Academics and policymakers are actively looking at creative ways to help college students succeed. While increasing college access and enrollment is an important first stage, too many students matriculate but fail to thrive. Bluntly, too many never graduate.

Like most faculty, I have many informal “advising conversations” with undergraduates. I like to think these conversations do some good. I’d never thought much about whether formal advising systems do much and whether they can contribute to overall student success. But there is now some solid evidence that good advising makes a real difference.

Authors Serena Canaan, Antoine Deeb, and Pierre Mouganie offer a very nice piece of work in “Advisor Value-Added and Student Outcomes: Evidence from Randomly Assigned College Advisors.” (In the interest of full disclosure, I like to brag about have a slight conflict of interest regarding two of the authors: Canaan is a UCSB alumna and I’m currently a member of Deeb’s dissertation committee.) The authors use data from a natural experiment at one university to show that good advising can really matter.

First, a little background about college advising offers some context. About half of U.S. colleges have freshman advised by full-time faculty, accounting for more than three-quarters of all new undergraduates. Interestingly, the use of faculty as advisers varies among type of institutions. Most baccalaureate-granting institutions use faculty, but research universities tend to have a professional advising staff. (Faculty serve as official advisers at only about a fifth of research universities.)

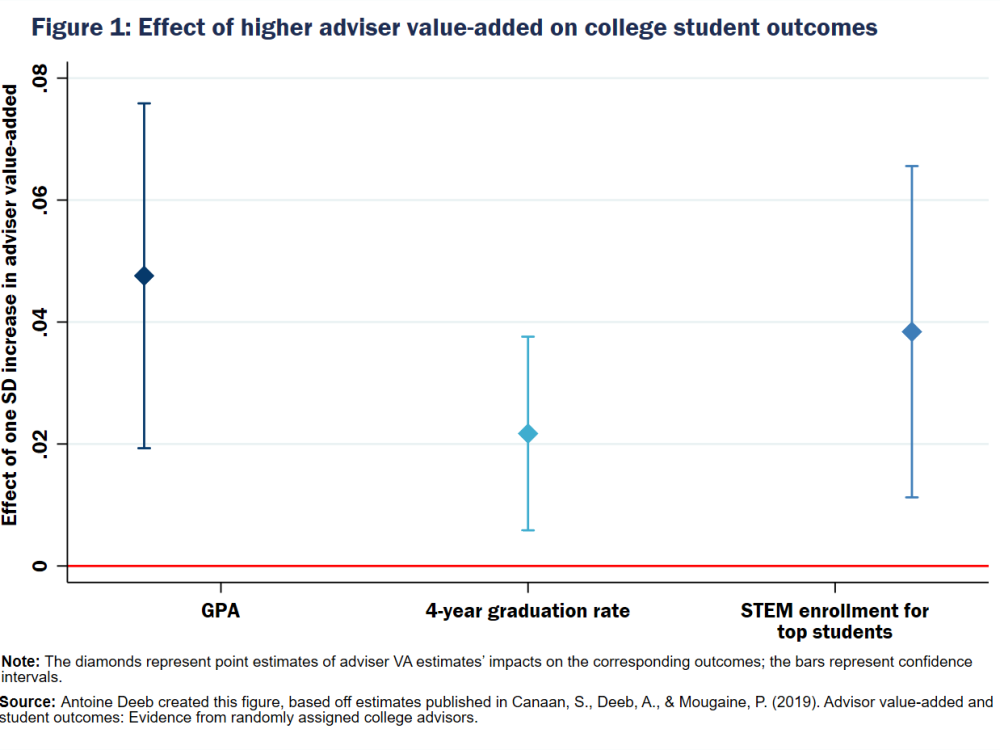

Before looking at the papers’ details, here are some of the headline results (see Figure 1 below). A one standard deviation increase in the estimated value-added of the freshman-year adviser:

- Increases freshman GPA by 5.7 percent of a standard deviation.

- Increases 4-year graduation rates by 2.5 percentage points.

- Increases the probability of high-ability students enrolling in and graduating from a STEM major by 4 percentage points.

These effects of having a good adviser are meaningful; not huge, but remarkable considering the relatively few interactions that most advisers have with undergraduates.

What makes these estimates so convincing is that the data comes from a natural experiment that eliminates a common weakness seen in many value-added studies. The data is sourced from a university in which students are randomly assigned to advisers; thus, the estimated relationship here is causal, which is a high bar for most other studies to clear. (The administrative assignment process is intentionally random, and the authors ran statistical checks that show the randomization worked.) In most studies of student outcomes, we worry that we are missing some unobservable factor that is correlated with what we’re studying; a teacher having a class in which more parents than usual buy outside tutoring for their child would be an example that could compromise estimates. Random assignment eliminates such concerns.

The university involved in the study was the American University of Beirut (AUB), which raises a question of what scientists call “external validity;” in other words, do we think the results are relevant to the typical American college? The answer is “yes.” A little background about AUB explains why. AUB was founded by American missionaries in 1866. Classes are taught in English and AUB degrees are registered with the New York State Board of Regents. Enrollment is around 7,000 students and admissions depend mostly on SATs and grades—average SAT scores look a lot like average American SAT scores. As the authors put it, “AUB is comparable to an average private nonprofit 4-year college in the United States.”

The results cited above demonstrate that, on average, good advising is valuable. The researchers then delve deeper and find is that the results are heterogeneous—having a good adviser is more important for some students than for others and who benefits most is situational. Improvements in freshman-year GPA are larger for high-ability students than for low-ability students, though both groups gain. There is not a noticeable difference by student gender.

Also, top advisers are more likely than others to guide their students into selective majors (STEM and business). This is especially true for high-ability students, defined as students entering with SAT scores in the top quartile. It appears that these results reflect pointing top students to STEM majors and a smaller effect for students being pointed to business, where the increase in entering a business major is also true for students with lower SAT scores.

The authors investigate the mechanism for the various improvements. What they tease out from the data suggests that freshman-year advisers are particularly good at helping students get good freshman-year grades. (By the way, good advisers don’t steer students into easy courses—the authors checked.) These higher grades likely increase student confidence, leading to better performance later on, and directly increase the chances of making it into a selective major.

Improving college student achievement and graduation rates has become a major concern. In the U.S., only about a third of college students complete their four-year degree within four years at public institutions, and about half do so at private nonprofits. The results from this study suggest that more or better faculty advising might be a promising avenue to improve these numbers, although it’s obviously important to ask where the needed resources will come from. It’s worth noting in this regard that AUB had a student/faculty ratio of 11, while the U.S. ratios are about 15.5 at public institutions and 10.2 at private nonprofits. Arranging more and better faculty advising would be beneficial, as this study shows, but would be especially challenging at large public universities. In light of the numbers above showing that large universities rely on staff rather than faculty for advising, it’s worth remembering that the authors of this study don’t make comparisons between faculty and staff as advisers. So, while we’ve learned that having a good faculty adviser makes a big difference, more research will be needed to know if having a good staff adviser would have the same effect.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).