Chairman Baucus, Ranking Member Hatch and members of the Committee, thank you for this opportunity to highlight ways to advance physician payment reforms in Medicare. The Medicare program retains a strong commitment to provide care to approximately 50 million beneficiaries across the country; a key partner in the provision of this care are the 900,000 healthcare providers who see beneficiaries in medical offices, hospitals, skilled nursing facilities and other settings.[1] Each day, providers work hard to deliver the best care for their patients yet our current payment system falls short time and time again, with financing mechanisms that perpetuate fragmented care and volume over coordination and value. Fortunately, there are better ways to pay physicians that can enable them to improve care, enhance the patient experience and potentially achieve greater savings for the Medicare system overall. I am honored to present some solutions from my work at the Engelberg Center for Health Care Reform at the Brookings Institution and our Merkin Initiative on Clinical Leadership, as a Commissioner on the National Commission on Physician Payment Reform and perhaps most importantly, as a practicing internal medicine physician.[2]

Current Payment Policies in Medicare

Currently, Medicare pays physicians primarily by a fee-for-service (FFS) schedule that is informed by relative value units (RVUs). Relative value units are determined from the Resource Based Relative Value Scale (RBRVS) which defines the value of a service through a calculation of physician work, practice expense and practice liability.[3] A relative value unit is assigned to every medical service that physicians carry out during a clinical visit. [4] The RVU is then adjusted by geographic region (so a procedure performed in Miami, Florida is worth more than a procedure performed in Salem, Oregon). This value is then multiplied by a fixed conversion factor, which changes annually, to determine the amount of payment to the physician. As the number of billable service codes have grown over time, an extensive regulatory process was enacted to develop RVU weights and update them year over year.

Over time, the RVU updating system has placed an increasing importance, evidenced by RVU weights, on procedures, scans, and other technical services that fix certain ailments or problems. Emphasis on technologies and interventions have resulted in a marked disparity between reimbursement for specialties which emphasize procedures such as cardiology and gastroenterology and those that do not such as primary care, endocrinology or infectious diseases, thus exacerbating shortages and the hierarchical culture within medicine.

The 1997 Balanced Budget Act exacerbated the problem with the introduction of the sustainable growth rate or SGR. The SGR was intended to keep the growth in Medicare physician-related spending per beneficiary in line with growth in the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP). In the early years of the SGR, this worked fine, as spending growth was lower than the calculated GDP target and payment rates for physician services increased. But starting with the recession in 2002, spending growth per beneficiary began to exceed GDP growth. In 2002, payment rates were reduced accordingly, by 4.8 percent.

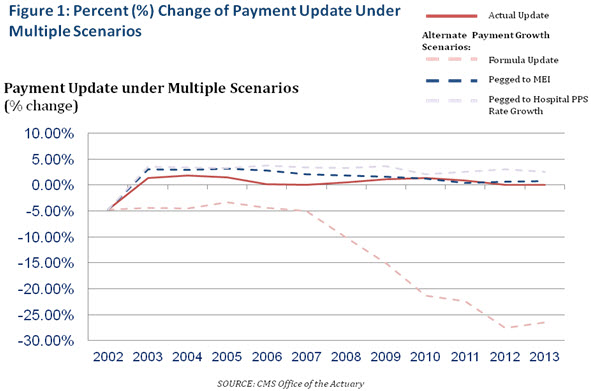

Every year since then, the scheduled SGR payment rate reductions have not taken full effect. Instead, because of concerns about access to care and the sufficiency of payments, Congress has headed off the full payment reductions on a short-term basis. Typically, this has involved offsetting at least some of the budgetary costs with payment reductions affecting other Medicare providers. As Figure 1 illustrates, actual updates as well as the SGR formula update still grow at rates far below input costs (MEI) and payment rates for other providers, thus exacerbating systemic flaws. In short, our system is broken.

Payment Reforms in the Affordable Care Act

The Affordable Care Act included over 100 policy changes in Medicare provider payments, many of which are currently being phased into the current delivery system and affect physicians directly. [5] These reforms include Medicare Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), Value-based payment modifiers, the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement initiative as well a number of broader efforts for statewide level innovation, multipayer efforts to promote primary care and alignment of payments for Medicare-Medicaid beneficiaries (dual eligibles). These reforms are incredibly effective at encouraging providers to delivery high-quality, coordinated care at a lower cost and enable Medicare to pay for value. As Jonathan Blum, Acting Deputy Administrator and Director of the Center for Medicare recently pointed out in his testimony before this committee, “the Medicare program has been transformed from a passive payer of services into an active purchaser of high-quality, affordable care.” [6] While these reforms will offer a great deal of insight into how we can improve Medicare physician payment through authorities granted in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, they are still largely based on a fee-for-service payment system. We must acknowledge the limitations in implementing payment reforms in the face of a dominant fee-for-service system. One early large-scale Medicare pilot implemented in oncology in 2006 serves as a good example: in conjunction with reductions in Part B drug payments, oncologists received an additional payment to report on whether the chemotherapy care provided by them adhered to certain evidence-based guidelines. This promoted comparisons to the published guidelines and also supported the development of evidence on how widely published guidelines were being followed in practice. [7] However this pilot did not make any changes in the underlying structure of fee-for-service payments and did not explicitly tie payments to measured improvements in performance, resulting in limited feasibility and adoption. In order to move away from our current system and build on the promise of ongoing efforts we must remove the SGR as a constant impediment to true systemic change.

Recommendations of the National Commission on Physician Payment Reform

In an effort to explore new ways that to pay for care that can yield better results for both payers and patients, the Society of General Internal Medicine convened the National Commission on Physician Payment Reform in 2012. Our commission, composed of a broad range of leadership and expertise spanning the public and private sectors, adopted twelve specific recommendations for reforming physician payment:

- The SGR adjustment should be eliminated

- The transition to an approach based on quality and value should start with the testing of new models of care over a 5-year time period and incorporating them into increasing numbers of practices, with the goal of broad adoption by the end of the decade.

- Cost-savings should come from within the Medicare program as a whole. Medicare should where possible, avoid cutting just physician payments to offset the cost of SGR repeal, but should also look for savings from reductions in inappropriate utilization of Medicare services.

- The Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC) should continue to make changes to become more representative of the medical profession as a whole and to make its decision-making more transparent. CMS has a statutory responsibility to ensure that the relative values it adopts are accurate and appropriate, and therefore it should develop alternative open, evidence-based, and expert processes beyond the recommendations of the RUC to validate the data and methods it uses to establish and update relative values.

- For both Medicare and private insurers, annual updates should be increased for evaluation and management codes, which are currently undervalued, and updates for procedural diagnosis codes, which are generally overvalued and thus create incentives for overuse, should be frozen for a period of three years. During this time period, efforts should continue to improve the accuracy of relative values, which may result in some increases as well as some decreases in payments for specific services.

- Fee-for-service contracts should always include a component of quality or outcome-based performance reimbursement.

- Higher payment for facility-based services that can be performed in a lower cost setting should be eliminated. Additionally, the payment mechanism for physicians should be transparent, and should reimburse physicians roughly equally for equivalent services.

- In practices having fewer than five providers, changes in fee-for-service reimbursement should encourage methods for the practices to form virtual relationships and thereby share resources to achieve higher quality care.

- Over time, payers should largely eliminate stand-alone fee-for-service payment to physicians because of its inherent inefficiencies and problematic financial incentives.

10. Because fee-for-service will remain an important mode of payment into the future even as the nation shifts to fixed-payment models, future models of physician payment should include appropriate elements of each. Thus, it will be necessary to continue recalibrating fee-for-service payments, even as the nation migrates away from that method of paying physicians.

11. As the nation moves from a fee-for-service system to one that pays physicians through fixed payments, initial payment reforms should focus on areas where significant potential exists for cost savings and higher quality.

12. Measures should be put into place to safeguard access to high quality care, assess the adequacy of risk-adjustment indicators, and promote strong physician commitment to patients.

Moving Beyond the SGR

Eliminating the SGR is a principal recommendation of many expert reports, including our Commission’s Report, MEDPAC, The Brookings Institution, Simpson-Bowles and the Bipartisan Policy Center, but the question remains, repeal and replace with what? [8][9],[10] As stated above we (and other clinical groups and societies) recommend a five year transition to newer models of payment which move away from FFS as the dominant payer. But the devil is in the details, and proposals to move towards new models over a period of time leaves policymakers and physicians wondering what their practices will look like next month, next year and beyond. In moving from principle to practice, it is also important to acknowledge that while there will be no one payment model that applies to all physicians, payment models must be relevant to primary care physicians and specialists alike. Additionally, given the growing complexity of caring for Medicare beneficiaries, payment models should encourage collaborations between specialists and primary care physicians rather than focus on a model that is suited for one clinical specialty alone.

Short-Term Steps in Advancing Payment Reforms

To facilitate providers’ transition to alternatives to fee-for-service payments, CMS should harmonize current payment adjustments and quality improvement initiatives and apply those funds towards a care coordination payment which could give physicians more support for broader long-term reform pathways. Medicare has implemented quality reporting systems and payment adjustments for physicians, hospitals, and other providers. But these payments are generally administered as either a flat percentage or adjuster to all FFS payments. In contrast, shifting some existing FFS payments into a care coordination payment would give providers more support in moving toward condition-based, episodic payments, or global payments that allow for management of a population of payments that would otherwise be impossible in the current payment setting.

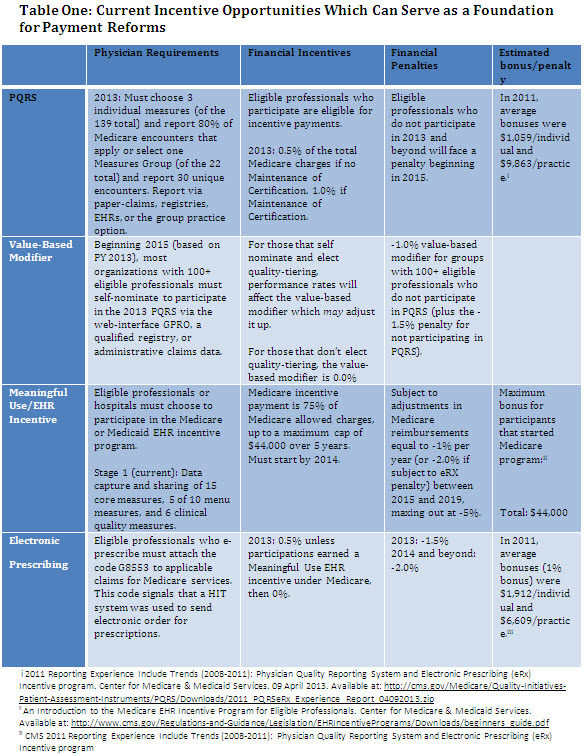

Table One highlights current efforts within the Medicare to increase value in care; each initiative is important but in isolation results in marginal financial gains and at times and each of these initiatives is limited in scope. For example, quality measures for the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) have flexible annual submission options, with qualification through registries, electronic health records etc. However, the program has suffered from criticism that measures are not as relevant to specialists. And at best, providers will gain approximately an average of $1059 for participation per year, which some might say is not worth the effort, even in a penalty phase of the program. With the passage of the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2013, a mechanism will be in place by 2014 for specialty specific efforts to satisfy CMS’ reporting requirements for PQRS, which will encourage higher specialist participation in quality improvement efforts and help align clinician-developed quality measures with CMS’ mandate to examine quality of patient care. Applying these measures to help physicians understand how registries can not only benefit their patients but lead to better predictability in a changing payment landscape will facilitate entry into pathways of reform.

Meaningful use measures are also quite detailed with important process metrics but physicians will likely also “perform to the measure” and may have difficulty going beyond unless there are linkages to payment reform. This is reflective of the sentiment that many providers express that they are constantly being asked to measure and perform, all while trying to see just as many patients in a day of work with little to no reward for doing less or changing workflows in order to reduce inappropriate utilization of resources. For example, proposed Stage 2 meaningful use measures include 17 core measures and six additional menu objectives from which a physician would choose at least three. This adds up to a total of 20 distinct actions that often involve all office staff. Rather than adding to these measures, CMS should consider how existing measure components could be applied to a payment update overall or a care coordination payment for the care of a patient with a chronic disease.

In the case of a care coordination payment, providers who opt to enter into a care coordination pathway in the first year can receive a lump sum of payment. This payment would be roughly equivalent to the potential bonus payments for all programs in table one. In return they would have to demonstrate that they are improving clinical practice and implementing outcomes-based clinical measures which are germane to their practice. In this example, a cardiologist would receive a population level care coordination payment derived from bonus payments and some FFS payments who does the following:

- Participates in a care coordination pathway for chronic cardiac disease (atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, etc)

- Subscribes to a cardiac specific registry (thus meeting PQRS requirements)

- Implements patient engagement tools for electronic care coordination, medication reminders, therapeutic lab monitoring for anticoagulation (meeting requirements for meaningful use, value-based modifier program, e-prescribing)

- Implements a significant practice transformation (potentially a new component which allows for a physician in a small, medium or large practice to individualize their approach to innovation)

The cardiologist would satisfy program requirements and would receive the maximum bonus payments.

Implementing this kind of approach involves potentially supporting CMS and additional entities to provide data on performance measures and quality improvement at more regular intervals along with technical assistance to understand how to translate incoming data into practice transformation. This process can begin in the year following a SGR repeal and can be supported through the assistance of existing clinical societies and quality improvement organizations. In this manner, assumption of clinical and performance risk becomes more commonplace for physicians. Simply put, physicians understand that they need to be held accountable for payment in a standard fashion, but want to feel that they can bring some degree of personalization into their practice in order to meet the needs of their populations.

Finally, I encourage CMS to continue implementing important changes through the Physician Fee Schedule including recent changes for care coordination.[11] These changes are an important acknowledgment that while we migrate from a payment system dominated by fee-for-service, we need to also enhance the existing system to be aligned with the expected outcomes of policy changes. Recent calls for evaluating the distribution of evaluation and management codes and determining the accuracy and appropriate valuation are also an important step in the short term.

Movement from The Short Term to Longer Term Sustainable Payment Reforms

As clinicians of all specialty types realize that there is a viable pathway to care for patients and work across silos. The appetite for a more attractive option is evidenced by the overwhelming response to applications for the CMMI Challenge Grants, BPCI initiative, Medicare Shared Savings Program and other efforts. Clearly, physicians want an alternative.

Through my work at the Brookings Institution’s Engelberg Center for Health Care Reform and the Richard Merkin Initiative on Clinical Leadership, we have been meeting with physicians in primary care and specialties as well as other healthcare stakeholders. With iterative feedback from clinicians in practice, we have proposed a longer term payment model that takes into account the currently uncompensated critical elements of patient care, the need for more flexibility in the way physicians are able to use their time and treatment resources in the best interest of their patients’ individual circumstances, and the need to implement care reforms in a way that recognizes the intense and growing cost pressures in our health care system.

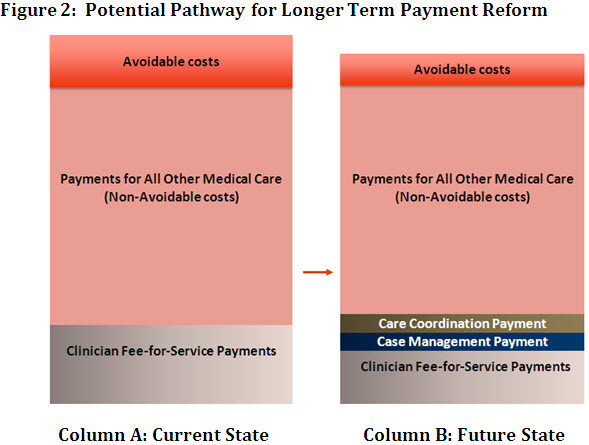

Our model, outlined in Figure 2, would build on the short term payment advances above with incorporation of a payment for care coordination that is derived from the programs in Table One and identify additional opportunities to improve care and lower costs that are not reimbursed well in traditional fee-for-service payment systems. For example, a common procedure in the outpatient cardiac practice is the echocardiogram (echo), or ultrasound of the heart. This procedure is sometimes performed in place of preventive counseling or watchful monitoring of a patient in coordination with a primary care physician, in large part because a hospital-based outpatient cardiology practice receives up to $450 for an echo compared to $53 for a visit without the procedure. Imagine paying both the cardiologist and primary care physician a fixed payment of $400 that allows for longer term communication and conservative monitoring in return for reporting on clinical outcomes at a population level. The clinicians are take the financial risk involved in the clinical care of their patient using the investments previously made by clinically driven pathways, registries and care coordination solutions.

Column A represents total spending on health care and reflects the current state of physician payment: exclusive reliance on the FFS model for physician payments, with waste and inefficiency in the form of redundant and unnecessary care, breakdowns in coordination, escalation of preventable complications etc. This leaves the total cost of physician care high.

Column B illustrates total spending in our alternative payment model. First, a set of services currently reimbursed for a particular episode of care or part of chronic care management are bundled together into a single payment to physicians as a case management payment. For example in clinical oncology a case management payment would include after hours phone care for breast cancer or a palliative care counselor for patients with lung cancer. This enables clinicians to focus less on volume and more on tighter coordination among providers and settings for patients. In addition, we continue the aforementioned care coordination payment paid to physicians, which is built on concepts such as PQRS/ MU and actually increases the current level of physician payment relative to the fee-for-service baseline in Column A. Care coordination payments allow flexibility for physicians to invest in clinical practices and infrastructure through practice transformations that maximizes their ability to treat patients in clinically appropriate ways while not reducing their income due to reductions in billable procedures that would otherwise occur. The investments in clinical practice can include infrastructure/HIT investments or in the case of a small practice, an investment in a shared clinical social worker with other small practices with similar patient populations.

Continuous quality improvement resulting from adherence to clinician-driven process and outcomes measures and the increased flexibility in income will push physicians to decrease and ultimately eliminate the waste and inefficiencies that plague the current system. Overall physician payments increases, offset by reductions in total Medicare spending and system wide savings. Care coordination payments that enhance total physician income tied to quality measures would encourage physicians to collaborate and focus on elements of patient care that reduce cost and inefficiencies across the spectrum. In oncology, for example, we do not specify which metrics should be used in which case but comment that target metrics would change over time and as efficiency is maximized in certain areas of care (i.e. ED visit rates) bonus payments would not cease because of lack of room for improvement. Measures would have to be selected with flexibility to accommodate various provider circumstances and changes in the long term improved performance in certain areas.

Physicians who enter into broader accountable care arrangements in which there is a shared savings component will likely find that this model could lead to an increased proportion of shared savings beyond the 2% threshold; therefore our described model would not be mutually exclusive to ACO arrangements, but could enhance them given the decreased reliance on fee-for-service reimbursement.

Tools that Enable Financial, Clinical and Performance Risk

As I have mentioned earlier, physicians will need tools to better understand risk- these are not lessons we had in medical school or in clinical training. Financial metrics (such as those available to ACOs), performance metrics in the form of actionable and regular data feeds as well as peer-led initiatives should be considered essential components of a payment reform package.

Conclusion

Our nation is in a sustained period of constrained finances and while the cost to repeal the SGR has been decreased to $138 billion, finding the offsets and mechanism to pay for such a solution will not be easy. But it is essential that this Committee seize the opportunity to finally dispel the notion that we allow for a system that rewards the balkanization of our patients through a payment mechanism which promotes volume over value. I commend Senators Baucus and Hatch in their recent call for proposals and specific suggestions from the clinical community and look forward to working with the Committee to identify a tangible path forward. Thank you for this opportunity and I look forward to your questions and comments.

[1] Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. http://www.medpac.gov/documents/Mar12_EntireReport.pdf

[2] Frist W, Schroeder S, et al. Report of The National Commission on Physician Payment Reform. The National Commission on Physician Payment Reform. http://physicianpaymentcommission.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/physician_payment_report.pdf

[3] The RBRVS has three components. Physician work accounts for the time, skill, physical effort, mental judgment and stress involved in providing a service and is approximately 48 percent of the relative value unit. Practice expense refers to the direct costs incurred by the physician and includes the cost of maintaining an office, staff and supplies and accounts for 48 percent. Professional liability insurance takes into account the malpractice insurance essential for maintaining a practice and is 4 percent of the calculation. Overview of the RBRVS. American Medical Association. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/solutions-managing-your-practice/coding-billing-insurance/medicare/the-resource-based-relative-value-scale/overview-of-rbrvs.page

[4]The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) uses Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes to determine services that it will reimburse for Medicare enrollees and each CPT code has an assigned relative value unit.

[5] Policy Options to Sustain Medicare for the Future. January 2013. Kaiser Family Foundation. http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/8402.pdf

[6] Statement of Jonathan Blum on Delivery System Reform: Progress Report from CMS Before the Senate Finance Committee. 28 February 2013. Full transcript available at: http://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/CMS%20Delivery%20System%20Reform%20Testimony%202.28.13%20(J.%20Blum).pdf

[7] Doherty J, Tanamor M, Feigert J, et al: Oncologists’ Experience in Reporting Cancer Staging and Guideline Adherence: Lessons from the 2006 Medicare Oncology Demonstration. J Oncol Pract. 6(2): 56–59. 2010.

[8] Antos J, Baicker K, McClellan M, et al. Bending the Curve: Person-Centered Health Care Reform. April 2013. Full report here: https://www.brookings.edu/research/reports/2013/04/person-centered-health-care-reform

[9] Bowles E, Simpson A, et al. A Bipartisan Path Forward to Securing America’s Future. Moment of Truth Project. April 2013. Full report available here: http://www.momentoftruthproject.org/sites/default/files/Full%20Plan%20of%20Securing%20America’s%20Future.pdf

[10] Daschle T, Domenici P, Frist W, Rivlin A, et al. A Bipartisan Rx for Patient-Centered Care and System-Wide Cost Containment. Bipartisan Policy Center. April 2013. Full report available here: http://bipartisanpolicy.org/sites/default/files/BPC%20Cost%20Containment%20Report.PDF

[11] Bindman A, Blum J, Kronick R. Medicare’s Transitional Care Payment — A Step toward the Medical Home.N Engl J Med 2013; 368:692-694

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

TestimonyAdvancing Reform: Medicare Physicians Payments

May 14, 2013