President Obama will make what is likely to be his last trip to sub-Saharan Africa while in office when he visits Kenya and Ethiopia later this week, just after hosting newly elected Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari at the White House on Monday. After what some have called a “slow start” (associated in part with the 2008 financial crisis), the Obama administration has initiated a formidable list of new U.S. government programs in sub-Saharan Africa, with a high point reached last summer when the president convened the first-ever U.S. Africa Leaders Summit. A defining feature of all the Obama administration’s activities in Africa has been the great emphasis the president has placed on improving the U.S.-African commercial relationship and supporting broader inclusive economic growth throughout the region. Each of his signature programs have consistently included a prominent role for the business community, with Power Africa reportedly leveraging an astounding $20 billion in commitments from the private sector to support badly needed electricity generation and access in the region.

In many ways, all these efforts began when the White House formally published the U.S. Strategy Toward Sub-Saharan Africa in 2012, a unique document that sets out key policy areas to guide all U.S. government efforts in the region. Not surprisingly, improved economic growth, business, and trade are featured prominently throughout the strategy, with five specific “actions” identified as primary goals for U.S. federal agencies (see text box). The president’s departure for Kenya and Ethiopia later this week offers an important opportunity to assess where African countries have progressed on these Obama administration goals during the president’s two terms in office. A quick review of relevant indicators reveals that progress has been mixed, so presenting this data might also help both African and U.S. policymakers use this moment to address areas in need of attention and leverage successes to date.

In many ways, all these efforts began when the White House formally published the U.S. Strategy Toward Sub-Saharan Africa in 2012, a unique document that sets out key policy areas to guide all U.S. government efforts in the region. Not surprisingly, improved economic growth, business, and trade are featured prominently throughout the strategy, with five specific “actions” identified as primary goals for U.S. federal agencies (see text box). The president’s departure for Kenya and Ethiopia later this week offers an important opportunity to assess where African countries have progressed on these Obama administration goals during the president’s two terms in office. A quick review of relevant indicators reveals that progress has been mixed, so presenting this data might also help both African and U.S. policymakers use this moment to address areas in need of attention and leverage successes to date.

First, though, it should be acknowledged that assessing this type of information is a challenging task. Movement against each of the U.S. government’s strategic focus areas depends on complex “push” and “pull” factors. External (or “push”) factors include the president’s initiatives, but also involve trends far outside his control, like the evolution of commodity prices. In contrast, “pull” factors are domestic variables, which are under the control of African policymakers and to some extent the business community and civil society in the region. These internal dynamics include time-intensive regional efforts to improve macroeconomic and political governance, as well as African initiatives to support competitiveness and economic transformation, among others. Ultimately, Africans are the ones that have to implement initiatives to support growth whether they are backed by the U.S. or homegrown.

1. Promote an enabling environment for trade and investment

Better policies to enable business and trade could support growth and promote an expansion in the benefits of the region’s economies. Accordingly, the Obama administration has committed to encouraging “…legal, regulatory, institutional reforms that contribute to an environment that enables greater trade and investment in sub-Saharan Africa.” The White House further states that this focus builds in U.S. participation in programs like the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative and the Open Government Partnership. Many sub-Saharan African countries have also prioritized creating an enabling environment for trade and investment ; however, the Heritage Foundation, in their annual index on “economic freedom,” which includes 10 measures of regulatory, fiscal, and rule of law restrictions, reports that the region hosts nine of the world’s 26 “repressed economies.”

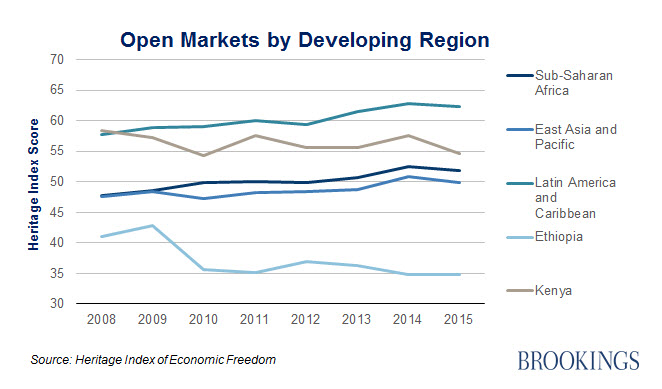

When measured by a subset of Heritage’s freedom ranking on “open markets” (trade, investment, and financial freedom), sub-Saharan African countries have been fairly static throughout Obama’s terms in office, but have recorded some modest progress. On Heritage’s scale of 0-100, sub-Saharan African countries on average have improved their score from 47 to 51 since 2008, an increase of approximately 9 percent. Big gains do not really register in other regions around the world either, though, with East Asia and the Pacific having a percentage increase of 5 percent and Latin America at 8 percent. In the below graph, we also highlight the president’s destinations of Ethiopia and Kenya, who respectively come in far below and moderately above the regional average, respectively.

2. Improve economic governance

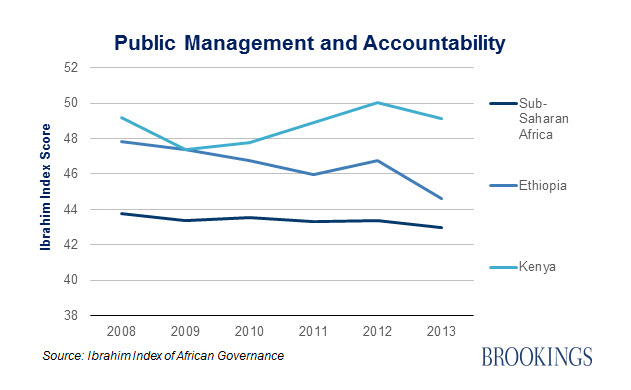

Somewhat relatedly, the president’s strategy on U.S.-Africa relations also identifies “…strong public financial management” as a key means to “…increase transparency and effectiveness in government operations and broaden the revenue base.” Several U.S. programs for engaging sub-Saharan Africa emphasize these areas, including the Millennium Challenge Corporation’s government effectiveness focus as well as the work of the U.S. Treasury’s Office of African Nations. However, the latest version of the Mo Ibrahim Foundation’s Index of African Governance notes that scores around “sustainable economic opportunity” have generally “stalled,” and a review of a subset of their data ranking African countries on “public management and accountability” shows a similar middling performance. As seen below, Ethiopia and Kenya score better than the regional average but are trending slightly downward.

3. Promote regional integration

African countries have historically traded with each other far less frequently than their counterparts in other regional groupings like Latin America and Western Europe. Acknowledging this deficiency, President Obama has prioritized supporting greater regional integration in Africa, highlighting intra-African harmonization as a key point in his strategy toward the region and backing that up with new programs like Trade Africa, which aims to increase coordination between countries in East Africa. This emphasis is consistent with the great priority African leaders have also placed on these issues, with 26 nations committing just last month to a new Tripartite Free Trade Area, a critical stepping stone toward the ambitious goal of creating a Africa-wide economic community by 2017.

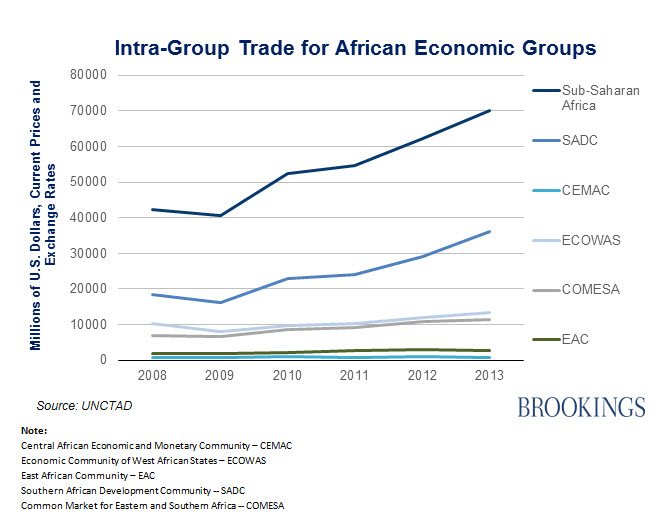

These policy commitments might have started to make a difference, as there have been big increases in intra-African trade during the president’s terms in office. Trade within sub-Saharan Africa has increased by 66 percent since 2008, and trade within the regional group the Southern African Development Community (SADC) has increased by 95 percent. Africa’s other major regional economic communities (also listed below) mostly show some gains too. (It should also be noted that these are “official” figures—if informal trade were included, growth in this area might be even higher!) Additionally, trade data in sub-Saharan Africa can be unreliable, so changes require some healthy skepticism. The president’s destinations of Kenya and Ethiopia are members of the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), and Kenya also plays a leading role in the East African Community (EAC). Both these groups plan to join the Tripartite Free Trade Area.

4. Expand African capacity to effectively access and benefit from global markets

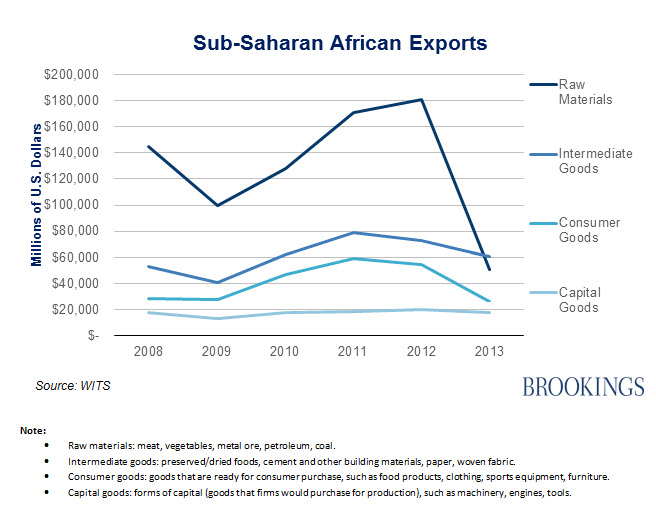

In addition to intra-regional trade, the Obama administration has also initiated efforts to support improved African capacity to engage with the international markets. Perhaps most significantly, last month the president signed the renewal of the African Growth and Opportunity Act, which provides eligible African countries with preferred access to U.S. markets and serves as a lynchpin behind broader U.S. efforts to support trade capacity building and expanded market access for African countries around the world. However, this important milestone comes at an incredibly turbulent time for African exporters, who historically have relied predominantly on the sale of raw materials, like unprocessed oil and gas. Dramatic recent fluctuations in the prices of commodities have prompted associated decreases in Africa’s international exports. President Obama’s strategy also seeks to support a “… diversification of exports beyond natural resources.” Raw materials exports have decreased by 65 percent since 2008, while intermediate goods (those that involve some processing) have seen a 14 percent increase in the same time period.

5. Encourage U.S. companies to trade with and invest in Africa

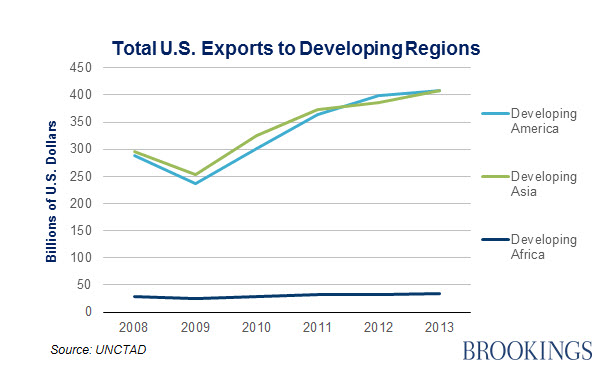

Helping U.S. businesses identify and pursue opportunities to trade with and invest in sub-Saharan Africa has been a key focus on the Obama administration. This area is also one where the president has perhaps the greatest potential to positively influence growth, given his control over the many federal agencies mandated to support American commerce. In this regard, the U.S. Strategy Toward Sub-Saharan Africa announced an entire “Doing Business in Africa Campaign” where the Commerce Department leads 11 U.S. agencies and a private sector panel in efforts to “connect American business with African partners.” These initiatives do correspond to increases in U.S. exports to Africa, but there is still significant room for improvement: There has been a 22 percent increase in U.S. exports to “Developing Africa” since 2008, but a 42 percent increase in exports to “Developing America” and a 38 percent increase to “Developing Asia.”

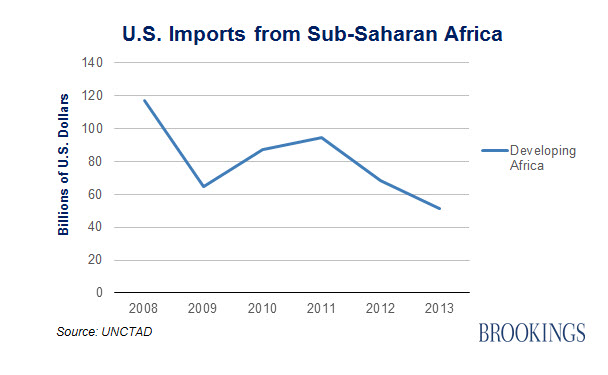

Unfortunately, African imports to the U.S.—still largely concentrated in commodities—have seen sharp declines as the American domestic energy production capacity has advanced.

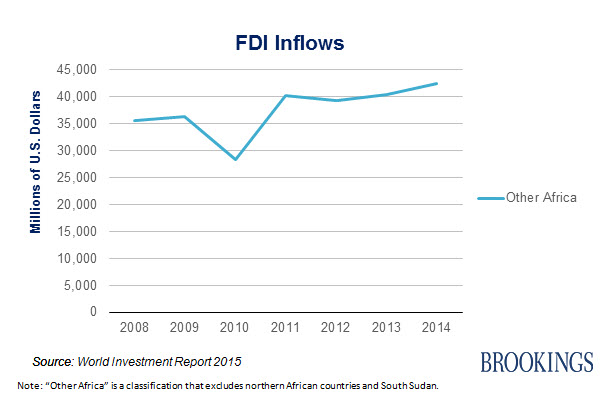

FDI inflows to sub-Saharan African countries have been more positive, with a 19 percent increase since 2008. Amadou Sy’s recent report, “Private capital flows, official development assistance, and remittances to Africa: Who gets what?” looks at the data starting in the 1990 and finds a positive trend as well.

When it comes to “greenfield” FDI trends (also known as FDI entering the region to support new investment projects), the U.S. stands out. The 2015 Ernst & Young Africa Attractiveness Survey reports that American companies were the largest source of greenfield investment in Africa in 2014. Since 2007, American businesses have initiated over 700 FDI projects in Africa, “pouring in US$52.7b and creating nearly 98,000 jobs.” This is a significant standout area for the president’s goals.

Conclusion: An unfinished agenda

Movement around each of these areas is mixed and inconsistent. This is understandable given that the Obama administration’s goals really cannot be assessed in a unified way—the institutional change required to support improvements in public financial management is a slow and daunting challenge, whereas the technological breakthroughs, like those in the area of hydraulic fracturing, for example, can alter a business calculus relatively overnight. Rather than a showing lack of progress, perhaps the mixed results of this quick exercise indicate that attempting to improve progress on each of these items should be a source of consistent attention, and reviewing the data can be a helpful guide to areas in need of special focus. It also seems many U.S. programs are positioned to support positive change around areas of slow progress. The president’s Power Africa initiative, for example, aims to create infrastructure improvements, which enable better business performance and could help increase trade, ultimately adding to advancements around measures of competitiveness. It would be tempting therefore to recommend a focus on implementation of this initiative, Trade Africa, and the many other U.S. government programs during the president’s last 18 months in office. However, working on project implementation must occur as the president also focuses on the broader underpinnings of his goals on economic growth in Africa. The lynchpin of many of President Obama’s key Africa initiatives—the U.S. Export-Import Bank—was allowed to expire last month, and the battle to renew its authorization will require concreted efforts on Capitol Hill. Moreover, after some precarious maneuvering toward the end of the process, the African Growth and Opportunity Act was renewed last month. While this is an important milestone, however, much can still be done to strengthen the program and important proposals could be pursued to consolidate gains.

Commentary

An unfinished agenda: The progress of U.S.-backed economic development goals in Africa

July 20, 2015