On the inaugural episode of Global India, host Tanvi Madan, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, speaks with two former Indian ambassadors to Beijing on Indian perceptions of China and New Delhi’s strategy toward its largest neighbor. Ambassador Vijay Gokhale and Ambassador Shivshankar Menon share their views on India-China competition, the potential for cooperation or crisis, and what it means for India’s partners.

- Listen to Global India on Apple, Spotify, and wherever you listen to podcasts.

- Watch on YouTube.

- Learn about other Brookings podcasts from the Brookings Podcast Network.

Transcript

-

03:24 The state of India-China relations 20 years ago

-

07:27 The relationship since 2008

-

11:45 The uneasy state of India-China ties today

-

14:17 What the India-China border dispute is about

-

18:23 Spring 2020 border clashes

-

23:34 Is India moving the goalposts on the border agreements?

-

27:32 A shift in Indian public opinion on China across the board

-

29:06 China’s changed posture on India’s periphery

-

32:52 Do India and China have a similar vision of the Indo-Pacific region?

-

35:26 What are the areas where India and China are still cooperating?

-

38:50 Four trends evident in India’s recent approach to China

-

41:05 Should India deepen ties with the U.S., or hold back?

-

43:03 India deepening ties across the region

-

46:31 What would détente between India and China require

-

49:20 What is the chance of crisis escalation between India and China?

-

51:26 Areas of potential competition and cooperation in the coming years?

-

54:11 Lightning Round: What is the biggest myth about India-China relations?

[music]

MADAN: Welcome to Global India, I’m Tanvi Madan a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, where I specialize in Indian foreign policy. In this new Brookings podcast, I’ll be turning the spotlight on India’s partnerships, its rivalries, and its role on the global stage. This season our conversations will be focused on India’s relationship with China, and why and how China-India ties are shaping New Delhi’s view of the world.

The reason this inaugural season is focusing on India’s relationship with China is because these days that is the prism through which policymakers in New Delhi often see and assess other countries and other issues. China is India’s largest neighbor; it is also India’s second largest trading partner. But it is also at the same time India’s primary external rival, one with whom India fought a war in 1962.

Those tensions have re-emerged in recent years, and they have significantly affected almost every aspect of Indian foreign policy. Moreover, what happens between India and China won’t just affect the two countries, but the region and arguably the whole world.

Our first episode will take a big picture look at the relationship between India and China. My guests are two former senior Indian officials, both of whom are China hands. Ambassador Shivshankar Menon is a distinguished fellow at the Center for Social and Economic Progress in New Delhi. He was India’s national security adviser from 2010 to 2014. Before that he served as foreign secretary—that is, the senior most bureaucratic position in India’s Foreign Ministry. He was also India’s ambassador to China between 2000 to 2003.

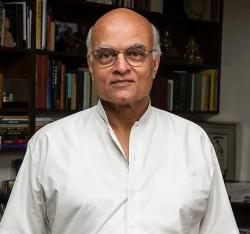

We’re also joined by another former ambassador to China, Ambassador Vijay Gokhale, who led India’s mission in Beijing between 2016 and 2017. Following that he served as Indian foreign secretary from 2018 to 2020. Now he is a nonresident senior fellow at Carnegie India.

Both my guests are prolific writers and have authored several books that are worth reading. We link to their bios in the episode notes. Here I’ll mention Vijay Gokhale’s book The Long Game: How the Chinese Negotiate with India, and Shivshankar Menon’s Choices: Inside the Making of India’s Foreign Policy.

In this conversation recorded before the G-20 Summit as well as before the BRICS Summit, the two former officials explained where the India-China relationship stood 15 years ago, where it stands today, and what changed. My guests also discussed the concerns that India has about China and New Delhi’s strategy for dealing with that country. Our conversation also covered the prospects for a Indian-China rapprochement or cooperation, or for that matter crisis escalation.

[music]

And of course, we talked about implications of relations between these two Asian giants for other countries, particularly the United States.

Welcome to the Global India podcast, Ambassador Shivshankar Menon.

MENON: Thank you. Thanks for having me.

MADAN: Ambassador Vijay Gokhale, welcome to this inaugural episode as well.

GOKHALE: Thank you, Tanvi.

3:24 The state of India-China relations 20 years ago

MADAN: I want to start this conversation by taking us a few years back, not as far back as the ‘40s, ‘50s, or ‘60s, but about 15, 20 years back. If we had been having this conversation, Ambassador Menon, starting with you, just in in brief, how would you have described 15, 20 years ago the state of India-China relations?

MENON: Well, about 15 years ago is when we first started seeing signs of trouble in the relationship. We had a modus vivendi, which had been worked out through the ‘80s between the two countries of how to handle our differences and how to keep peace on the border, which was formalized during the [Prime Minister] Rajiv Gandhi visit in 1988, which was fairly simple. It was that we will settle all our differences peacefully. We’ll negotiate them. But while we are negotiating them, we will also cooperate where we can, both bilaterally and on the international stage, and that we would maintain the status quo on the boundary, as it were, on the border. That was formalized in an agreement, Border Peace and Tranquility Agreement, in ‘93.

But this started fraying, I would say, by about 2008, 2009, when we first started seeing incidents on the border of the Chinese troops changing their behavior, trying to extend roads, stay on what we considered our side of the Line of Actual Control and so on.

And when other issues in the bilateral relationship also started coming up.

China’s behavior in the neighborhood, in South Asia, also changed. There was much more willingness to get involved in local politics in India’s other neighbors, in Nepal and Sri Lanka and so on.

So, I think the first signs of difficulty were really around 15 years ago. And that’s exactly when India started taking what we regarded as countermeasures. We raised two mountain divisions in 2010, 2013, raised a mountain strike corps, started opening up advance landing grounds.

There’s a larger political context as well. The India-U.S. civil nuclear agreement had been signed in 2008; the defense and other relationships with the U.S. were booming; and China’s relationship with the U.S. was steadily deteriorating. I think it was still an open question. But we started seeing various signs of friction. The Chinese started objecting to our drilling for oil in the South China Sea, for instance, and Vietnamese concessions. And lots of little signs.

So, I would say that, 15 years ago, it would have been a mixed picture and one would have said, yes, there are signs of trouble, but perhaps we can handle them. We’ve handled these before and let’s see. We’d have been much more optimistic than we are today, I think. I don’t know if Vijay would agree with that.

MADAN: Ambassador Gokhale, 15 years ago and also, for both of you 20 years ago, if I’d asked you how you would have described it, Ambassador Gokhale?

GOKHALE: Yeah, thank you, Tanvi. I broadly agree with what Ambassador Menon has said. And just to add to that, if I were to describe the relationship 15 to 20 years ago, I’d use the words stable, neutral. Because we weren’t friends, but we weren’t adversaries either. But it was a relationship lacking in trust. There was a trust deficit. Otherwise, broadly, I think Ambassador Menon has already outlined that the slide had begun after 2006 and 2007 and already the strains were showing in that relationship.

07:27 The relationship since 2008

MADAN: I want to pick up on this idea of and dig down a little bit deeper into this 2006 to 2008 period that both of you mentioned. Ambassador Menon, you mentioned a few of them, but what were you seeing in that period in this 2006 to 2008 period, where you saw the change, what were the signs then?

MENON: Frankly, much of what we now regard as more assertive Chinese behavior, whether in the South China Sea, with Taiwan, in the Senkakus, Diaoyu, East China Sea with Japan, on the India-China border—much of that began in that period in Hu Jintao’s second term as it were.

And there are different explanations for this. One, of course, is that China realized that her relationship with the U.S. was no longer going to be as smooth as it had been before. But there’s a chicken-and-egg problem here—which came first, it’s hard to explain.

I tend towards internal domestic explanations for Chinese external behavior. It’s just what I find. I think the succession struggle to Hu Jintao had already started and ultimately culminated in Bo Xilai, the whole Bo Xilai crisis. And this is a period where I think Xi Jinping became chairman of the committee which was handling South China Sea. And if you look at it, I think this more assertive, nationalistic Chinese posture abroad, across the board, on the entire periphery—it seems to me that the India-China border and the relationship with India became part of that, became caught up in a larger thing.

By about 2015, 2016, Chinese scholars and even officials sometimes started saying that India is no longer neutral or no longer nonaligned, implying that we’d gone over to the dark side, to the U.S. And by then I think China-U.S. relations became a dominant prism through which they looked at almost everything around them.

In fact, that’s still a problem. I believe that India-China relations are sui generis; they have their own logic, their own reasons. But so long as China looks at it purely as in terms of its great power relationships, whether with the U.S. now or previously with the Soviet Union, there’s been trouble in the relationship.

MADAN: Ambassador Gokhale, what was your sense of what was both going on during this 2006 to 2008 period? And also similarly, what were the explanations you looked to? Was it domestic? Was it the relationship that China was having with the U.S.? Was it the global financial crisis as well and how various countries fared?

GOKHALE: Well, many of the reasons have already been outlined by Ambassador Menon. I just have one additional point to make. This was the ten years between 2000 and 2010 that the economic gap between India and China widened all of a sudden. In the year 2000, the ratio in terms of GDP was 1 to 2. India’s GDP was around half a trillion dollars. China’s was just over 1.2 trillion. But by the end of 2009, the end of the decade, India’s GDP was still around 1.2 or 1.3 trillion, and China’s GDP had crossed 6 or 7 trillion by then.

So, I think that the economic differential, the military differential that had emerged, as well as the diplomatic differential that emerged—because China became much more assertive on the global stage—perhaps led them to feel that they need not remain sensitive to India’s interests or concerns.

But I agree with Ambassador Menon that the Indo-U.S. relationship, the domestic situation within China politically speaking, and the sense that China had arrived on the world stage during the global financial crisis were all factors that influenced their perception of India.

11:45 The uneasy state of India-China ties today

MADAN: I’m going to fast forward a little bit to the present day from that period 15 years ago and ask you, Ambassador Gokhale, I’ll start with you this time, how would you describe the state of India-China ties today? And then in the next round we’ll dig a little bit deeper into why we got here and what happened between 2008 and today. But how would you describe the relationship between India and China today?

GOKHALE: So again, Tanvi, if I were to use a few words, I’d say the relationship is shaky. I’d say that there is a negative bias in the relationship now, and I would certainly feel that there is a deepening of mutual suspicion. And as a result, the India-China relationship is fraught with tension and uncertainty, which was not the case even 15 years ago.

MENON: I would agree with what Vijay just said, that it is a difficult relationship. And it’s because there is a disjuncture in the relationship. Politically, it’s at an impasse after what happened on the border in 2020 spring, with the PLA trying to change facts on the ground and not reverting to the status quo as it was before April 2020—despite 18, I think, rounds of talks between the corps commanders and so on. So, there is a political impasse.

But economically, the relationship still seems to be booming, if you look at the trade figures and so on. And there is a structural interdependence economically. Last I saw something like 28% of the value add in Indian exports is of Chinese origin, which, you know, suggests to you that both economies are really tied to each other, with the Indian economy much more dependent perhaps than the Chinese on the Indian.

And this kind of disjuncture makes for a very uneasy relationship. It’s not a good basis, quite apart from the differential in power which Vijay mentioned. And therefore, the unpredictability of the relationship. I think it’s more than just a question of stabilizing it. It’s a question of how do you address these elements of uncertainty in a relationship which you had managed. You might not have settled the issues or made tremendous progress, but you had managed for a considerable period of time. But that seems to be in jeopardy today. So, I would agree entirely with what Vijay said.

14:17 What the India-China border dispute is about

MADAN: Ambassador Gokhale, we’ve heard the border mentioned a few times. For the audience who is not too familiar, what does the border dispute between China and India entail?

GOKHALE: Well, the Chinese argument is that the boundary between India and China was never historically delineated. In other words, even preceding governments, governments preceding the current regimes, had not bilaterally agreed to the boundary alignment. And, therefore, there was a traditional and customary line, and the two countries differ in where that traditional and customary line lies on the ground.

Now, that is, of course, not the Indian position. India’s position is that in all sectors there is a traditional and customary line, of course, but it has also been sanctified through treaty and through convention and practice. And that it is now a matter of the current governments, or the current states—the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of India—simply committing to paper and on the ground in terms of boundary pillars, a boundary which they have already known for at least a century.

But I just want to add that the boundary question, of course, in my mind is symptomatic of a larger problem in India-China relations based on the differences in approach that both sides adopted after we became independent and the People’s Republic of China was established. They tended to see everything in the triangular competition between the United States, the Soviet Union, and China, as Ambassador Menon spoke of a short while ago.

Whereas in our case, whether the relationship was healthy or not, we have always placed China in an important position in our foreign policy. And therefore, as Ambassador Menon said, India-China relations are sui generis. And I think that difference of approach is reflected in a series of problems that have arisen in the relationship over the past 70-odd years.

MADAN: And just following up on that, I want to deep dive a little bit into what happened a few years ago, what brought us from stable to shaky, as Ambassador Gokhale put it. One of the things that struck me in 2020 when there was a border crisis, a standoff, is that all of those of you who have been China hands for several years within the Indian government, all of you to a person, noted that this was a different border crisis or standoff than the previous ones, the recent previous ones have been. I want to get into why, but before I get to 2020 and the border standoff, were there border standoffs before 2020 and in that 2008 to 2019 period, say? Ambassador Menon?

MENON: Yes, there have been. In fact, there’s been a sort of gradually escalating series of crises. In 2013, the Chinese tried to come in and stay permanently in Depsang in the extreme north of the western sector. But then India took certain actions and they withdrew within three weeks. And then after that, there were other attempts by China to change the status quo across the Line [of Actual Control]. Some of them were met successfully. Some they came in, stayed for three weeks in September 2014, when Xi Jinping was visiting, and then withdrew.

I think the biggest face off, of course, was in Doklam in 2017 when the Chinese came to what we and the Bhutanese regard as Bhutanese territory. And Indian troops then confronted them. And finally, both sides withdrew.

18:23 Spring 2020 border clashes

Spring 2020, though, was different in a fundamental way. For the first time, the Chinese tried to change the status quo in several places along the line in their favor, and to stay permanently on what we considered our side of the line in places that they had never been before, and to prevent us from patrolling areas which we had traditionally patrolled. And they did this simultaneously along the line in several places, which suggests a level of coordination, planning, and high-level approval, which had not been the case in previous such incidents. I’m sure they all involved high-level approvals in the Chinese system because the PLA is a political instrument primarily and the party does control the PLA all the time.

But I think this attempt to escalate probably came from a sense of military superiority in the sense that deterrence had clearly broken down, because we’re talking here about effective deterrence on the line.

But also, I think from a larger strategic sense—because there have to be larger strategic or political goals to justify something like that—basically going against the various agreements which they had respected in the past but tearing them up and changing the status quo. And so, one has to look for larger reasons for this.

It wasn’t entirely a surprise. Some of us have been warning about escalating Chinese changed behavior. But I think the scope and scale of it and the sheer brazenness of it was I think is why you saw that unanimous reaction across the board from not just those who had been involved, but even others.

And since then, actually, the situation hasn’t yet been stabilized or addressed. I mean, the root causes of this we still have to establish. We haven’t gone through the sort of detailed political reckoning on both sides and understanding—or agreed on a set of measures to prevent this happening again. In fact, the Chinese attitude seems to be, oh, you know, that’s over now, let’s put that behind us and let’s move on. Which leaves the possibility of it happening again open, and suggests that from the Chinese side, they might be quite happy to maintain this threat. Whereas India’s stand has been that we need to address these issues and restore the status quo if we are to have a normal political relationship. We can’t just ignore what’s happened.

My own preference would be that that we actually start a real strategic dialogue with the Chinese and begin with the simple things, with which CBMs [confidence-building measures] still work, which don’t work, crisis management measures, simple things on the ground. I’m not saying that these will restore trust. No. Because we have such a long history on that border. But you at least want the confidence that you can manage the situation, that you can stabilize it to start with, and then see whether you can actually build a relationship. But today, it’s still very hard to see.

MADAN: Ambassador Gokhale, how would you describe what happened in 2020 and why you felt that it was different from the previous crises or an inflection point? You’ve said elsewhere that it’s led to India and China going from peaceful coexistence to armed co-existence. What made 2020 different and what exactly happened at the boundary?

GOKHALE: Well, the 2020 incident was, as Ambassador Menon said, in the wake of a number of earlier incidents that had happened. And during those incidents, the framework that had been built by the two countries after Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s visit gradually disintegrated. And therefore, when the developments happened in 2020 at multiple points along the LAC, it resulted in the first fatalities that we have had on the boundary or on the Line of Actual Control in perhaps 45-odd years.

Now, the Galwan incident and the other incidents are significant not only because of those fatalities, but because the situation along the boundary has fundamentally changed. In other words, there is enhanced activity in terms of military deployments, but there is also enhanced infrastructure building. And my sense is that even if we want to return to the status quo ante of 2019, it may not be possible to do so now, both because of the infrastructure built by both sides and because of the deployment of troops, which unless the trust deficit is bridged, will be difficult to reduce in any significant number.

23:34 Is India moving the goalposts on the border agreements?

MADAN: Ambassador Menon, you mentioned the agreements. One thing sometimes you hear from Chinese analysts is they say that India has changed the goalposts. Because we’ve heard the government of India say that the situation at the border has been disturbed, and that the broader relationship between India and China cannot return to normal, or return to what it was, as long as the border remains not normal and as long as peace and tranquility hasn’t been maintained at the border. You have Chinese analysts saying this is changing the goalposts and that India is now asking for the border dispute to be resolved. Is that how you see it or what did the agreement say? Because India is saying this is a violation of the agreements and the Chinese are saying that India has now changed the goalposts. What is your assessment of what exactly is the violation of agreements that India sees? And is it China that has a different impression of what India is asking for?

MENON: I think you’ll notice that this is said by analysts, not by the Chinese government, because the Chinese government committed itself in writing and in an international legal treaty in 1993 and 1996 and thereafter, several times, to maintaining the status quo on the border, not changing the situation on the ground, and to resolving any issues that might arise peacefully. Instead, we had people dying on the border for the first time in 45 years by adversary action in 2020 spring. So, if anyone has shifted the goalposts or their understanding, I think it’s Chinese analysts. It’s the analysts who are saying this.

Now, this is not new, frankly, in our experience. When you go back, what China has said about a boundary settlement has varied over time. From saying we will do a package settlement, we will be reasonable, we will recognize the present situation in the eastern sector if you accept what we’ve done in the west and so on to now they say no, there’s no question, India must first make concessions. 1985 they started specifying which areas they wanted, including Tawang and so on.

So, I mean, China has, depending on her perception of the relative balance of power on the border, has, I think, negotiated and adjusted her stand accordingly. And frankly, she doesn’t understand, I think, that not everybody else operates quite the same way the Chinese do. I think they project on others what they do. After all, they were as good as loyal allies of the U.S. until the global financial crisis, as long as they believed that was the balance of power that existed. Once they thought their moment had come with the global financial crisis, they changed their behavior. And that’s what we were talking about after 2008.

So, it’s a bit disingenuous for Chinese analysts to say that India’s shifted the goalposts. India has always maintained that peace and tranquility on the border is essential if the relationship is to be normal and is to progress. We’re a democracy—people are not going to understand this, that you can have a live border with the threat of Indians dying on that border and of the border being disturbed or India losing territory to a neighbor, and still expect life to go on as usual with that neighbor.

Frankly, I haven’t heard a good explanation from the Chinese side for why they did what they did in 2020. I think this is part of the problem. And therefore, you hear arguments like this.

27:32 A shift in Indian public opinion on China across the board

MADAN: Ambassador Gokhale, what is your sense—even if it’s a few different explanations that you have—for why China did what it did, as Ambassador Menon put it?

GOKHALE: Well, I think, Tanvi, that they seem to have concluded that either India did not have the capacity for geopolitical backlash or lacked the political will to do so. All the reasons that Ambassador Menon outlined perhaps fed into that view in the Chinese strategic establishment.

And perhaps there was some kind of a strategic miscalculation there, because the subsequent response which came across from the Indian side in all the stratas of society—and I think Ambassador Menon mentioned that across the board this was condemned—suggests that there is a new paradigm in which Indians are looking at India-China relations.

Now, of course, whether the Chinese get that or not is something I am not clear about because I haven’t spoken to any of them over the last few months. But I presume that if the Chinese embassy is actually following developments in India, it should be fairly clear to them that even those who were willing to give the benefit of doubt to the Chinese side, today are no longer willing to give them the benefit of the doubt.

So, there has been a shift in Indian public opinion across the board: governments, strategic community, media, even business. And I think that is going to impact on the future of the relationship.

29:06 China’s changed posture on India’s periphery

MADAN: I want to come back to the future in a few minutes. But I do want to also talk about [what] we mentioned, the boundary. Ambassador Menon, if tomorrow the boundary situation stabilizes or even if we waved a magic wand and there was a boundary solution found. I want to pick up on something Ambassador Gokhale said, which is that the boundary dispute is a symptom of a larger set of problems. What are the other concerns that India has when it looks at China, whether it’s China’s other relationships, its presence, its vision of the region, what are those other concerns that India has?

MENON: Well, one, of course, is the changed Chinese posture in our immediate periphery in the Indian subcontinent. And her willingness now to be involved in the domestic politics of our neighbors, whether it’s trying to get the two communist parties to work together in Nepal or making clear her preferences in Sri Lanka’s internal politics and so on. Myanmar is a very good example of very deep Chinese involvement in internal politics of a neighbor.

Ultimately the Indian periphery, large parts of the Indian periphery are also China’s periphery. So we rub up against each other in that periphery. So, depending on how successful we are in managing the relationship, this is going to be one of the elements of how we manage the relationship.

But there is a broader problem. Over the last 10 to 15 years, I think that there is an increasing conviction among Indians that China’s the only great power which actually opposes the rise of India, that does not see India’s rise as being good for the international system or themselves. And the proof of that, I mean that most of the public would say, is China’s attitude to India’s quest for a permanent seat on the UN Security Council. But there’s other instances: even membership of the NSG [Nuclear Suppliers Group]. And there is that fundamental sense that somehow China stands in the way, China does not want India to rise.

And there is some academic support for this as well. If you look at China’s attitude to her periphery, the Korean Peninsula, Indochina, South Asia, China seeks to keep the periphery divided, free of outside great powers, and keep it relatively weak and therefore dependent on China. And Central Asia and so on.

I think that’s the core problem. And I know that is a mantra that both Indian and Chinese leaders have used in the past, that there is enough space for both India and China to develop, that China is India’s development opportunity, India is China’s development opportunity, et cetera. But I think what’s actually happened in the relationship over the last 15 years or so has made those sound less and less convincing.

So, we actually have a much broader set of issues: China’s behavior in the Indian Ocean, building her first military base in Djibouti, but with the possibility of using other bases and so on and so forth. I mean, India’s interests in peace across the Taiwan Strait, I mean, 38% of India’s foreign trade goes through the South China Sea and past Taiwan.

And so there’s a whole host of issues on which there’s possible friction, which is why it’s important that you start with a proper understanding and a dialogue between the two of you if you want to have any hope of managing these things and turning this shaky, unproductive relationship into something that it is a little more predictable, a little less shaky.

32:52 Do India and China have a similar vision of the Indo-Pacific region?

MADAN: Ambassador Gokhale, do India and China see the region—Asia, Indo-Pacific, whatever your preferred term is—do the two countries have a similar vision of the region?

GOKHALE: No, I don’t think so. I think that’s part of the problem. If you look even in the 1950s, you know, the Indian approach was that Asians must shape the Asian post-Second World War order, but that India could not do it by itself. It needed other similar-minded countries. And certainly, among them were the People’s Republic of China, Indonesia, and so on. And that, I think, remains the general approach today, that India does not believe that it alone can shape the region and it requires partners and friends to do so.

The Chinese approach was very different. They thought that they had won the Second World War, that they had defeated Japan in the Pacific, and that they had the right to shape that Asian order without anybody else being given equal status in that process. And that persists till today because, as Ambassador Menon said right at the beginning, everything is looked at from the Sino-U.S. prism, without recognizing that India has abiding interests and concerns in the region which pre-date anything that happened in the Second World War and even anything that happened before the colonial period. So, I think that really is the issue.

I also just wanted to amplify a point, a very valid point that Ambassador Menon made about changing perceptions. If you were to take a poll, say in 2014, among the university students in India on China, the vast majority looked at China as something aspirational. They admired the GDP growth, the improvement in lifestyle, the introduction of new technologies and so on and so forth. I think after Galwan [in 2020] if you were to take the poll, a very large number of them, probably a majority, would first talk about the tension and problem that China is creating on the border.

So, I think what we are seeing is a long-term impact of the Galwan incident. And I don’t think that will be so easily resolved as and when we start the dialogue. But I do agree with Ambassador Menon that you cannot delay a dialogue between two nuclear-armed neighbors with difficult relations. That has to start at some point, but it won’t change the situation that easily.

35:26 What are the areas where India and China are still cooperating?

MADAN: The description I’ve heard of a similar effort that the U.S. is undertaking is the idea being to stabilize, not necessarily expect any improvement of the relationship. So, stabilization and dialogue rather than expecting improvement.

Ambassador Menon, I do want to pick up on something you’d said earlier, because we’ve talked about now the concerns. There was a period in which there was a phase of cooperation, of engagement, where the bilateral as you said economically, you talked about trade, but also in the multilateral sphere where India and China had been cooperating. What are the areas where you still see India and China engaging—or having the potential to cooperate—that are still present in the relationship?

MENON: Well, some of them are weaker than before, but frankly, in their common interest. We had worked together in the BASIC [Brazil, South Africa, India, China] group on climate change, for instance, in international negotiations on climate change. We’d also worked together on international trade issues together because frankly, we both have a major interest in keeping the world economy from going entirely protectionist or being divided up and fragmented into smaller or large trading blocs—especially India, which is not a member of any of the regional trading agreements.

But in each of these cases, I think the impulse has got a little weaker than it was, say, ten years ago or five years ago. Even though logically it’s in our long-term self-interest to start addressing climate change issues, to start finding ways forward on trade issues, and so on. This would be logical.

But this is where it hurts not to have a functioning, normal political relationship. And this is why I really think, as Vijay just said rightly, Galwan is not just about the border. It’s had long-term effects in many ways, and it prevents the two largest emerging economies of co-operating together in a whole host of issues where they could work together.

Partly it’s because both India and China have evolved also in their own views and their approach to the international system. If you compare it to ten years ago, I think both countries are less open, much less convinced that there’s an enabling climate or environment in which they’re operating.

But most of all, I think it’s because China has turned inward and China is going through a very complicated adjustment, not just economic, but actually of the political and social contract as well and has some big choices to make about her future as her growth slows, as her demography works against her.

So, in that situation—where you don’t have a normal, proper dialogue, you don’t have normal political relationships, where you see a much harsher world environment in which you’re operating, and where one of the countries at least is going through a huge internal churn—it’s hard to be optimistic about them working together even where there is a clear common interest.

38:50 Four trends evident in India’s recent approach to China

MADAN: Ambassador Gokhale, given these concerns and particularly after the fatal clash at Galwan in 2020, what is the approach that India has been taking the last few years to deal with this challenge as it sees it from China?

GOKHALE: Yeah, well, Tanvi, I think there are four trends that I notice. Of course, whether these are in the short term or the longer term are still to be determined.

But from the statements made by the Indian leadership, it’s quite clear to me, first of all, that the boundary question has been brought back into the front and center of the relationship, and this is likely to continue even if there is an improvement in the political climate.

Secondly, the public debate in India very much these days centers around the concern that we are economically heavily dependent on the Chinese. I think Ambassador Menon also mentioned this. And there is talk of de-risking. Now, of course, this is a very overused phrase, not only in the Indian context, but in the European and American contexts as well. But in the Indian context, I think there is concern that some of our strategic industries are heavily dependent on Chinese imports and we need to do something about it.

Thirdly, I think it’s very clear that India is looking at strong partnerships in the Indo-Pacific for balance because China is, after all, an $18 trillion economy with a huge military capacity. And therefore, some amount of balancing is needed.

Lastly, if I were to go on the basis of statements made by the government and even by civil society, I think there is at least an effort to prepare public opinion for a longer-term competition with China. I don’t, of course, mean that there is, at least on the Indian side, an effort to generate hostility, but I think there is a concerted effort to refocus the threat, if I were to use that word, from our western neighbor to our northern neighbor. And I think that trend is likely to continue even if the political climate improves.

41:05 Should India deepen ties with the U.S., or hold back?

MADAN: The western neighbor, of course, being Pakistan, India’s other rival, with whom China has a very close relationship going back to at least in the early 1960s.

Ambassador Menon, I want to pick up a thread from Ambassador Gokhale’s four points—the third one on building partnerships. Of course, we’ve seen India deepen ties with the U.S., with Australia, with Japan, with France, with Britain, even countries like South Korea and then some Southeast Asian countries.

I do want to ask you, though, both of you have mentioned the India-U.S. relationship. How does India balance this desire to deepen ties with the U.S.—not just because of the rivalry with China, but also because of its own economic transformation, technological transformation—how does it balance that with the fact, or does it need to balance that with the idea, as both of you have talked about, that China sees India through a U.S. lens, a China-U.S. lens? There have been some in India who have previously, I haven’t heard it recently, but used to argue that India should hold back from deepening ties with the U.S. and others so it doesn’t provoke China. Is that still something people talk about? Is that something India should be doing?

MENON: I’ve never understood anyone who says we should hold back on our relationship with the U.S. because of how China feels about it. I mean, our job is to ultimately to deal with India’s interests, to promote India’s interests. And India has an interest in working with the U.S. I don’t see how we can transform India if we are to have bad relations with the two largest economies of the world, both China and the U.S.

And the U.S. has always been supportive. I mean, we worked with the U.S. to do the Green Revolution in the ‘60s when quite apart from the political relationship, the U.S. has always been essential to India’s transformation. And that’s going to continue.

So, from an Indian point of view, that is really the driving force. The geopolitics is jam. And, I’ve said myself that China maybe is the strategic glue in the relationship today because for the U.S., the U.S. sees this relationship too, from a geopolitical point of view, from the standpoint of its effect on its relations with China. But for me, the primary driver of it from an Indian point of view is really India’s transformation.

So, for India to then say, oh, because somebody else will be offended, I’m not going to do what’s in my interest doesn’t make sense to me. Today, India and the U.S. have transformed their relationship over the last two and a half decades. They do almost everything that allies do. And when you see the depth and the breadth of what we’re doing, it’s really quite impressive. I don’t think anyone would have predicted this 20 years ago.

43:03 India deepening ties across the region

But as you said, it’s not just India and the U.S. For India’s transformation we need to work across the board, through the Indo-Pacific and the entire maritime Asia. You look at the relationship with Japan, or with Indonesia, with the Philippines, with Vietnam, with Singapore. These have all today qualitatively being upgraded. And even the relationships much closer home have changed considerably.

So, if the China challenge leads us to do what is good for us, frankly, I welcome it. And if the China challenge also brings us new friends who are willing to cooperate with us, I mean, that’s good news. In fact, I think we owe some of our friendships to the Chinese; we should be grateful to them for that.

But what you’re seeing now is a multi-directional Indian policy. Balancing China is one part of it. But more important is embedding India in relationships which help to create an environment within which India’s transformation can be enabled. And that’s, for me, the ultimate goal of this.

China can choose to be part of that. Could have.

After what’s happened, and especially after Galwan [in 2020], that choice seems very difficult for China to make, and China doesn’t seem to have made that choice.

In fact, it’s for me a conundrum. Why has China chosen to alienate so many of her neighbors in the last ten years?

And she has offered her own vision recently in a Global Security Initiative, Global Development Initiative, the whole Belt and Road Initiative, et cetera. But these are all China-centered ideas.

And why didn’t she choose a cooperative framework within which to work with her neighbors and others? I still don’t understand that because it seems to me that would have served both the region and China herself better than what we’ve seen instead.

Today, you look at what’s happened to the India-China relationship thanks to Chinese actions. You look at what’s happened to China-Japan relations. Which leads me to believe that you therefore have to go beyond traditional IR [international relations theory] explanations or rational explanations for behavior, and you end up then with personalities and ideologies and other “irrational explanations.”

46:31 What would détente between India and China require

MADAN: Ambassador Gokhale, any thoughts on that? But also, I was going to ask both of you a question on—we’ve heard a lot of chatter, especially in Western publications actually—about an India-China détente or even friendship. I’m taking it from what both of you are saying is that is not on the cards. But what would it take— you both have mentioned return to some sort of dialogue—what would you have in mind? Both in terms of what would the objectives of the dialogues be and what are the realistic expectations of something like that? And what are the limits of that kind of process as well that people should keep in mind?

GOKHALE: Well, you know, when you ask me whether there is any possibility of détente or friendship, as a former diplomat anything is possible. Right? But if you ask me, is friendship likely, I would say no. If you say, is détente likely, I would say it is more likely. But I think it needs two to tango, or two to clap hands. And I would say that there will be a couple of, I wouldn’t use the word preconditions, but certainly a couple of circumstances that have to change if that détente is to take place.

Firstly, I think we need to go back to respecting the status quo along the border region of the two countries. In other words, we should go back to a stable and predictable border regime which gives a sense of security to both sides.

Secondly, I think there needs to be a return to a favorite Chinese phrase, which is we must show mutual sensitivity to each other’s concerns and interests—which in the 2010s meant that India must show concern for Chinese interests because they’re global, but China need not reciprocate because India’s interests are very local, and therefore it’s not a big issue. I think we have to go back to respecting each other’s mutual interests and concerns.

Thirdly, I think the whole issue of sharing space, which Ambassador Menon alluded to, because as he said our strategic peripheries are colliding, means that certainly we need to respect each other’s positions in those shared spaces. And that does require a recognition that India has a very long-standing historical, cultural, and geographical connect with all of South Asia, large parts of Southeast Asia, and the Indian Ocean region.

So, I am not saying détente is not possible, but I don’t think the conditions for it exist as of yet. At the moment I think our engagement is basically risk management or risk mitigation, and there is no political dialogue to speak of.

49:20 What is the chance of crisis escalation between India and China?

MADAN: Ambassador Menon, on the flip side, what are the prospects of a crisis escalation in the India-China relationship?

MENON: Well, in this case, it’s the Chinese who took the initiative to change the situation and the nature of the relationship. And what they are signaling now is that they like this uncertainty by saying, let’s put this behind us and let life go on as normal without addressing the issues and without actually trying to make sure that this doesn’t happen again. So, it’s not as though they’re signaling some great unhappiness, which they are about to try and change. So, they’re not going back, but they’re not going forward either.

I think the Indian government has made it clear that what it wants to do is to restore the peace and the tranquility on the border and that this is its first priority there. So, it’s done what it needs to in terms of defensive steps—military deployments and so on, building new infrastructure.

So, is there a risk of this escalating? I mean, you can never rule this out when troops are facing each other, over a hundred thousand troops along that line, at these altitudes. You can never say there’s zero risk. But I wouldn’t say that the political conditions exist right now for this to escalate into … there could be incidents. And the risk is without, as I said, crisis management measures in place or understanding of CBMs which work and so on, and good channels of communication.

With that, these things could be unpredictable; could get out of hand.

But I don’t see the political interest on either side. We’re going in for a general election next year. No government wants to face that kind of thing when it’s also facing an election. And on the Chinese side, as I said, they seem happy with the uncertainty, with the threat in place, as it were, a threat in being. So, I’ll never rule it out, but yes, I don’t see it as imminent or somehow explosive.

51:26 Areas of potential competition and cooperation in the coming years?

MADAN: Ambassador Gokhale, looking ahead, if you had to flag a few things in terms of the future trajectory or key issue areas of competition or cooperation in India-China relations, what would you tell our audience that they should keep an eye on? Or what are you keeping your eye on, two or three things or even more over the next few months, the next year, or the next couple of years?

GOKHALE: Well, one is, of course, what sort of leadership-level interaction takes place over the coming months and years and what are the concrete outcomes? Do the leaders meet, and do they build, rebuild mutual understanding? Do they actually set some goalposts together for the two sides to achieve? I think that’s an obvious thing to look out for.

I think if there is a shift in their view on the border region, if there is a willingness to resolve the two current outstanding issues leftover from 2020, or if we see other ground level changes—let us say de-escalation and even de-induction of forces—I think that would be a, could be a signal.

I’d say also that in India at least, we would keep an eye on the state of relations between China and the United States because they are the two most consequential powers in the world. And anything that they might or might not do together will influence and impact all the rest of us.

If you were to ask me an immediate sign, I would certainly say that it is unnatural that the Chinese have not appointed an ambassador in New Delhi for close to a year. So, if that takes place, that too I think would be at least an indication that there is a willingness to move things forward.

But I just want to also add to the previous answer that Ambassador Menon gave. I agree with him that the Chinese tactic so far has been gray-zone warfare, or military operations other than war. I find it difficult to believe that they would want to engage in a larger scale conflict which would turn the relationship very adversarial. I don’t see how it benefits them. Of course, governments and countries don’t necessarily act logically. But if we were to assume that the decision-makers in Beijing were rational people, then it is unlikely that there will be an escalation in the situation. Except if there is a catastrophic development in the region, and I would think that the Taiwan Straits crisis might be that sort of a trigger, but that would be very speculative.

54:11 Lightning Round: What is the biggest myth about India-China relations?

MADAN: I will then ask you the lightning round question. We’re going to ask this at the end of every episode. We have a choice of a few, but I’ll ask you the one that is on top of my mind: what do you think is the biggest myth or misunderstanding that you hear about India-China relations? Whether it’s in India, whether it’s abroad, what do you think that biggest myth is?

MENON: That this is all some historical animosity, it’s a question left over from history. We’ve been independent 75 years now. We’re grown up. I think we take responsibility for what we do. It’s convenient to say this is all left over from history and blame the British for whatever there is and we’re not responsible. And maybe it opens up space to compromise. But it’s time, I think, that leaders on both sides took responsibility for what they do and say.

MADAN: Ambassador Gokhale?

GOKHALE: Well, I’ll tell you what I think is the greatest myth the Chinese are spreading: that relations between India and China for the past 2,000 years have been 99.9% good and only 0.01% bad, which is an aberration. Because, you know, frankly, the two countries don’t have much of a history together over 2,000 years. I think Tibet separated us. There was no real direct political contact. Trade and spiritual exchanges and cultural exchanges continued. But you can’t really characterize this as a deep-seated relationship which was fine for 99.9% of the time. The Chinese, of course, love spreading this myth.

MENON: In fact, just to add to what he said: we had a relationship with Tibet, we had a boundary with Tibet, which was agreed with Tibet for the most part. We didn’t have a boundary with China until the PRC invaded Tibet in 1950. And that’s one of the myths that whatever Tibet did that somehow that all that devolves on China. I mean, historically, they’re quite ahistorical in the way they apply history to serve today’s purposes.

MADAN: In fact, that connects to my myth—and this often comes [up] here where I’m sitting in the U.S.—which is that India-China frictions are fairly new and only [just] started, that there were concerns about China only in 2020. When it actually does go back, even in independent India to almost the beginning, if not the 1950s, and that it’s only India of all the Quad—Australia, Japan, U.S., India—that has consistently seen China as a challenge since the 1950s.

[music]

With that, Ambassador Menon, Ambassador Gokhale, thank you so much for joining us for this inaugural episode of the Global India podcast. We know that some of the issues you mentioned we’re going to have additional details and episodes on these in the future. But thank you very much for joining us.

GOKHALE: Thank you.

MENON: Thank you, Tanvi.

MADAN: Thank you for tuning in to the Global India podcast. I’m Tanvi Madan, senior fellow in the Foreign Policy program at the Brookings Institution. You can find research about India and more episodes of this show on our website, Brookings dot edu slash Global India.

Global India is brought to you by the Brookings Podcast Network, and we’ll be releasing new episodes every two weeks. Send any feedback or questions to podcasts at Brookings dot edu.

My thanks to the production team, including Kuwilileni Hauwanga, supervising producer; Fred Dews and Raman Preet Kaur, producers; Gastón Reboredo, audio engineer; and Daniel Morales, video editor.

My thanks also to Alexandra Dimsdale and Hanna Foreman for their support, and to Shavanthi Mendis, who designed the show art. Additional support for the podcast comes from my colleagues in the Foreign Policy program and the Office of Communications at Brookings.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

PodcastA big-picture look at the India-China relationship

September 20, 2023

Listen on

Global India Podcast