maintain a zero-COVID policy.

China has adopted relatively low-key positions on both Ukraine and Kazakhstan thus far. Beijing has expressed support for Kazakh President Tokayev in his fight against “external forces,” and the dispatch of Russian troops to the former Soviet republic under the auspices of CSTO. Beijing has also avoided taking sides between Moscow and Kyiv in attempts to stay on good terms with both. While Presidents Xi and Putin used their virtual meeting in December to collectively denounce Western “interference” in their internal affairs, official Chinese readouts were careful not to explicitly reference Putin’s demands for security guarantees from NATO and the United States. Just a few weeks later, Xi sent a congratulatory message to Ukraine to mark the 30th anniversary of the establishment of bilateral ties. These developments suggest that while Beijing sees value in working closely with Moscow to push back against “Western encirclement,” it is not willing to back specific Russian core interests.

Moreover, a Russian intervention in Kazakhstan and growing Russian sphere of influence in China’s backyard are ultimately at odds with Beijing’s long-term interests. U.S. policymakers would be wise to keep these contradictions and larger picture in mind, while working to prevent further solidification of Sino-Russian ties.

Kemal Kirişci (@kemalkirisci)

Kemal Kirişci (@kemalkirisci)

Nonresident Senior Fellow, Center on the United States and Europe

As Putin resorts to military pressure on Ukraine and raises demands on the U.S. for changes to the European security order, neighboring countries are revisiting their policies towards Russia. The debate over Finland and Sweden becoming NATO members has been revived triggering promises of an “appropriate response” from Russia. The position of Turkey moving forward is also evolving.

During the last few years, under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Turkey’s relations with Russia has wavered between strategic partnership and rivalry. As late as in September, after meeting with Putin, Erdoğan reasserted his commitment to the partnership with Russia and reiterated his position on keeping Russian S-400 missiles despite U.S. sanctions. Yet Russian threats to invade Ukraine is reviving the weight of history marked by frequent wars, which Turks mostly lost, reinforced by Josef Stalin’s territorial demands in 1945 that propelled Turkey into NATO 70 years ago in February.

Recently, the geopolitical significance of NATO membership has been reiterated by two prominent retired Turkish ambassadors, a small but important uptick in importance attributed to NATO from 48% in 2020 (slide 83) to 58% in 2021 (slide 90) has been reported among the Turkish public. Possibly more significant might be Turkish efforts to shore up the defenses of Ukraine, which has drawn Putin’s ire, and Georgia. With Turkey having the second largest military in NATO and a unique geographical position commanding the Black Sea, these recent developments should be factored into formulating a response to Russian demands.

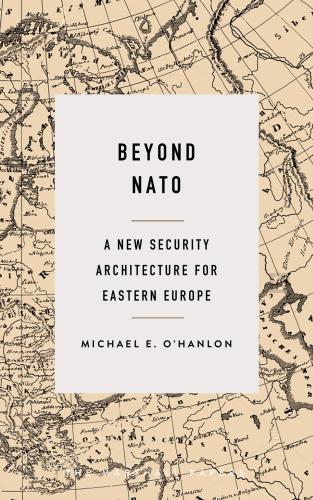

Michael E. O’Hanlon (@MichaelEOHanlon)

Michael E. O’Hanlon (@MichaelEOHanlon)

Senior Fellow and Director, Center for Security, Strategy, and Technology

NATO cannot give in to Russian bullying or allow Russia a sphere of influence over its formerly subjugated neighbors. Putin’s demands about Ukraine and eastern Europe are unacceptable as stated.

But we need to develop new concepts for future European security. Ukraine and Georgia should not be in NATO — even if Moscow should not be able to make that decision for them.

The core concept for future European security in eastern Europe would be one of permanent neutrality for former Soviet republics that are not now in NATO or the Russia-led CSTO. They should retain their sovereign rights to join any other international organization.

However, security alliances should not be used by Washington and Brussels as democracy promotion tools or instruments to advance the “European project.” They represent solemn promises to treat another’s territory as our own, and send American troops to fight and die in defense of allies, if needed. As the North Atlantic Treaty’s Article 10 underscores, alliance enlargement should not happen unless we genuinely believe it would contribute to a more stable Europe.

The new security architecture must require that Russia withdraw its troops from Ukraine and Georgia (and Moldova, most likely) in a verifiable manner. The Crimea issue would have to be finessed, since Moscow almost certainly will not give that strategic peninsula on the Black Sea back to Ukraine. After that occurred, corresponding sanctions that have been imposed on Russia due to its aggressions against neighbors could be lifted, though “snapback” provisions would remain in case Russia subsequently violated its promises.

Steven Pifer (@steven_pifer)

Steven Pifer (@steven_pifer)

Nonresident Senior Fellow, Center for Security, Strategy, and Technology and Center on the United States and Europe

Moscow has manufactured a crisis by deploying large military forces near Ukraine and has demanded security guarantees in its draft U.S.-Russia and NATO-Russia agreements. Many provisions in those drafts are unacceptable to Washington and NATO, while others offer a basis for discussion and perhaps negotiation. The big question: Does the Kremlin intend its draft agreements as an opening bid in a serious give-and-take negotiation, or does it seek rejection, which it would add to its list of grievances to justify a military assault on Ukraine?

U.S. and Russian officials met Monday and described their talks as serious. However, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Ryabkov stressed Moscow’s demand that NATO foreswear further enlargement and rule out Ukraine and Georgia ever joining. U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman termed that a “non-starter” but saw possibilities to address issues such as missiles in Europe and constraints on military exercises. Ryabkov left the door open for dialogue. There will be a NATO-Russia meeting tomorrow, and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe meets on Thursday.

NATO should engage Russia on its concerns regarding military activities, provided that Moscow addresses the concerns others have about Russian activities on a reciprocal basis. But it is not legitimate for the Kremlin to seek a veto over NATO enlargement or Kyiv’s foreign policy. While remaining ready to talk, the West should reiterate that Russian military action against Ukraine would lead to painful costs and consequences.

It will then be up to Vladimir Putin to decide how to answer the big question.

Melanie W. Sisson (@MWSBrookingsFP)

Melanie W. Sisson (@MWSBrookingsFP)

Fellow, Center for Security, Strategy, and Technology

If Putin invades Ukraine, it will not be because the Biden administration’s strategy is bad. To the contrary, the administration has done well to make clear the costs Russia will face as a result of aggression. It was wise, moreover, for Biden to establish early that the United States will not commit ground troops either to blunt or to eject Russia should it invade — the interests at stake do not justify direct U.S. involvement.

In the weeks leading into negotiations there has been much preoccupation with what it is that Putin wants. With few exceptions, there has been very little open discussion of what it is that Washington wants, other than Russian forbearance from invading Ukraine.

A negotiating position that requires Russia to do more than simply retrench from Ukraine, and that offers concessions in return, will indicate that the U.S. and NATO agree with Putin that the European security architecture needs revision. If the U.S. and NATO have no such demands for revision, however, they should be unwilling to make any concessions at all. In that case, a Russian invasion will accurately reflect the two sides’ relative satisfaction with the current order. So long as the U.S. and its allies hold firm and impose the threatened costs, they will be demonstrating their belief that the primary tenets of European security are sound. If that is indeed the administration’s position, then its deterrent strategy doesn’t have to work in order to succeed.

Constanze Stelzenmüller (@ConStelz)

Constanze Stelzenmüller (@ConStelz)

Senior Fellow, Center on the United States and Europe

Sunday marked the beginning of a week of negotiations that could prove decisive for the European security order and the trans-Atlantic alliance. After the Kremlin’s two “treaty drafts,” it is clear that for Russia, the goal is to reestablish dominion in eastern Europe, and push the U.S. out of Europe — effectively ending NATO. Russia threatens to use military force against Ukraine in order to achieve this much greater strategic goal.

The alliance response ought to be correspondingly clear and forceful. Specifically, it should state clearly what the West wants from Russia. A start would be: that there will be no further discussions unless Russia moves back its troops to a determined line — say 100 kilometers from the Ukrainian border.

Here are three more things the alliance could and should do:

- A declaration of first principles: NATO will not succumb to military threats for political goals; territorial borders are inviolable; countries are free to choose their own alliances. (And remind the Russians, who like to brandish treaties, of exactly where and when they signed on to these principles.)

- Counter disinformation about alliance disunity by regularly publishing statistics about U.S.-European consultations.

- Establish a cross-alliance task force to map out the prospective relative impact of Western economic sanctions on individual alliance members and discuss potential instruments to mitigate blowback.

Angela Stent (@AngelaStent)

Angela Stent (@AngelaStent)

Nonresident Senior Fellow, Center on the United States and Europe

If the U.S. went into the Geneva talks hoping to ascertain whether Russia is serious about negotiating about Euro-Atlantic security issues or merely using what it will claim are failed negotiations to justify another military incursion into Ukraine, then it did not receive an answer. Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Ryabkov agreed to continue negotiating but also said that a guarantee that NATO would not expand further was non-negotiable for the Russians — just as foreclosing NATO enlargement is a non-starter for the Americans.

It is not clear why Putin manufactured the crisis on the Ukrainian border at this particular time — he has been making many of his complaints about the U.S. and NATO since his Munich speech in 2007 — but he clearly senses this is an opportune time with the U.S. distracted by COVID-19 and its dysfunctional political system and key European players focusing their attention elsewhere. The deployment of Russian troops in Kazakhstan at the request of its beleaguered president strengthens Putin’s hand and reinforces his claim that Russia’s neighbors want to be in the Russian sphere of influence.

Putin’s goal is a wholesale relitigating of the post-Cold War settlement in Europe, hoping that the U.S. will withdraw and focus on its own domestic troubles. Where do we go from here? Best case: revived negotiations on the now-defunct Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty and the Conventional Armed Forces in Europe Treaty. Worst case? Another military incursion into Ukraine followed by punitive sanctions on Russia which will also adversely affect Western economies.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Around the halls: Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and the European security order

January 11, 2022