Content from the Brookings Doha Center is now archived. In September 2021, after 14 years of impactful partnership, Brookings and the Brookings Doha Center announced that they were ending their affiliation. The Brookings Doha Center is now the Middle East Council on Global Affairs, a separate public policy institution based in Qatar.

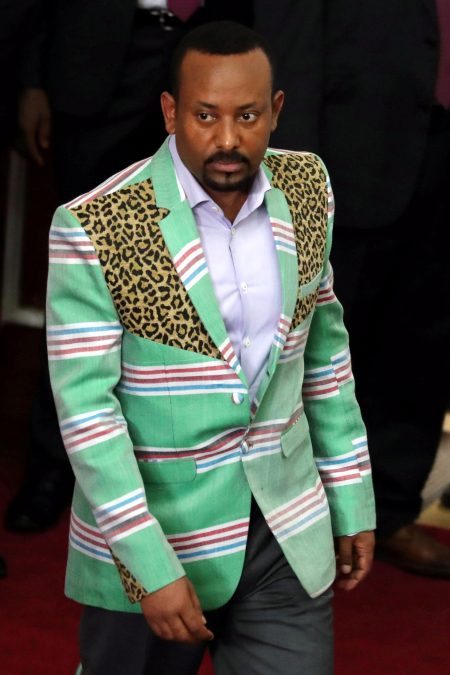

Abiy Ahmed has been awarded this year’s Nobel Peace Prize. Never heard of him? You aren’t the only one. Official Washington has paid little attention to the extraordinary transition that began last year in Ethiopia under the new prime minster’s tutelage. The man in the eye-popping blazers — think sea foam green with pink stripes and leopard print inlays — began his tenure with equal flair: He lifted the long-repressed nation’s state of emergency, released thousands of political prisoners, halted media censorship, and appointed women to top posts. Winning international praise at each turn, he also ended two decades of frozen conflict with neighboring Eritrea — the act for which his prize was nominally bestowed.

But the Nobel Committee’s announcement is also a call for attention: Abiy has finally taken the lid off Ethiopia, initiating one of the world’s most important political transitions, but also its most fragile.

Well aware of the challenges Abiy and his 110 million constituents face, and the problems already manifest, the committee’s announcement cited concern about growing “ethnic strife” and the social unrest that in recent years has displaced some three million people — more than anywhere else in the world. “No doubt some people will think this year’s prize is being awarded too early” they noted in pre-emptory fashion. But the committee believes “it is now” that the prime minister’s efforts “deserve recognition” and “need encouragement.” They’re right on both counts.

Among Ethiopians (and many foreign observers), opinions of the 43-year old prime minister are as diverse as they are passionate. Supporters refer to him, not infrequently, as a “gift from god,” hailing his divinely inspired agenda and his rhetoric of unity and reconciliation. Critics balk at what’s become known as “Abiy-mania,” however, variously concerned that the Pentecostal preacher-in-chief is naïve, self-aggrandizing, or an unconvincing product of the old guard. (Abiy is a member of the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front, or EPRDF, which has ruled the country since 1991 and is known for its abuses of democracy and the security and intelligence establishment from whence he came.)

Whatever one thinks of Abiy, he deserves genuine credit for ending a senseless stalemate with Eritrea, and for the gusto with which he has pledged to usher in an era of openness, modernity, and economic liberalization at home. Even prominent skeptics agree. After unprecedented protests gripped the nation in 2018, and in turn paved Abiy’s unlikely path to the top, one former regime figure told me that while he did not believe Abiy was the “right doctor for Ethiopia’s long-term care,” he may be the “emergency room medic we need” right now.

The prestigious recognition, while deserved, must be accompanied by a sober appreciation of what came before Abiy, and of the bumpy road ahead. The ruling EPRDF is a marriage of convenience, a four-tentacled coalition that allowed each ethno-regional arm a degree of autonomy and a share of the national cake. While famously disciplined and undeniably heavy-handed, proponents of the liberation movement-turned ruling party argued their formula is what has held one of Africa’s largest and most diverse countries together for three decades.

At the center of the coalition was the Tigrayan Peoples’ Liberation Front (TPLF) — a minority from the country’s northern highlands that dominated the regime’s political and security structures until the passing of its intellectual strongman, Meles Zenawi, in 2012. Abiy isn’t one of them, and his ascension in 2018 was a watershed moment. The outgoing TPLF — unaccustomed to anything but total control — was thus believed to be the greatest threat to Abiy’s rule and his plan to overhaul the state they fashioned.

The new leader’s declaration of peace with Eritrea was an historic and courageous act. More than 80,000 died on the battlefield between 1998-2000, and the two countries had been locked in a tense standoff ever since. When Abiy and his Eritrean counterpart personally opened the border crossings last fall, his office announced the “radical transformation” of the border into a “frontier of peace and friendship.” Citizens from both countries flooded across the boundary for the first time in 20 years. When the first flight between the two nations touched down in Eritrea’s capital city, families long divided by war embraced on the tarmac, tears streaming down their faces. Abiy’s opening to Eritrea was right on its merits. But it was also motivated by domestic politics.

Much of the war was fought in Tigrayan territory, near the border with Eritrea, and the hostility between the TPLF and Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki is hard to over-state. Abiy and Isaias thus shared an interest, as one seasoned observer noted, of “choking the life out of the TPLF.” Since Abiy’s arrival, TPLF bosses have left their privileged posts and returned home to Tigray — first to lick their wounds, and then to organize. And they aren’t alone — the powerful Amhara and Oromo constituencies have likewise reinvigorated their political cadres, their regional security forces, and their nationalist rhetoric. Some argue the EPRDF coalition will persist in one form or another, its inherent compromise too valuable to each constituent part. Others believe it is already dead.

National elections are slated for 2020. Some worry Abiy won’t be able to hold it together, much less to advance his sweeping domestic and regional agendas. (The border crossings to Eritrea have been closed again, and full implementation of the peace pact remains an aspiration.) Others fear that when the going gets tough, Abiy may resort to an all-too familiar playbook of repression. As such, the Nobel Committee is also hoping this year’s prize can both encourage its recipient to stay the course and act as a guardrail as his government enters a period of profound political uncertainty.

This is not the first time Alfred Nobel’s trustees have sought to maximize the award’s political potential, or the first time its recipient has proven controversial. Aung San Suu Kyi, then a Burmese opposition figure, received the prize in 1991 for championing human rights and a “democratic society in which [her] country’s ethnic groups could cooperate in harmony.” She was later elected to the country’s top political post, and like Abiy, won great international acclaim. But when her government was accused of killings, human rights violations, and ethnic cleansing last year, many called for the Nobel committee to take back her prize.

Abiy Ahmed was right; the time for change in Ethiopia had come. Now he must balance tradition and modernity, democratization and stability, ethnic loyalties and national identity. The success or failure of Abiy’s high wire act will shape not only his country, but the entire region, for a generation to come.

When I asked another of the prime minister’s skeptics what he thought of last week’s Nobel announcement, he opted not for the usual cynicism, but for the spirit of unity Abiy has championed. “I am celebrating,” he said, “after all, this is the first Ethiopian ever to win the prize.” Here’s to hoping that all Ethiopians can celebrate Abiy’s prize for a generation to come, and that no one ever has to ask for it back.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Alfred Nobel catches ‘Abiy-mania’

Praise and caution for Ethiopia's prize winner

October 15, 2019