The January employment numbers, released today by the U.S. Department of Labor, present mixed evidence about the state of the labor market. While the unemployment rate dropped to 9 percent, payrolls were just better than flat, increasing by only 36,000 jobs last month.

Much attention is given to the official unemployment rate, which is certainly an important indicator of our employment situation. But, in fact, the unemployment rate tends to understate the severity of the challenge for American workers in the aftermath of the Great Recession. In this month’s posting, The Hamilton Project provides a more comprehensive look at the U.S. employment situation, focusing on a broader measure of the unemployed. In addition, we examine the impacts of education on unemployment and the widening gap between the least- and best-educated workers. Finally, we continue our focus on the “jobs gap,” or the number of jobs the economy needs in order to return to return to pre-recession employment levels while absorbing the 125,000 people who enter the labor force each month.

A Broader Look at the Employment Situation

The traditional unemployment rate does not fully capture the extent of labor underutilization in our economy. In addition to the 14 million Americans who are officially counted as unemployed (the jobless who are still actively looking for work), there are over 11 million Americans who either want to work but have given up looking, or who are underemployed in the sense that they are working part time because full-time work is unavailable. These additional workers are less visible but are undoubtedly victims of the recent recession.

Adding these additional unemployed and underemployed Americans to the standard measure of unemployment shows that a full 16 percent of the workforce in January 2011 is unemployed or underemployed.

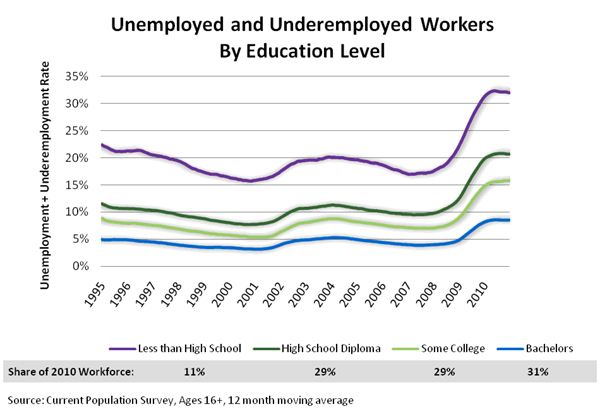

As the following chart shows, these unemployed and underemployed are disproportionately composed of less educated workers, reinforcing yet another benefit of educational investments.

The Importance of Education

One aspect of this chart is optimistic—the negative impacts of the Great Recession have begun to taper off and this broad measure of underemployment has begun to decline. With regard to education, however, the story is more startling. One in three people in the United States with less than a high school diploma is either unemployed or underemployed. Even earlier in the 2000s, nearly one in five was unemployed or underemployed.

Clearly, those Americans with a college degree have done significantly better in these tough economic times than those with a high school diploma or less—or even some college education. For those with high school diplomas, this broader rate of unemployment and underemployment grew by over ten percentage points (nearly 5 million workers), since the start of the Great Recession. In contrast, those with a college degree experienced less than a 5 percentage point increase (approximately 2 million workers), when we look at the broader rate of unemployment and underemployment. Beyond the immediate difficulties that unemployment causes for affected families, these differences in labor market participation undermine the country’s social fabric.

The January Job Gap

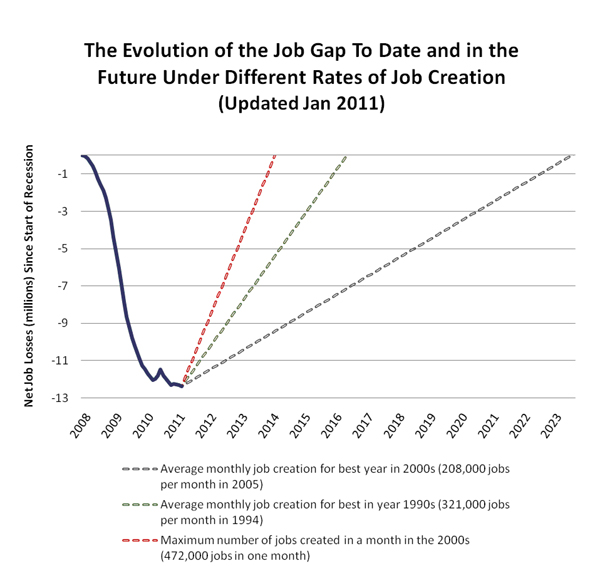

As in previous blog postings, The Hamilton Project explores the monthly “job gap” based on the employment numbers—or the number of jobs the economy needs in order to return to return to pre-recession employment levels while absorbing the 125,000 people who enter the labor force each month.

The annual revision to the historical payroll numbers released with the January report paint an even starker picture for the job gap this month, increasing it to 12.4 million jobs.

The chart below shows the evolution of the job gap since the start of the Great Recession in December 2007. The thick line in the chart below shows the net number of jobs lost since the Great Recession began.

The broken lines display the date by which the jobs gap would be closed under alternative assumptions about the rate of job creation going forward. If the economy adds about 208,000 jobs per month, the average monthly rate for the best year of job creation in the 2000s, then it will take until July 2023 to close the job gap. At a more optimistic rate of 321,000 jobs per month, the average monthly rate for the best year of the 1990s, the economy will reach pre-recession employment levels by May 2016.

The Challenges Ahead

Our economy’s most important resource is its labor force. With 16 percent of the U.S. workforce underemployed or unemployed, our economic recovery still has a lot of ground to cover.

This discussion also brings to light the importance of education in our economy. As the evidence clearly shows, more education improves your chances in the labor market, in good times and bad. At the same time we face the challenge of improving the preparedness of our labor force, state and local governments—which are largely responsible for public education—are responding to their challenging budget situations by cutting spending, and education spending has not been spared. The individual and societal benefits to education include reduced periods of unemployment and underemployment. It is important that states identify ways to solve their current budgets problems without compromising the futures of their youngest citizens.

At a February 25th event, The Hamilton Project will release papers and outline key principles for state and local governments as they grapple with growing budget deficits. Later this year, The Hamilton Project will host a conference that specifically focuses on ways to strengthen our K-12 education system.

In the meantime, The Hamilton Project has launched a new prize competition to generate new and innovative thinking about how to create jobs and enhance productivity for American workers. While we must focus on long-term investments, like education, this is an opportunity to highlight shorter-term solutions for creating jobs and putting unemployed Americans back to work.

Commentary

A Broader Look at the U.S. Employment Situation and the Importance of a Good Education

February 4, 2011