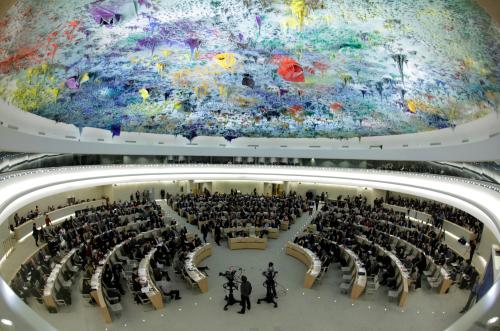

Ted Piccone testifies before the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations’ Subcommittee on Multilateral International Development, Multilateral Institutions, and International Economic, Energy, and Environmental Policy on the United Nations Human Rights Council. Read his full testimony below.

Good afternoon, Mr. Chairman, Senator Young and Mr. Ranking Member, Senator Merkley. I am grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the Subcommittee’s deliberations regarding the United Nations Human Rights Council and the role of U.S. engagement in supporting and strengthening the world’s only intergovernmental body devoted to human rights.

Since its establishment in 2006, the Human Rights Council has carried out its mission to promote universal respect for the protection of all human rights in a myriad of both traditional and innovative ways. These include public scrutiny of every country’s human rights performance in accordance with their international obligations; special sessions devoted to addressing gross and systematic violations in countries like Syria; fact-finding investigations; country visits by independent experts charged with monitoring issues ranging from violence against women to freedom of expression; and technical assistance and capacity-building. As a political body representing the United Nation’s highly diverse member states, it is both an invaluable instrument for human rights, and an imperfect one. The best option for making it better is for the United States to stay actively engaged in shaping and influencing its work.

As a close observer of its activities since its creation over a decade ago, I will highlight a few of the areas where the Council has made progress over the last several years, and where it has fallen short. I will then make some observations regarding the importance of strong U.S. leadership at the Council by comparing its performance before and after the U.S. joined the body.

Areas of Progress

- Universal Periodic Review: The Council has recently completed its second round of publicly examining the human rights record of every member of the United Nations. This unique mechanism allows, for the first time, an opportunity for any government to raise questions and make recommendations about any other government’s human rights behavior. It brings recommendations from UN treaty bodies, independent experts and civil society to the table for discussion in public hearings webcast around the world. The results so far are encouraging. Over time, more governments are making more action-oriented recommendations, and governments are accepting more of them.1 Notably, the five governments receiving the most UPR recommendations are among the most repressive in the world – Cuba, Iran, Egypt, North Korea and Vietnam. This process provides a key point of leverage for human rights defenders on the ground and internationally to hold governments accountable to their promises. It also universalizes and depoliticizes human rights as a core obligation of international law. This is a vast improvement on its predecessor, the Commission on Human Rights, which scrutinized only a fraction of UN member states during its existence and only with great effort and controversy. Systematic follow-up and implementation, along with tying human rights diplomacy and assistance to the most important recommendations, are needed to continue this progress.

- Country-specific Scrutiny: While the UPR is an important step in the right direction, it certainly is not enough to fulfill the Council’s mandate to address dire situations involving gross and systematic violations of human rights. To that end, the Council has dispatched more independent experts, known as special procedures, as well as fact-finding missions and commissions of inquiry to examine human rights abuses in some of the most urgent situations around the world. These include Iran, North Korea, Syria, Burundi, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Burma, Cambodia, Libya and Eritrea. Their reports provide authoritative findings on the complex patterns of violations, identification of responsible actors, and recommendations for accountability and reform. Between 2006 and 2015, the number of country-specific reports submitted by special procedures increased by 104 percent and the number of governments issuing standing invitations to these independent experts almost doubled to 114. Since 2006, the Council has convened 26 special sessions devoted to urgent cases of human rights, which one-third of the Council’s members can call at any time. These include two recent sessions on Syria and on South Sudan and one in 2014 on the atrocities committed by ISIS. Nonetheless, the Council has failed to act in the face of other urgent crises. To address this problem, the UNGA could allow the Secretary General, the High Commissioner for Human Rights, or the Security Council to request Council action on particularly urgent country situations.

- Commissions of Inquiry: The Council is establishing a growing number of commissions of inquiry to serve as independent fact-finding bodies to investigate grave violations of human rights, including crimes against humanity, and to identify perpetrators for the purpose of holding them accountable. This instrument is designed to document violations and victims quickly, before evidence is destroyed or witnesses lost, and to begin a process of accountability in situations where national authorities are unwilling or incapable of conducting proper investigations or trials. Since 2011, the Council has created 17 such commissions covering a diverse array of countries from Cote d’Ivoire to Sri Lanka.2 The commission on North Korea delivered a trailblazing 400-page report in 2014 documenting crimes against humanity – including murder, torture, rape, enslavement, forced abortions and knowingly causing prolonged starvation – carried out at the highest levels of government. The report triggered unprecedented attention by the UN Security Council, creation of a UN human rights field office in Seoul and, more recently, targeted sanctions by the U.S. government. The commission of inquiry on Syria, with support from a new supplemental body of experts recently established by the UN General Assembly, is preparing files on specific individuals responsible for massive human rights violations in that conflict so that, one day, there might be accountability for the victims under international criminal law.

- Access to Civil Society: The Human Rights Council is known as the most open and accessible body in the entire UN structure. This is precisely as it should be given that every human being is entitled to human rights under international law and deserves a chance to be heard. With the Council meeting three times a year in regular session, plus UPR and special sessions, side events, expert panels and a regular call for submissions from nongovernmental organizations, civil society has a special year-round place in the Council’s activities. With the support of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), the Council’s programs are ever more transparent through its website and webcasting facilities. Special rapporteurs routinely reach out to civil society activists and experts on their country missions, a key ingredient for ensuring their work is relevant to human rights defenders on the ground. UPR is also opening new doors for human rights activists to make their case directly to government officials for reforms that meet international standards and establishing systematic follow-up reviews.

Shortcomings and Options for Reform

1.Membership: The UN General Assembly is responsible for electing members to the Council based on “the contribution of candidates to the promotion and protection of human rights and their voluntary pledges and commitments made thereto.” In addition, once elected, members are charged with upholding “the highest standards in the promotion and protection of human rights” and “shall fully cooperate with the Council.”3 Sitting members that commit gross and systematic human rights violations can be suspended by the General Assembly. These criteria were intended to fix a recurring problem, which plagued the predecessor Commission on Human Rights, of members unwilling to honor or, worse, subverting the human rights promotion mission of the body. With the reallocation of seats geared more to Africa and Asia in 2006, these rules were also meant to guard against a predominant influence by non-democratic states uncommitted to the UN’s human rights pillar. Currently, about 45 percent of Council members are rated as free in Freedom House’s annual ratings and 23 percent are graded as not free.

Unfortunately, now with over ten years of experience, we can say that the membership results are disappointing. Time and again, member states elect candidates who do not meet the election criteria, even in the face of concrete evidence that they are not fully cooperating with the Council’s mechanisms. Even worse, states are unwilling to exercise the suspension option, as in the case of Burundi last year. Regional blocs too often put forward clean slates that give the General Assembly no real alternatives. We know that when slates are competitive, the UNGA has voted to deny seats to some of the world’s worst human rights performers; even Russia, a P-5 Security Council member, was defeated last November after its bombing of civilians in Aleppo, Syria. Thanks to competitive slates, other states have been defeated or chose to withdraw in the face of likely defeat, including Sudan, Iran, Syria, Azerbaijan and Belarus.

To address the membership problem, the United States and its democratic allies in the Community of Democracies should redouble their efforts to recruit other like-minded states to run, especially the many electoral democracies that have never sought a seat on the Council. They should build consensus in the GA for new rules that would mandate competitive slates for membership and lead by example in their own regional blocs. In cooperation with OHCHR, they should use the annual elections process as an opportunity to shine a bright light on the states that are not fully cooperating with the Council.4 Where regional slates are closed, the United States mission in New York should lead efforts to block the worst offenders from reaching the minimum 97 affirmative votes needed to be elected. Like-minded states should also increase their contributions to the Council’s special assistance fund established to help small island and low-income states fulfill the heavy demands of membership. Finally, in egregious cases, they should mobilize support to remove a state responsible for gross and systematic abuses, as in they did with Libya in 2011.

In the meantime, it is worth remembering that the Council continues to take robust action against states that commit grave violations, over the objections of members like China, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Burundi, Cuba and Venezuela. This is thanks to determined efforts by the United States and other like-minded governments to build cross-regional coalitions for action. When the Council adopts these measures by consensus – most recently this past March in the cases of South Sudan, Myanmar and North Korea – the moral and political voice of the Council is even stronger.

- Israel/Palestine: We can all agree that having Israel’s occupation of Palestine (OPT) as a permanent item on the Council’s agenda (Item 7) is patently biased and unfair. The annual ritual of singling out Israel for violations committed in the course of its five-decades long occupation of the Palestinian territories is hypocritical and violates the letter and spirit of the Council’s principles of “objectivity and non-selectivity.” It is long past time for moving Israel/OPT resolutions to the regular agenda item that deals with country situations, like any other country, and to reduce the number of Israel/OPT resolutions to a manageable and proportionate size. A serious negotiation should take place, perhaps led by the High Commissioner for Human Rights, with mediating support from states like Norway and Morocco, that would bring together Israel, Palestine and the Arab states for this purpose. The United States might help play a supporting role in brokering such an agreement as part of an early confidence-building step in an Arab/Israeli peace process. I agree, however, with the Council on Foreign Relations report published earlier this year that Congress should avoid conditioning its membership on the Council on eliminating Item 7 – it’s the wrong tool for the right goal.

- Protecting Human Rights Defenders from Reprisals: As noted previously, the Council’s mechanisms are the most open and accessible of any body at the United Nations. But several problems remain. NGO representatives invited to speak at the Council are too often interrupted with harassing points of order from repressive delegations. Reprisals against human rights defenders who cooperate with the Council are much too frequent. Any state found to be responsible for such reprisals, and which fails to rectify them, should be disqualified from sitting on the Council. Finally, the UN member states must fix the broken process of granting accreditation to civil society organizations. The UN NGO Committee in New York routinely has failed to discharge its duties in this regard and has become a tool for authoritarian states that fail to uphold basic norms of freedom of association in their own countries. If Congress wants to improve this situation, it should instruct our mission in New York to work with the Community of Democracies to lobby for a complete overhaul of the accreditation system to take it out of the hands of diplomats and give it to professional experts qualified to make the technical assessments needed to give civil society a greater voice at the United Nations.

U.S. Leadership

We know from years of experience in the field of human rights diplomacy that when the United States puts its shoulder to the wheel and adopts smart and constructive strategies to promote and protect human rights, it can succeed. We also know that when Washington decides to withdraw, as it did during the Council’s early years from 2006-09, the results can be disastrous for our interests and that of our allies.

During negotiations for creation of the Council, the Bush administration fought hard for a smaller body composed of strong human rights defenders and other reforms. When it did not achieve all its goals, the administration decided that the outcome was not worth their time and yielded the floor to the likes of Pakistan, Egypt, Algeria, Saudi Arabia, Cuba and others who were bent on manipulating the rules to castigate Israel and reduce scrutiny of other flagrant abusers. Unfortunately, they succeeded. During the U.S. absence, the Council indeed took action to make “the human rights situation in Palestine and other occupied Arab territories” a permanent agenda item. During the three-year period when we were absent, the Council’s members also convened no less than six special sessions on Israel’s behavior and established two commissions of inquiry on Israel’s record in the Gaza conflict and elsewhere. Beyond Israel, the Council in 2009 shamefully convened a special session on Sri Lanka’s bloody termination of its conflict with the Tamil National Liberation Front that ended up praising the government’s anti-terrorism record. It also terminated mandates of independent experts monitoring human rights violations in Cuba and Belarus.

In 2009, the Obama administration decided to rejoin the Council and devoted significant diplomatic efforts to address its shortcomings. The United States won reelection to a second three-year term in 2012 and after a mandatory year off rejoined the body this year. The impressive results of this activism are a tangible reminder that U.S. leadership does make a difference in advancing both our values and our interests.

To give a few examples, the number of special sessions called on Israel dropped from six during the three years before we joined the Council to one during our first two terms as a member; a similar decrease in the proportion of country resolutions and commissions of inquiry devoted to Israel occurred, along with a corresponding increase in attention to dire cases like Iran, North Korea and Syria. Israel now participates in the Western European regional bloc and in the Universal Periodic Review and relies heavily on the United States to defend it from biased scrutiny by boycotting item 7 sessions, voting against unfair resolutions and lobbying others to join them.

Since the U.S. became a member in late 2009, the Council has also undertaken the following actions:

- Re-established special procedures mandates for Belarus and Iran (the Iran mandate was terminated in 2002 after the United States lost a bid for a seat on the former Commission on Human Rights). The two special rapporteurs on Iran have filed hard-hitting reports on the woeful human rights situation there, most recently citing Iran’s extremely high rate of executions, constraints on an independent judiciary, violations of due process, women’s rights and systematic discrimination against religious minorities. The Belarus mandate remains the sole international monitoring mechanism on the country.

- Established a commission of inquiry on North Korea, a more intensive mechanism to address that country’s alarming human rights situation, by unanimous vote. The commission’s final report relied on over three hundred interviews and satellite imagery to document crimes against humanity and singled out Kim Jong-un for his responsibility in such violations as forced labor, sexual violence and persecution of Christians and other religious minorities. Despite objections from Russia and China, the Security Council agreed to elevate North Korea’s human rights situation to its regular agenda. This was a historic step, establishing the incontrovertible link between human rights and international peace and security, a point that Ambassador Nicki Haley made effectively during the recent U.S. Presidency of the Security Council.

- Mandated a special OHCHR investigation into issues of accountability and reconciliation in Sri Lanka that restored momentum to the movement to address the government’s shortcomings in this area. With the election of President Sirisena in 2015, who promised to restore the country’s international standing, Sri Lanka is more open to international human rights monitoring and assistance.

- Convened four special sessions on the crisis in Syria and, in August 2011, created a commission of inquiry that continues to document the atrocities of the main parties to the conflict that eventually can be used to hold the perpetrators accountable under international criminal law. The COI’s list of Syrian individuals and groups allegedly responsible for war crimes already is paving the way for judicial proceedings against foreign fighters in at least three European countries.

- Adopted important new norms and monitoring in such areas as: protecting freedom of association and assembly against the growing attacks on civil society and human rights defenders; preventing violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI); combating religious intolerance while protecting freedom of expression; and condemning for the first time governments that intentionally block or disrupt access to the Internet. The SOGI resolution also broke new ground in appointing an independent expert to conduct country visits to assess the status of LBGT rights, engage activists and governments and provide reports and recommendations to the Council and the General Assembly.

These are just some of the many concrete deliverables that, simply put, would not have been possible without sustained and creative leadership by the United States. As documented in detail in the Council on Foreign Relations report of January 2017, in every case summarized above, our diplomats worked publicly and behind the scenes to forge cross-regional coalitions, draft pathbreaking resolutions, engage and defend civil society, and make the case for why the international community can make a difference in protecting human rights on the ground. Key to this record of success was appointment and Senate confirmation of a U.S. Ambassador dedicated to the hard work of building coalitions, improving membership and speaking out for continued reforms. The evidence against U.S. withdrawal from the body is clear – its absence from the Council’s deliberations during the first three years of its existence led to serious setbacks on multiple fronts, including the body’s preponderant focus on Israel.

Conclusion

In the end, the United States faces a clear choice: between engaging strategically as a principled catalyst through the international human rights system, or withdrawing to its own corner and letting authoritarian states weaken and dismantle that system. There should be no doubt in anyone’s mind that they are ready and willing to do so. Promoting and protecting human rights is too important to our national interests to be left to the spoilers and the naysayers.

The Council, we should recall, is but one instrument in our repertoire of tools to advance human rights around the world. But as demonstrated by the examples above, and even with its faults, it remains the only global human rights body with the legitimacy and universality to extend fundamental principles of human dignity to every corner of the world. Working alongside the High Commissioner for Human Rights, who is doing a remarkable job in calling the world’s attention to the most serious human rights situation, and our dedicated corps of diplomats in Geneva, New York, Washington and abroad, the United States should stay actively engaged and build on the Council’s proven track record of progress. It deserves Congress’s continued support, now more than ever.

-

Footnotes

- In 2008, just 27 percent of all UPR recommendations were accepted; in 2014 this number rose to 69 percent. Ted Piccone and Naomi McMillen, “Country-specific Scrutiny at the United Nations Human Rights Council: More than Meets the Eye,” Brookings Institution Working Paper, May 2016, p. 9.

- Only two of these 17 were related to Israel/OPT.

- UNGA Res. 60/251.

- This could be done through an annual report on whether or not a state accepts country visits by Special Procedures and responds to their communications, submits timely reports to treaty bodies, and implements recommendations accepted from the UPR mechanism.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

TestimonyAssessing the United Nations Human Rights Council

May 25, 2017