Introduction

Chairman Pitts, Ranking Member Pallone and Members of the Subcommittee – as a practicing physician and Fellow at the Engelberg Center for Health Care Reform at the Brookings Institution, it is a privilege to participate in this hearing today. I commend the Committee for its willingness to confront the difficult issues surrounding Medicare payments to physicians by looking to innovative clinical practices, ideas and solutions.

The current problem of physician payment is not new. Its history can be found in a series of bipartisan legislative efforts aimed at creating a stable system of Medicare physician payment rates and yearly updates to keep health care spending in line with overall economic growth year over year. First, legislation creating the Resource Based Relative Value Scale (RBRVS) was enacted in 1989 and led to the development of relative value units, or RVUs, for each of the physician-related services paid for in the traditional Medicare program. As the number of billable service codes grew over time, an extensive regulatory process was enacted to develop RVU weights and update them year over year. The goal of these updates was to keep the (relative) payments made by Medicare to accurately reflect the value of services.

The problem with this approach is the development of the term “relative.” Over time, the RVU updating system has placed an increasing importance, evidenced by RVU weights, on procedures, scans, and other technical services that fix certain ailments or problems. This has resulted in an emphasis on volume over value and the maintenance of silos in health care, which have eroded the quality of care we deliver to our patients. Non-technical or nonprocedural physician services, including for example “cognitive” services such as spending time with a patient reviewing the risks and benefits of a treatment course or a counseling session to understand health promotion behaviors, have not received significant RVU weight increases over time. Additionally, new services such as email consultations and new approaches to care such as nurse or pharmacist-led care management trams may not be included at all in the list of covered services. These omissions in the RVU system are even more significant as we head into an era of more personalized medicine where the right treatment at the right time for each patient is increasingly individualized-where some patients with heart disease may benefit from a certain imaging procedure but others may not.

The 1997 Balanced Budget Act inadvertently exacerbated the problem with the introduction of the sustainable growth rate or SGR. The SGR was intended to keep the growth in Medicare physician-related spending per beneficiary in line with growth in the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP). In the early years of the SGR, this worked fine, as spending growth was lower than the calculated GDP target and payment rates for physician services increased. But starting with the recession in 2002, spending growth per beneficiary began to exceed GDP growth. In 2002, payment rates were reduced accordingly, by 4.8 percent.

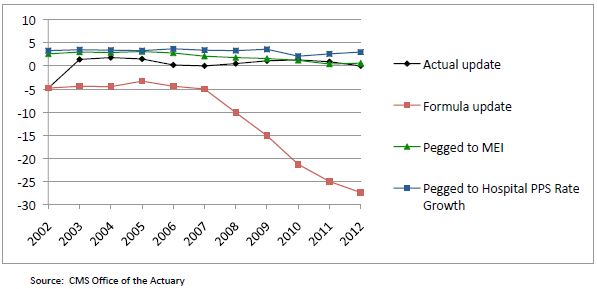

Every year since then, the scheduled SGR payment rate reductions have not taken full effect. Instead, because of concerns about access to care and the sufficiency of payments, Congress has headed off the full payment reductions on a short-term basis. Typically, this has involved offsetting at least some of the budgetary costs with payment reductions affecting other Medicare providers. These short-term patches have not kept up with inflation: between 2000 and 2010, the total cumulative increase in physician payment rates in the Physician Fee Schedule was 8 percent, while the “market basket” for physician services (the Medicare Economic Index) rose 22 percent.[i] As Figure 1 illustrates, actual updates as well as the SGR formula update still grow at rates far below input costs (MEI) and payment rates for other providers, thus exacerbating systemic flaws. The system is broken.

Figure 1: Percent (%) Change of Payment Update Under Multiple Scenarios

So here we are today, facing yet another possible physician payment cut of 27 percent, and we ask ourselves, “What can be done?” First, we must achieve a long-term vision for payment reform that will help chart a path towards clinician-driven, evidence-based medicine that preserves the autonomy of the physician-patient relationship while moving the profession towards greater accountability. Then, we must look to current innovations, especially those that are clinician-led to help us achieve broader system wide savings.

A Long-Term Vision for Innovation in Physician Payment

The goal of any meaningful Medicare physician payment has to have three essential elements. First, payments must incentivize coordination between providers and across different provider settings. The treatment and management of chronic diseases, acute illness, and prevention and health promotion does not occur within a single physician office or with a single physician or other provider for most individuals. It occurs between specialists in the hospital, in outpatient and rehabilitation facilities, in pharmacies, in community-based organizations, and in the home. The payment system must recognize that incentivizing providers to work together across these divisions is crucial to both the improvement of care for patients and the reduction in unnecessary, redundant, and sometimes harmful or deadly care. Up to $45 billion dollars in health spending each year are attributed to failures in coordination, up to $226 billion in overtreatment and up to $389 billion in administrative complexity.[ii]

Second, payments must inject flexibility into physician practices and clinical processes to remove the sole reliance on the provision of services, tests, and drugs as sources of income. The current fee-for-service model (FFS) incentivizes behaviors that are not in the best interest of patients in many cases and places the emphasis on volume over value and patient-centeredness. In addition, in the era of accountable care—that is, providers being held accountable for the cost and quality of the care that they deliver to patients through financial means—there are numerous elements of care that do not currently fit into the FFS model and are thus uncompensated. Services such as extended office visits, email correspondence, end-of-life counseling, comprehensive treatment plan development and tracking, and critical health IT infrastructure are not part of any fee schedule. Yet these elements of care have been proven to improve the quality of care and lower the overall total cost of care for patients. Any savings from investments made in these areas by providers goes straight to payers.

Third, payments must be tied to appropriate performance and quality measures and embedded into continuous quality improvement programs. This ensures against providers withholding care or providing cheaper care at the expense of patient needs to increase their income. This also reinforces incentives for physicians to adhere to established guidelines, practice evidence-based medicine, and treat patients individually.

With those three elements in mind, it is also important to reinforce that the transition to a new payment system for physician services must occur in stages. A switch to a complete non-FFS system cannot possibly happen in the short term. But it is critical to put into place a process to begin the transition away from a pure volume based, FFS system toward a flexible, blended payment system with payments tied to quality and performance measures, and aligned to coordinated care processes.

At the Engelberg Center for Health Care Reform at Brookings, we have been working with physicians, clinical societies, and other provider groups to start defining the pathway forward, and as a practicing physician, I understand how critical it is to work directly with these groups to make significant progress on this path. We also highlight several key efforts across a variety of specialists with tangible reductions in cost and improvements in quality.

Innovation in the Public Sector

A significant number of important steps to achieve meaningful payment reform have started within the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), including models for bundled payments, coordination among multi-payers in comprehensive primary care and Pioneer Accountable Care Organizations, but I will focus on reinforcing our long-term vision for physician payment by also highlighting where transformation is taking place outside of CMMI. These innovations are noteworthy since in some cases, they have been in place for years with little recognition and acknowledgement by public or private payers. In terms of advancing CMMI’s initiatives, there is broad consensus that the Secretary should advance payment reforms as quickly and responsibly as possible in order to create force multipliers that can achieve the long-term vision outlined above. In particular, I encourage CMMI to identify mechanisms to further their multi-payer efforts such that the important work will transform the delivery system. Finally, the recently announced Challenge Grants offer great insights into clinical innovation. A proposal by Dr. Barbara McAneny of New Mexico Cancer Center (NMCC) was awarded a CMMI grant to expand staff and hours of operation NMCC’s staff and hours of operation to provide an alternative to expensive and inconvenient emergency department services. Under the grant, NMCC will be comparing its quality of care and the cost of care with control-group practices and hospital-based systems. By the end of the third year, Dr. McAneny and her practice colleagues will have a better understanding of all facets of cancer care costs so they can provide a bundled payment mechanism. There is indeed great promise in these examples that should be brought to scale for the nation.

Innovations Informed by Clinical Leadership

Frustrated by the growing cost of care and the scarce time with patients to address important issues, physicians and other clinical leaders are already moving to implement delivery system transformations that are improving care and reducing the total cost of care, many of which are unfunded or uncompensated by payers but still offer the best promise for better care everywhere. Several of my fellow panelists will highlight these efforts.

For example, teams of physicians and health system leaders in Portland, Oregon have implemented an innovative cardiology program led by Drs. Xiaoyan Huang and John Peabody aimed at improving quality, lowering costs and advancing the patient care experience. Known as the Accelerating Clinical Transformation for Cardiovascular Disease (ACT-CVD) Program, the team is redesigning the care of cardiovascular disease by bringing together cardiologists, hospitalists, and primary care providers in a dense urban population in Oregon. Working toward a full-scale system transformation, they have changed care in two general areas: clinical and business. The clinical work has centered on identifying disease specific quality improvements, determining care coordination between specialists and primary care providers, streamlining workflows for high-risk patients, and adoption of appropriate use criteria. The parallel stream of business activities has led to the creation of a large cardiac disease episode of care/bundle to aggregate all cardiovascular costs (approximately $15,000 per patient per year for the high-risk population), the generation of budget expectations for the population, and new physician contract language that incorporates quality and the patient experience. Quality and savings opportunities identified include the following:

-

- Chest pain phone triage to reduce unnecessary ER referral and utilization

-

- Congestive Heart Failure Nurse Practitioner and Physician Assistant case management

-

- Use of comparative effectiveness research to ensure appropriate use of stress testing and teaching aids for students, residents and fellows to better understand true cost of care

-

- Tele-medicine consulting including live chat with cardiologists and electronic medical record review

-

- Co-management of high risk patients between cardiology, surgery, hospitalists, and primary care physicians

The Oregon ACT-CVD program estimates a potential savings of approximately $49.4 million in a target patient population of 77,000 lives connected by hundreds of cardiologists and primary care physicians. But the program still struggles to achieve broad scale largely due to competing incentives in the current reimbursement system—simply put, it is very hard to do this work when the innovations are not recognized by codes, claims, or payers.

Innovation led by physicians is also helping to shape interactions between the multitudes of specialists involved in medical decision-making around cancer care. Dr. John Sprandio, a medical oncologist in Pennsylvania, has changed his practice to promote the concept of a patient-centered medical oncology home (PCMOH). The concept advocates investments in electronic health records, standardization of documentation, physician document review processes, referring/consulting physician access to records, current and longitudinal data reporting, assessment plan development and customization, telephone triage, palliative care programs, and a number of patient tracking processes as the bedrock of their enhanced oncology provider model.[iii] Participation in quality efforts advanced by professional oncology societies gave Dr. Sprandio specialty specific quality metrics to ensure that his care was consistent with the latest guidelines and clinical pathways.

In just five years, Dr. Sprandio’s practice saw significant reductions in both ED visits and hospital admissions leading to significant savings to the system overall, but he faced a dilemma—he was still practicing in a RVU driven, FFS environment that did not necessarily reward any of these innovations, and as a result, there were times when Dr. Sprandio found it challenging to subsidize the coordinated care. Despite this, he persevered. Imagine if payment mechanisms were aligned to incentivize this type of coordination.

Innovation is also occurring in the fields of primary care and other specialties as physicians are consistently voicing concerns that the lack of support for meaningful communication between primary care and specialties results in a breakdown in the management of patients.[iv] A perfect example of an innovative solution to deal with this is in the field of behavioral health care. Patients suffering from depression often fail to seek treatment and primary care physicians often feel overwhelmed with cases that might require more intense monitoring or involvement of an already time constrained and often inaccessible mental health specialist. A multisite effort in the states of Washington , California, Indiana, Texas, and North Carolina (known as the IMPACT Project) aimed to deal with these issues began over a decade ago led by a team of clinicians and quality improvement experts. Primary care practices in eight FFS and capitated settings agreed to engage several depression care managers and a consulting psychiatrist who could electronically review charts and speak with the PCP regarding complex patient treatments. Cost of the care manager and consulting psychiatrist as well as research to study the program’s effects were subsidized by philanthropic foundations and internal resources. The care manager would ensure that close follow-up was scheduled and that care did not “fall through the cracks” as they often do in transitions between primary care and specialties. The consulting psychiatrist worked virtually, covering multiple practices at a time and working over weekends if necessary. Savings of approximately $896 per patient per year were sustained along with demonstrable improvement in mental health outcomes and other indices of chronic disease. Diabetics with depression improved their glucose control. The potential for scale is great, but incentives to change the system are few and far between and all too often, great cost saving opportunities go unrealized.

There are many more examples in additional specialties and primary care—all with the theme that reinforces the need for a payment system that is flexible to innovation but provides a path towards better coordination of care and quality improvement. There will be elements of the FFS system that will need to be retained in this transition and potentially beyond but that should no longer delay progress to achieving better care at a lower cost.

The Importance of Data in Driving Innovation in Medicare Payment

Physicians and other clinicians believe in data informed by evidence and are driven to improve their performance based on high quality data. Perhaps the biggest tool we can give physicians to drive care quality and cost savings is relevant, timely, transparent and actionable data about their patient populations—both clinical and financial. The current state of quality and performance measurement suffers from a few deficiencies. All too often, measures mandated by CMS and other payers are heterogeneous and do not accurately reflect the nature of an individual specialty or population of patients. For example, many of the CMS Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) measures are not necessarily broadly applicable to specialties such as oncology or orthopedic surgery, yet these are important specialties which play a significant role in both cost and quality. Expanded efforts to allow registries to qualify for PQRS are a good step, such as those proposed in the recent 2013 Proposed Physician Payment Rule, but must be accelerated to facilitate broader participation and deal with some of the boundaries of claims-based data. The same is true for stage one Meaningful Use Measures—they are essential to usher medicine into the technological age but are largely process measures and not necessarily relevant across health care disciplines. Stage Three Meaningful Use will potentially address outcomes in a more direct manner, but that is yet to be determined. Reporting back to clinicians must also be timely and actionable—this is a promising aspect of the CMMI Pioneer ACO program that is engaged in timely data feeds to clinicians. Receiving patient outcomes data even one to two months much less years later does no good.

An attempt to strengthen significant quality measurement has propelled clinical societies to develop quality improvement programs using unique, clinically vetted, peer-reviewed quality and performance measures. These programs are often completely self-funded, and voluntary from an implementation standpoint, yet have shown incredible promise as vehicles for uniform care improvement and cost reduction. Clinicians developing the measures draw clear lines around conflict of interest and transparency is of the utmost importance. The American Society of Clinical Oncology has developed and refined their Quality Oncology Practice Initiative (QOPI), a clinically approved high-performing set of oncology related practice quality and performance measures. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) has been a vanguard in developing registry-based quality metrics that have largely moved the profession from great variations in quality and cost to a model for others to follow. Cardiology is doing the same with the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR), a comprehensive, outcomes-based quality improvement program representing approximately 11 million patient records that can support quality improvement in patients undergoing cardiac catheterization. More examples can be found in other clinical disciplines; a payment system that acknowledges this important work can be paramount in ensuring that a transition from our current payment system to a broader vision can be done with high expectations around quality and measurement reporting.

Supplying Medicare data on these clinician-developed measures and creating a payment system based on performance on these measures over the long term will drive cost reductions and care improvements. Additionally, there are efficiencies of scale to be gained from promoting consistent measures that are developed, collected and reported in a more homogenous manner—practices having to juggle six to eight different quality reporting streams to achieve payment bonuses only exacerbates waste and the silos in health care.

We need to move to a system of quality and performance measurement and reporting that takes advantage of the leadership already shown by many primary care and specialty groups to define unique, clinically approved, appropriate measures; incentivize participation in reporting programs; and, ultimately, move over time to a payment system that rewards high performing providers on these issues and penalizes those who do not.

Moving Forward Now

The path forward is not easy but the opportunity cost of doing nothing is no longer tenable. I hope that I have illustrated that it is feasible to start moving now from payments based on FFS to payments that instead give providers more flexibility to improve the efficiency and quality of their own services, and also to support better coordination, with potential additional support and savings from overall system wide savings. These system wide savings have been well documented and are found in reductions in unnecessary care, administrative simplifications that allow for streamlined quality measurement and transitions in care, timely data reporting, and cost transparencies. It is important to note that while I have focused on examples led by physicians, these are interdisciplinary efforts that reflect the depth and breadth of a great deal of health professions, some of which face significant shortages and supply issues that are significantly affected by disparities in reimbursement.

Thank you again for allowing me to participate in this hearing today and I look forward to further dialogue on this issue.

[i] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Office of the Actuary, accessed July 14, 2012

[ii] Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating Waste in US Health Care. JAMA. 2012;307(14):1513-1516. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.362

[iii] Sprandio J. 2010. Oncology-Patient Centered Medical Home and Accountable Cancer Care. Community Oncology. 7(12):565-572

[iv] Referral and Consultation Communication Between Primary Care and Specialist Physicians: Finding Common Ground. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(1):56-65.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

TestimonyUsing Innovation to Reform Medicare Physician Payment

July 18, 2012