The U.S. drone strike that killed al-Qaida leader Ayman al-Zawahri in Kabul last weekend jolted Americans, reminding them that Islamic extremists are still active, writes Daniel L. Byman. This op-ed originally appeared in the Los Angeles Times.

The U.S. drone strike that killed al-Qaida leader Ayman al-Zawahri in Kabul last weekend jolted Americans, reminding them that Islamic extremists are still active. The Russian invasion of Ukraine, the rise of China, climate change and the COVID pandemic are among the many pressing issues that have relegated foreign terrorism to the rearview mirror.

And yet, as President Biden pointed out, America’s national security apparatus never forgets. “No matter how long it takes, no matter where you hide,” he said Monday night, “if you are a threat to our people, the United States will find you and take you out.”

But how much of a threat was Zawahri? Will his death protect Americans?

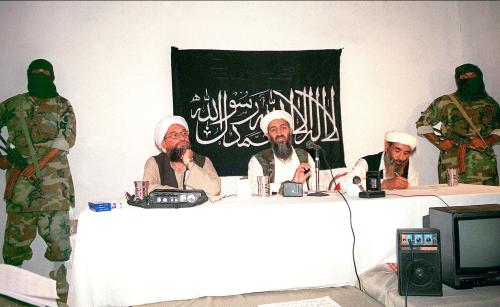

As much as the success of the manhunt demonstrates necessary resolve against terrorists who attack the U.S., the al-Qaida that Zawahri left behind was already diminished by internal and external forces. Since Osama bin Laden’s death at U.S. hands in 2011, and since 9/11 itself, it’s been a shadow of the organization that once commanded world attention. A new leader might revive its fortunes somewhat, but al-Qaida’s threat to the U.S. homeland will remain limited.

Drone strikes, a global intelligence campaign and better homeland defenses all have taken a substantial toll on the group, as did infighting within the radical Islamist movement and the atrocities its adherents inflicted on Muslim civilians in Iraq and other countries. Key planners, fundraisers, trainers and other lieutenants were killed, arrested, or forced to lie low, making it hard to plot spectacular attacks or even maintain a coherent movement.

Al-Qaida proper has not successfully attacked the United States or Europe since 2005, an eternity for a terrorist group seeking to grab world attention. Rival but related organizations such as Islamic State, commonly known as ISIS, have also been undermined by concerted counterterrorism efforts and infighting. ISIS’ loss of territorial control in Iraq and Syria was a crippling blow for a group whose brand centered on creating a genuine caliphate ruled by Islamic law.

Under the uncharismatic Zawahri, al-Qaida survived but it didn’t thrive. He was unable to stop ISIS from violently rejecting his leadership and proved uninspiring to many potential recruits. Bin Laden’s No. 2 could claim one gain during his tenure, the group’s expansion, often through converting terrorist groups in the Middle East, Africa and South Asia into al-Qaida affiliates.

Some of these offshoots — notably the Yemen branch, known as al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula — have inspired and perhaps even orchestrated attacks on the West, including the most recent attack in the United States, in Florida in December 2019. The attacker, a Saudi military trainee, killed three and wounded eight others at a naval base before he was killed. According to FBI Director Christopher A. Wray, the trainee was “more than inspired” by al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula, he “was sharing plans and tactics” with it.

Most of the other affiliate groups, however, are focused on civil wars and other local concerns. They threaten regional stability but are less of a danger to the U.S. AQAP, whose leader was killed in a U.S. drone strike within months of the Florida attack, is said to be splintering.

Lone wolf attacks like the Boston Marathon bombing, where self-radicalized individuals act without direction from an organization, remain a worry, but the perpetrators tend to be less trained and thus less lethal.

Afghanistan under the Taliban is a different concern, highlighted by Zawahri’s having taken refuge in Kabul, and the terrorist presence there should remain an intelligence priority. Still, it does not follow that a more pragmatic Taliban, which is seeking Western aid and funding, will allow Afghanistan to become a base for training camps and recruits, as it was in the 1990s. In addition, the Zawahri strike shows that U.S. counterterrorism efforts, despite the American exodus in 2021, can still be devastatingly effective.

Much depends on the next generation of Islamic radicals. A new al-Qaida or ISIS leader seeking to re-energize his movement might try to attract donors and recruits by conducting high-profile operations in the West.

Continued counterterrorism efforts, however, make another 9/11 or an attack such as Paris in 2015 difficult — one reason al-Qaida turned to the local campaigns of its affiliates in the first place. It isn’t easy to command a movement when your organization is under siege. ISIS is a case in point. It has foundered under a series of unimpressive leaders, all of whom spent more time hiding than they did directing their followers.

Finally, the threat posed by al-Qaida and its ilk will depend on whether a new cause makes them urgently relevant again. The U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 electrified the Muslim world and vindicated al-Qaida’s argument that the United States was bent on regional domination. After 2011, the Syrian civil war and the caliphate ISIS declared in 2014 led to huge surges globally in recruitment and support for Islamic militants.

Today, civil wars in Yemen, Somalia and the Maghreb engage local fighters but have limited motivational appeal globally. Without another galvanizing Iraq or Syria, al-Qaida and like-minded groups may fade even further into yesterday’s news.

Commentary

Op-edAl-Qaida lost its leader, but are Americans any safer?

August 5, 2022