A few weeks ago, the Trump administration unveiled a framework to support a much-needed rebuild of the nation’s infrastructure. As our Brookings Metro colleagues have observed, the proposal leans heavily on governments outside Washington to foot the bill. The proposed Infrastructure Incentives Program would offer $100 billion for investment in a wide range of infrastructure types, but cap the federal contribution to projects at 20 percent, essentially rewarding states and localities that are able to raise new revenues or attract private capital.

This proposal poses a quandary for the Rust Belt: the region hosts some of the nation’s most aged and degraded infrastructure, but is also home to a large number of communities with little to no ability to pay for rehabilitating it. While the administration’s plan isn’t going anywhere anytime soon, it nonetheless exposes anew the fiscal and governance dilemmas that underlie infrastructure challenges in many of the region’s vulnerable communities.

Too much localism

The problem starts with the sheer number of local governments in Midwest states. The Northwest Ordinance adopted by Congress in 1787 organized the then-territories of the Midwest by codifying the values of Jeffersonian democracy: The region would have free labor, not slave labor. It placed value on education and schools. And it organized a political governance structure close to the people. The region was platted in 6-by-6 mile townships, each housing a school (and ultimately a school district). As frontier cities and towns grew, they were incorporated into numerous additional municipalities.

One result is that the states of the Midwest have more local governmental units than others. The region is home to seven of the top 10 states in total governmental units, and all save New York are well above the nation’s average for governmental units per capita (Table 1). My home state of Michigan has more than five times the number of local governments as Virginia (2,875 versus 518) with only a slightly larger population.

The number of local units is not the problem in and of itself. As Jefferson envisioned, there are benefits to elected officials knowing the residents they represent by name. Service delivery isn’t necessarily more expensive either—the cost of picking up the trash each week is about the same per household, whether you live in a city of 1 million or a village of 10,000.

But this fragmented landscape of numerous political decisionmaking bodies doesn’t serve the geography of an economy and society that has changed dramatically over the past 200 years. Interdependent municipalities in metropolitan regions benefit from, and even demand, regional organization of transportation services, infrastructure, planning and zoning, economic development, and job training, among many other functions. In the Rust Belt, highly localized interests frustrate coordinated regional action.

A vicious cycle

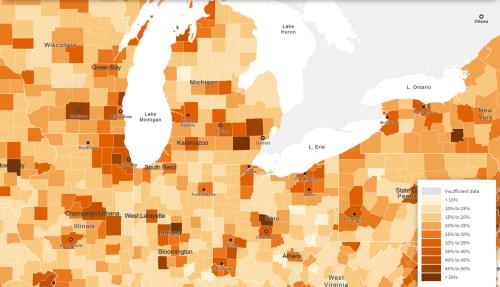

These challenges are mirrored in the region’s strained local fiscal capacity. As the Trump administration and Congress consider proposals that could ask state and local governments for the lion’s share of resources to rebuild America’s infrastructure, state and local tax policies in Michigan and other Midwest states have not adapted to a changed economy and population. Many of their communities have lost residents, thus diminishing property values and tax bases, constraining local municipal revenue-raising opportunities, and reducing state revenue sharing. As a previous post explored, these dynamics go hand-in-hand with the region’s high levels of racial segregation. At the same time, these communities still bear the costs of maintaining existing infrastructure designed for larger populations, delivering services to remaining residents, and paying generous health and retiree benefits to municipal workers and retirees promised during the region’s economic salad days.

The Rust Belt’s local fiscal situation was already fragile when the Great Recession and auto collapse struck in 2008. Ten years later, property taxes—the largest source of revenue for local governments in the Midwest—are largely below their pre-recession peak. This is true for 85 percent of Michigan’s communities despite low unemployment and a recovered auto industry. According to a Michigan State Housing Development Authority review in 2017, there are nearly 200 Michigan cities, villages, and townships exhibiting economic distress. At any given time, about one in ten Michigan municipalities and school districts faces significant fiscal stress and mounting deficits.

Beyond Michigan, other Rust Belt states with similar governance structures and economic dynamics are pinched as well. A 2017 study by the Pennsylvania Economy League finds that overall municipal fiscal stress in Pennsylvania has accelerated over the past few decades. “The disturbing drift threatens the ability of all types of municipalities to provide even basic services that keep the communities where we live, work, shop and go to school safe, well-maintained, and free from crime and blight. It means core municipalities, whose fiscal health has a direct influence on the financial well-being of the surrounding region as centers of commerce, health care, courts, education and more, are increasingly distressed.”

It’s a vicious cycle for communities on the losing end of these changes. Population loss results in lower tax revenues. Less revenue means reduced services. Fewer services drive out more residents who, if nothing else, move a mile down the road to an adjacent community with better-funded schools, safety, and public works. Oftentimes, those who stay in the community remain on the hook to pay pensions and health care benefits for employees who moved away.

No help for Flint

We saw this movie recently—in Flint, Michigan. The water crisis sprang from Flint’s fiscal distress, itself brought about by deindustrialization starting in the 1980s. The city lost jobs—from a peak of 75,000 GM employees to fewer than 7,000 today—and corresponding population—from 200,000 residents in 1970 to under 100,000 today. The extreme reduction in the city’s tax base was compounded by a $60 million decline in state sales tax revenue sharing, tied in part to lost population and in part to the Michigan legislature’s whims (the statewide reduction to all Michigan municipalities was approximately $6 billion). The Great Recession reduced Flint’s property values to approximately half of their pre-recession levels, while increasing the demand for basic services, such as police and fire protection, as crime spiked and more properties were abandoned. The state responded in 2011 by passing new legislation that strengthened the governor’s ability to appoint emergency financial managers in municipalities who were charged with reducing expenditures. Flint’s emergency managers switched the city’s water source to the polluted Flint River to cut costs. Today, as Flint works to recover, it’s attempting to provide basic services with only half of the general funds it had as recently as 2000.

Relief from fiscal distress and the resources to rebuild infrastructure in Flint and many other Midwestern communities are not going to be found in a “flip-the-switch” proposal that requires locals to find most of the money. As my colleague Adie Tomer points out, the Trump administration’s framework would mean “the rich get richer”; more prosperous communities that can raise local resources would receive the federal incentive funding. Rust Belt communities that today can’t keep the grass mowed or the lights on—much less repair 75-year-old water mains—would be out of luck.

What has to happen? Even under the best circumstances, Midwestern communities would need the federal government to assume a higher share of the infrastructure finance burden. At the same time, Midwestern state and local governments will have to help themselves. They must reform their municipal finance systems to support older communities, including by consolidating or sharing wealth among local governmental units. That’s a fix so politically hard it has eluded all but a few attempts (see this recent example from Illinois, home to the most local governments in the nation by far). But short of these bolder moves, a true rebuild and revival of our Rust Belt communities will remain a chimera.

Former Flint Mayor Dayne Walling contributed to this blog post.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

A Rust Belt rebuild can’t rest on locals

The Trump infrastructure plan provides reminder that the region’s many local governments can’t self-finance their renewal

Monday, March 5, 2018