Content from the Brookings Doha Center is now archived. In September 2021, after 14 years of impactful partnership, Brookings and the Brookings Doha Center announced that they were ending their affiliation. The Brookings Doha Center is now the Middle East Council on Global Affairs, a separate public policy institution based in Qatar.

Three years have passed since the conclusion of the latest military assault on the Gaza Strip. Most of the Palestinian enclave still lies in ruins. Many Gazans continue to lack permanent housing, living in shelters and other forms of temporary accommodation. An absence of basic infrastructure—electricity, clean water, sewage treatment, and waste management—has blighted the daily lives of Gaza’s 1.9 million citizens.1 While the reconstruction process trudges along, a lack of employment opportunities has left 42 percent of the total labor force unemployed, rising to 60 percent among Gaza’s youth.2 Gaza can barely sustain the lives of its current inhabitants. With an annual population growth of 2.4 percent, the situation in the Palestinian enclave is becoming increasingly grim as humanitarian and reconstruction efforts fail to expand.3

Meanwhile, the enduring Israeli siege and naval blockade of Gaza exacerbates these problems, closing Gaza off to the outside world. The conditions in Gaza amount to those of an outdoor prison—a collective punishment that adds to the despair and frustration that arises from the enduring Israeli occupation and the need for a political settlement to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. While a final status agreement for peace between the Israelis and Palestinians seems out of reach, the humanitarian problems posed by the substandard living conditions in Gaza require the attention of international actors associated with the peace process. If the living conditions in Gaza do not improve in the near future, the region will inevitably experience another round of conflict, more violent than the last.

This policy briefing examines the organization of the Gaza Reconstruction Mechanism (GRM)—the temporary tripartite agreement between the Palestinian Authority (PA), the Israeli government, and the United Nations (U.N.) that has governed the reconstruction of Gaza since the 2014 war. It will describe the failures of the GRM, arguing that it has not advanced the reconstruction of Gaza as originally intended. Instead, the GRM has not only hindered progress on reconstruction, but it has also institutionalized the Israeli blockade.

The authors will conclude with recommendations on how to dismantle and replace the GRM, while accounting for political shifts in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and changes in global attitudes toward post-conflict reconstruction projects. The briefing will also suggest ways to improve the quality of life for Gaza’s people. After all, despite the absence of a political solution to the conflict at large, the international community should not lose sight of resolving the humanitarian crisis that continues to affect the civilian population caught in the middle of an intractable political conflict.

Impediments to Reconstruction

Several factors account for the slow reconstruction of Gaza. The first is restricted access into and out of the territory, enforced by both Israeli and Egyptian authorities. The Coordination of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT), a unit of the Israeli Ministry of Defense, approves any construction or humanitarian convoys crossing into Gaza from two entry points: Kerem Shalom in the south for commercial goods and Erez in the north for people (see Figure I).4Egyptian authorities control access via the Rafah border crossing, which was only opened for 32 days in 2015, 44 days in 2016, and 10 non-consecutive days in 2017 (as of May).5 Due to these restrictions, humanitarian and construction supplies have not been arriving in the quantities essential to effectively rebuild Gaza and bolster the growth taking place in the territory.

Figure I: Map of Gaza with Crossing Points

Source: UNOCHA, 2016

The ongoing political rifts between Hamas—the de facto government in Gaza—on one hand, and the Fatah-led PA, Egypt, and Israel on the other, only exacerbates the problem. Both Egypt and Israel do not trust Hamas and continue to consider it a security threat. Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi has hinted that he would regularly open the Rafah border crossing if the PA were to provide security in Gaza instead of Hamas.6 This would not only allow for an increase in the amount of construction materials coming into Gaza, but it would also bring these goods at a cheaper cost, due to the lower tax duties placed on goods entering through Rafah, as opposed to the Israeli border crossings.7

Funding issues have also impeded reconstruction. Despite the high-level of enthusiasm expressed during the Cairo Conference in October 2014, where many of the numerous pledges were made to rebuild Gaza, much of the donations remain unfulfilled. Of the $5.4 billion pledged at the conference, over half was committed to reconstruction projects in Gaza—but only 51 percent had been disbursed as of December 31, 2016.8 The Arab states—Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates—made some of the largest pledges during the conference; however, the bloc is also behind the bulk of unfulfilled payments—87 percent of unfulfilled pledges are from the Gulf, and 78 percent of the Gulf’s pledges remain unfulfilled (see Table I).9

| Table I: Disbursement Status by Donor of Pledged Support to Gaza (USD Million) | |||

| Donor | Pledged Support to Gaza | Disbursement of Support to Gaza as of Dec 2016 | Disbursement Ratio of Support to Gaza |

| Bahrain | 6.5 | 5.15 | 79% |

| Kuwait | 200 | 48.93 | 24% |

| Qatar | 1,000 | 216.06 | 22% |

| Saudi Arabia | 500 | 90.41 | 18% |

| United Arab Emirates | 200 | 59.08 | 30% |

| GCC Total | 1,906.5 | 419.63 | 22% |

| Worldwide Total | 3,499 | 1796 | 51% |

Source: World Bank, 2016

Various factors explain the slow trickle of donor funding. For donors outside the Middle East, donor fatigue seems to represent one reason behind the slow disbursal. Donors appear to appreciate the severity of the humanitarian situation in Gaza, as demonstrated by the pledges made in Cairo. Despite this, a sense of futility took hold over some of the Western donors, as they saw their previous investments go up in the flames of war for the second, and in some cases, third time, making them apprehensive about providing further funding.

On the other hand, the Middle Eastern states that pledged donations to Gaza’s reconstruction have explicitly and implicitly demonstrated political positions that have reflected a polarization into two camps following the Arab Spring. On one level or another, Egypt, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE oppose Hamas, having expressed concern over the organization’s ties to the Muslim Brotherhood. Countries in opposition to Hamas do not want to send money to Gaza to avoid bolstering local support for the Islamist movement. They also rely on the assumption that slower reconstruction would erode Hamas’ legitimacy in the Strip, ultimately forcing a return to the political arrangements that preceded the organization’s 2007 unilateral takeover.

Meanwhile, Qatar and Turkey have delivered the two largest aid packages to Gaza out of all Middle Eastern countries ($216 and $139.48 million respectively). They have done so because of their close political ties to Hamas—having exhibited fewer reservations than their regional neighbors in providing assistance via Gaza’s de facto government. For example, in July 2016 Qatar contributed $30 million to pay the salaries of a considerable section of Gaza’s public servants, who were left without pay since 2013 because of a disagreement between the PA and Hamas.10 However, those generous deliveries are rare, and the shortage of donor funds continues to slow the reconstruction of Gaza. Since the World Bank released its pledge disbursal report in December 2016, funding did not see any increases.

In fact, barring a final political solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, donors will continue to reluctantly donate money to Gaza, a place that faces a perpetual cycle of destruction and reconstruction. Above all, a political settlement between the Israeli government and the Palestinians is the measure that would most dramatically improve the conditions in Gaza. However, with the creation of the most conservative Israeli governing coalition in the Jewish state’s history, a lack of political will on the part of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to negotiate with the Palestinians, and the intransigence of the PA and Hamas to form a unity government, a final settlement to end the decadeslong conflict seems like a fantasy.

What is the Gaza Reconstruction Mechanism?

Given these obstacles, the GRM was initiated in September 2014 in an attempt to reconstruct Gaza through a multi-tiered mechanism involving the Israeli government, the PA, and the U.N. At the time of the GRM’s inception, Robert Serry—the U.N. Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process (UNSCO)—promoted it as a means of coordination between the PA and the Israeli government to expedite reconstruction. It was instated to ease the flow of construction materials into Gaza by creating a direct line of communication between COGAT and the PA, with the U.N. serving as an intermediary between the two parties. During the GRM’s announcement, Serry argued that it would not only address Israeli security concerns, but it would also reinforce donor confidence, providing necessary funding for such reconstruction to take place.11

Through the GRM, an extensive system of inspection and monitoring of imports to Gaza was created. The theory behind this three-party arrangement was that by satisfying the security concerns of Israel, the U.N. and PA would speed up import of construction materials into Gaza, and as such help rebuild it in the aftermath of the destruction caused by the war, while simultaneously creating badly needed job opportunities for young Gazans in the private construction sector. UNSCO defined the GRM as a short-term arrangement, although it did not establish an end date for the mechanism.12 Acknowledging the unsustainability of the situation in Gaza, Serry remarked, “We consider this temporary mechanism [the GRM] an important step towards the objective of lifting all remaining closures.”13 On paper, the general objective of the GRM was “to enable construction and reconstruction work at the large scale now required in the Gaza Strip.”14 This aim was detailed in four corollary objectives:

(a) Enable the Government of Palestine to lead the reconstruction effort; (b) enable the Gazan private sector; (c) assure donors that their investments in construction work in Gaza will be implemented without delay; (d) address Israeli security concerns related to the use of construction and other “dual use” material.15

On the face of it, the GRM seemed like a positive outcome at the time, working in favor of all involved. However, many of those objectives were lost during implementation. It quickly became evident that the way the GRM was conceived gave Israel’s COGAT the final word over any construction project or construction materials entering Gaza. Thus, Israel’s security concerns were prioritized. Meanwhile, neither the PA nor Hamas were given much say over the rebuilding process and leadership by the “Government of Palestine” was minimized. In fact, the mechanism has failed even to address the third objective. Construction has proceeded at a slow pace and with many delays, which has discouraged donors from increasing the speed at which they disburse aid to Gaza.16

The purpose of establishing any political tool hinges upon creating a highly efficient and functioning system to reach a defined goal. In theory, that should be the primary purpose of the GRM. It should provide a clear channel of communication between COGAT, the PA, the U.N., and members of Gaza’s civil society to facilitate reconstruction projects in the Palestinian enclave. However, as the following sections will show, given the underlying causes of the conflict and the absence of political will to make the mechanism work as intended, the GRM ended up creating a cumbersome bureaucracy, which, after three years, represents at best, a system of conflict management, not resolution; and at worst, an institutionalization of the Israeli siege of Gaza.

Lagging Progress

The 2014 war caused a wide range of damages to 171,000 homes, ranging from minor damage to complete destruction. As Table II illustrates, the cost of repairs to these homes ranges from $5,000 or less to $35,000. 17 From the 171,000 affected homes, about 61,086 still need repairs or require new construction, but have not yet received confirmation for funding as of May 2017. In other words, more than a third of the affected homes still require work. Shelter Cluster estimates that the completion of reconstruction will not occur until August 2018, a year after the initial deadline.18

| Table II: Reconstruction Progress by Category and Average Cost (# of units, USD) | |||||

| Damage Level | Minor Damage | Major Damage | Severe Damage | Destroyed | Total |

| Damage Description | Windows and doors and small holes in external walls. | Damages are in part of the house and some parts are still inhabited. | Damages are in essential parts of the house. It is uninhabitable until major work takes place. | Destroyed or beyond repair. The housing unit needs demolition and reconstruction. | – |

| Average Cost of Reconstruction | Less than $5,000 | More than $5,000 | $10,000 to $18,000 | $35,000 | – |

| Number of Units | 147,500 | 5,700 | 6,800 | 11,000 | 171,000 |

| Completed | 84,308 | 1,794 | 6,768 | 4,274 | 97,144 |

| In Progress | 8,857 | 898 | 32 | 1,516 | 11,303 |

| Funded[19] | 0 | 58 | 0 | 1,409 | 1,467 |

| Remaining Units | 54,335 | 2,950 | 0 | 3,801 | 61,086 |

Source: Shelter Cluster Palestine

Nearly three years after the war in Gaza and two and a half years after the introduction of the GRM, the limited progress made in reconstruction has demonstrated the ineffectuality of the mechanism. According to a U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) report, “at the height of the 2014 war, nearly 500,000 people, 28 percent of the population, were displaced from their homes.” From the 16,000 families that were still displaced between August and December 2015, 62.5 percent claimed that they rented accommodation, and of that group, 50 percent feared eviction from their rented living quarters. As of April 2016, approximately 75,000 people were estimated to remain displaced.19 Those numbers demonstrate that displacement continues to be an issue and the GRM did not effectively expedite reconstruction.

A Labyrinth of Bureaucracy

A look at the approval process gives a glimpse into the large amount of bureaucracy created by the GRM, which partially explains the lag. Before a family in Gaza receives any construction materials, they must go through a multi-step process (see Figure II).20 First, the PA Ministry of Public Works and Housing (MoPWH) completes a survey of the damage to the homes. The assessment includes the amount of damage incurred, as well as the amount and type of building materials required for a particular reconstruction project. It then uploads the assessment to the joint COGAT, PA, and U.N. database established under the GRM. The PA submits the assessment to the High-Level Steering Team (HLST), comprised of representatives from COGAT, the PA, and the U.N. At this point, COGAT can either approve or veto the assessment. After the approval process, the HLST then provides the beneficiary with coupons, giving them permission to purchase construction materials from approved vendors. This authorization process must be completed for each step of construction—including laying a house’s foundation, framing, plastering, and finishing work.21Figure II: Gaza Reconstruction Mechanism Monitoring Streams

Source: GRM

Structural issues with the GRM arrangement complicate an already cumbersome process. The database, which governs the approval process, is run not by authorities in Gaza but by the PA in the West Bank, some 160 kilometers from the commercial good entry point at Kerem Shalom.22 Another one of the PA’s duties is to funnel money to construction efforts through the Ministry of Finance. This method was intended to ensure transparency while building the PA’s capacity but ended up contributing significantly to slowing down the rebuilding process. According to the GRM agreement, the duration between registering a beneficiary and their receiving approval to purchase aggregate, reinforcing bars, and cement (ABC), “shall be limited to two working days.”23 However, in actuality, the waiting period has often amounted to weeks, or even months after each stage of construction.24Lack of Local Ownership

Notably absent from the GRM arrangement were Hamas and Gaza’s civil society.25 In addition to contributing to the aforementioned delays, by not consulting with Gaza’s local communities, UNSCO effectively allowed the process of reconstruction to be non-inclusive—leaving the fate of Gaza’s communities up to people who do not have as great a stake in the rebuilding process. This has caused a crippling lack of communication between Gaza’s civil society and the three entities that developed the mechanism.

On a basic level, members of Gaza’s civil society were not consulted during the development of the GRM, nor were representatives from Hamas’s political wing. Thus, the needs of Gaza’s people did not receive appropriate consideration during the conception of the mechanism. Gazans were only consulted on the reconstruction effort after the conception of the GRM, so they had no choice but to accept a program developed without their consent. Only after the start of the GRM did the authorities associated with it conduct a survey assessing the damage and the needs of Gazans.

In fact, civil society groups in Gaza did not see the full text of the GRM agreement until over a year after its conception. These groups would probably have never seen the specifics of the agreement had they not demanded its publication by UNSCO.26 The only document on the GRM, published by UNSCO, was a fact sheet that summarized the procedures, without going over the finer points regarding the monitoring process.27

Thus, from the perspective of the people of Gaza, a group of outsiders concocted plans to rebuild the territory while lacking any knowledge of the actual needs of the local communities.

Institutionalizing a Siege

While Gazans have little ownership over the mechanism, the Israelis have too much. With the GRM in place, the Israelis can now point to the mechanism as a justification for controlling the goods that enter the Palestinian enclave. Due to the potential dual-use nature—civilian and military application—of some of the construction materials entering Gaza, the GRM was initially proposed to reassure Israel through instituting a “neutral” apparatus that would inspect all materials entering the territory. Although the GRM was successful in establishing an indirect line of communication between the Palestinians and Israelis to ease the flow of construction materials, in actuality, it institutionalized the Israeli blockade by giving the Israeli government the highest authority over the reconstruction process. In effect, the GRM has moved beyond being a confidence building measure, and transformed into a political tool in the hands of Israel.

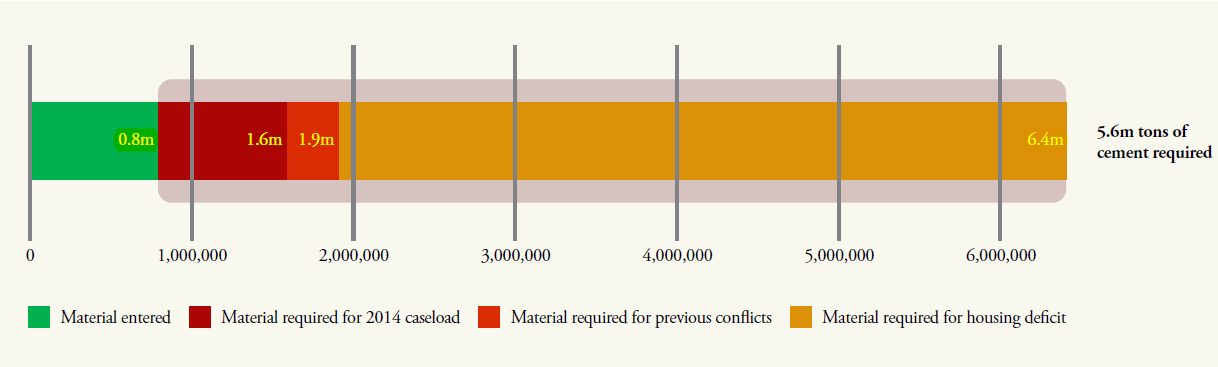

Even with the sophisticated system of inspection and monitoring of imports, COGAT still finds ways to further impede the reconstruction process. Despite expansions made to the Kerem Shalom crossing—the checkpoint where commercial goods enter Gaza—and the donation of a security scanner by the Dutch government, COGAT continues to devise new methods to slow the entrance of construction materials through the crossing.28 In May 2016, Israel imposed a 45-day ban on the import of cement, because it accused Hamas of hijacking deliveries.29 COGAT also banned the import of wood planks, which it accused Hamas of using to buttress its extensive network of tunnels.30 In terms of construction materials, cement and wood constitute basic elements required for the construction of homes, hospitals, and schools. Bans on the import of cement and lumber have significantly decreased the capacity for progress in Gaza’s reconstruction. Figure III displays the deficit of ABC materials required to complete the housing projects assessed by the MoPWH.31 The slow progress of construction projects proves that the continued blockade and control of movement imposed on Gaza by the Israeli government poses an exceptional obstruction to the improvement of the quality of life for Gaza’s residents.

Figure III: Cement and Rebar Entered vs. Required Quantity (Tonnes)

Source: Shelter Cluster Palestine, 2016

COGAT, by stating accusations without providing hard evidence continues to ban necessary construction materials from entering Gaza. The GRM could have been a shining example of joint Israeli-Palestinian cooperation, used as a framework for future collaborative projects, but instead COGAT found it suitable to abuse it. The purpose of the GRM was to share the responsibility of the reconstruction between different stakeholders in Gaza—including the Israelis—not leave it up to the party with the most power.

The Ripple Effect

Maher al-Tabbaa, a Gazan economist and a spokesperson for the local chamber of commerce, asserts that COGAT’s restrictions on material imports amount to “economic warfare.”32 Those policies have had sizeable effects on Gaza’s overall economy. For instance, the Strip’s well-established furniture manufacturing industry can no longer make furniture because it lacks the raw materials to do so. As a result, these companies significantly downsized their labor force, delivering another punishing blow to a community that already struggled with high unemployment.33

According to the U.N. Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), “over 80 percent of the people in Gaza depend on humanitarian assistance.”34 Another report by UNOCHA found that over 80 percent of displaced Gazan families have borrowed money to get by in the past year, over 85 percent purchased most of their food on credit, and over 40 percent have decreased their consumption of food.35 Although the GRM does not deal with the financial problems of Gaza’s residents, the figures provided by those studies do reveal one of its shortcomings. It did not create the job boom in the construction sector predicted by those who helped develop it. Clearly, more economic opportunities are needed in Gaza, and the ripple effect initiated by the GRM has been far from positive.

Recommendations

The absence of a long-term solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict leaves only one alternative to mitigate the suffering of Gaza’s people and prevent another cycle of war and destruction: to accelerate the speed of reconstruction. Noting the complications to reconstruction in Gaza created by the GRM, the blockade, and the Fatah-Hamas political deadlock, several actions could be taken to alleviate these problems.

After re-embarking on a path toward reconciliation between Fatah and Hamas, the dissolution of the GRM should take precedence in any effort to revive the reconstruction of Gaza. A new mechanism that sees a stronger role in monitoring for both Gaza’s civil society and the donor community could inspire confidence in the process and increase donor financial flows to the Strip. A greater focus on infrastructure projects would also ensure that the process generates maximum employment across Gaza.

Revive Reconciliation

The ongoing political deadlock in Palestinian politics guarantees the perpetual stagnation of Gaza’s reconstruction. Fatah and Hamas need to address each other’s economic and political grievances. Fortunately, an opening to reconcile Fatah and Hamas continues to grow, especially with the replacement of Khaled Mashaal—Hamas’s political chief—with former Prime Minister Ismail Haniyeh and the adoption of a new charter.36 The appointment of Haniyeh as Hamas’s political leader suggests that the organization looks to continue down a path of moderation, appeasing stakeholders in the region.37 These developments signal to Fatah that Hamas wishes to re-engage in reconciliation talks.

Cairo, which controls one of the key crossings into Gaza, should continue to mediate between the two Palestinian factions. However, in order for Egypt to serve as an effective mediator, el-Sissi must first reconcile with Hamas himself. Recent developments are signaling that this could soon be realized as well. Mohammed Dahlan—a former Fatah official despised by both Hamas and PA President Mahmoud Abbas—helped advance a reconciliation agreement between Egypt and Hamas.38 Under the agreement, Hamas has agreed to establish a buffer zone along its border with Egypt. In a move that signaled its own good will, Egypt sent fuel to Gaza in June 2017 to help alleviate the ongoing power crisis.39 As reconciliation between Egypt and Hamas moves forward, el-Sissi should leverage his restored relationship with Hamas to mediate between it and Fatah.

Dissolve the GRM

In the meantime, the GRM should be dissolved. It is time to give Gazans ownership over reconstruction, allowing them to participate in the development of an alternative reconstruction mechanism. As mentioned before, Gaza’s civil society and de facto government were not consulted during the GRM’s planning process. Therefore, the result of the agreement between COGAT, the PA, and the U.N. gave COGAT a disproportionate amount of power over the approval of construction materials. In addition to rearranging the power dynamics, empowering Gazan’s could also reduce costs and allow the U.N. to remove itself from a situation that greatly sullied its reputation as a thoughtful mediator in this conflict. An alternative mechanism could see a greater role for Gaza’s civil society in the monitoring of materials in conjunction with COGAT, while Hamas could be provided with greater responsibility over reconstruction, leaving them beholden to the satisfaction of Gaza’s citizens.

Yet, a few matters should be taken into consideration. Israeli security concerns regarding the dual-use of materials should not be discounted, but they should definitely be addressed in a more efficient manner. Monitoring the usage of the construction materials by the HLST should not necessarily stop, but there should be more of an effort on the PA side to communicate more openly with Hamas. This issue could be dealt with during the Fatah-Hamas reconciliation talks by stressing to Hamas the importance of cooperating with the reconstruction process. No materials should be diverted to reinforce tunnels or any other projects deemed hostile to either Fatah or Israel. This would be a tough sell to Hamas, but it would behoove Hamas to recognize the political capital it could gain by showing its willingness to cooperate in the reconstruction process.

Introduce Donor Monitors

A new mechanism to distribute reconstruction aid to Gazans will renew interest among international donors to fulfill their pledges. For instance, Kuwait, traditionally one of the more prolific donors to Gaza’s reconstruction, refused to fulfill its pledges because it recognized the inefficiency of the GRM.40 A positive change in the flow of reconstruction could resuscitate the supply of donor aid. International organizations involved in reconstruction should use the new mechanism to encourage the fulfillment of pledges made at the 2014 Cairo Conference. Additionally, regional actors should be encouraged to provide unilateral support to Gaza in an effort to expedite the reconstruction process. The Qatari unilateral model, although not perfect, seems to provide Gaza with better relief than the method provided by the GRM.41 Despite the recent Gulf crisis, Qatar recommitted its support to Gaza, diminishing the possibility of Hamas seeking patronage elsewhere, like Iran.42 Qatar’s envoy to Gaza, Mohammed al-Emadi, continues to visit Gaza to oversee the projects his government funds to help rebuild areas destroyed by the war.

Introducing a donor monitoring board is one way to further inspire confidence in donors, as it would give them a larger role in the reconstruction process.43 Previously, the GRM included a relatively small group of stakeholders in the reconstruction process. Allowing donors to monitor the projects through their own representatives would make them more comfortable with the reconstruction effort, inspiring them to fulfill their pledges. Gaza’s civil society should be tasked with developing this multi-party board of trustees to ensure that the needs of Gaza’s residents receive consideration. Regional donors that were not satisfied with the GRM should particularly be encouraged to participate. Countries that have either invested financially in the reconstruction process or expressed security concerns about it should be included in this board of stakeholders.

Focus on Infrastructure

To allow those funds to trickle down more effectively, the reconstruction effort should pivot toward infrastructure projects. According to an advisor with the Office of the Quartet, the reconstruction efforts were meant to not only rebuild Gaza, but also to provide Gazans with job opportunities during the reconstruction effort.44 Housing reconstruction efforts have failed to do this. Vanity projects like shopping malls and elaborate mosques may improve the morale of some of Gaza’s citizens, but those projects do not improve their lives in the long-term. Infrastructure projects, such as desalination plants, power stations, and road revitalization, are more likely to create long-term local jobs.

The reconciliation agreement that took place between Israel and Turkey last year provided a unique opportunity to make this a reality. Through the reconciliation deal, Israel agreed to allow Turkey to send tons of humanitarian aid through the Israeli port of Ashdod, circumventing the blockade imposed by the Israeli military.45 The arrangement allowed Turkey to contribute to numerous infrastructure projects, including the construction of a desalination plant, power station, and hospital.46 Construction materials for the hospital have recently arrived in Ashdod, en route to Gaza.47 Those efforts will allow Gazans to not only rebuild their homes, but also to find jobs that, at the very least, can temporarily provide them with the means to support their families.

Conclusion

Opening up to alternatives through the empowerment of fresh, local perspectives is the only way to revive the reconstruction of Gaza. These new possibilities will never realize their potential if the U.N. and other stakeholders—Israel included—do not consider the repeal of the GRM. Denying Gazans the chance to improve their own lives will make Gaza even more like a prison, and as the U.N. report on Gaza concluded, “The daily lives of Gazans in 2020 will be worse than they are now.”[49] What that would look like is unfathomable, because Gaza is already uninhabitable today. If such a political breakthrough materializes, years of restrictions placed on Gaza could diminish. Construction materials and employment opportunities would return to this once thriving community. On the other hand, sustaining the status quo in Gaza will mark another failure in the history of humanitarian aid, calling into question the utility and purpose of international aid organizations.

-

Footnotes

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), “The Gaza Strip: The Humanitarian Impact of the Blockade,” November 14, 2016, https://www.ochaopt.org/content/gaza-strip-humanitarian-impact-blockade-november-2016.

- Ibid.

- Central Intelligence Agency, “Gaza Strip,” World Factbook, July 25, 2016, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/gz.html.

- UNOCHA, “The Gaza Strip.”

- UNOCHA, “Gaza Crossings’ Operation Status: Monthly Update-April 2017,” May 17, 2017, https://www.ochaopt.org/content/gaza-crossings-operations-status-monthly-update-april-2017.

- Initially, the aim was to replace the Hamas security forces at the border, but it seems that Egypt was eventually willing to accept Hamas security at the border with PA support/collaboration. Rasha Abou Jalal, “Egypt Announces Deal to Open Rafah Crossing, But When Will It Actually Open?” al-Monitor, November 26, 2015, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2015/11/egypt-pa-deal-rafah-crossing-open-hamas-opposition.html.

- Quartet official, interview with authors, Doha, Qatar, February 23, 2016.

- Michael R. Gordon, “Conference Pledges $5.4 Billion to Rebuild Gaza Strip,” New York Times, October 12, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/13/world/middleeast/us-pledges-212-million-in-new-aid-for-gaza.html; The World Bank, “Reconstructing Gaza—Donor Pledges,” December 31, 2016, http://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/rebuilding-gaza-donor-pledges#4.

- Ibid.

- Reuters, “Qatar Says Gives $30 Million to Pay Gaza Public Sector Workers,” July 22, 2016, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-palestinians-gaza-qatar-idUSKCN1021AQ.

- U.N. News Centre, “Middle East: U.N. Envoy Announces Deal on Reconstruction in Gaza,” September 16, 2014, http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=48730#.V2pUufl96Uk.

- UNSCO, “Gaza Reconstruction Mechanism,” October 2014, 6, http://www.aidwatch.ps/sites/default/files/resource-field_media/gaza_reconstruction_mechanism_full-text.pdf.

- Robert Serry, “Briefing to the Security Council on the Situation in the Middle East,” UNSCO, September 16, 2014, 3, http://www.unsco.org/Documents/Statements/MSCB/2008/Security%20Council%20Briefing%20-%2016%20September%202014.pdf.

- Office of the Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process, “Gaza Reconstruction Mechanism Fact Sheet,” UNSCO, October 20, 2014, 1, http://www.unsco.org/Gaza%20Reconstruction%20Mechanism%20Fact%20Sheet%209%20October%202014.pdf.

- Ibid.

- United Nations, “Security Council Briefing on the Situation in the Middle East,” May 25, 2016, http://www.un.org/undpa/en/speeches-statements/25052016/middle-east; The World Bank, “Reconstructing Gaza.”

- Shelter Cluster Palestine, “Key Figures (May 2017),” June 12, 2017, http://www.shelterpalestine.org/Upload/Doc/b6072f7d-f789-4a14-8f37-cb3f70d46614.pdf; Shelter Cluster Palestine, “Gaza Reconstruction Mechanism – How to Engage? (Version 3)” July 31, 2015, 8, http://shelterpalestine.org/Upload/Doc/b9b914b2-d2a7-4885-a7b2-df42cef23b91.pdf.

- Ibid. This estimate is based off the assumption that all pledges will be met. Given the slow trickle of donor funds, this projected completion seems unlikely.

- UNOCHA, “Gaza: Internally Displaced Persons,” April 2016, 1, https://www.ochaopt.org/content/gaza-internally-displaced-persons-april-2016.

- The Gaza Reconstruction Mechanism, “An Agreement between the Government of Palestine (GOP) and the Government of Israel (GOI),” accessed July 16, 2017, http://grm.report/.

- UNSCO, “Gaza Reconstruction Mechanism,” 2; Member of Gaza civil society, interview with the authors, Doha, Qatar, January 20, 2016.

- IRIN News, “What’s in the U.N.’s New Gaza Agreement?” September 19, 2014, http://www.irinnews.org/analysis/2014/09/19/whats-uns-new-gaza-agreement.

- UNSCO, “Gaza Reconstruction Mechanism,” 3.

- Shlomi Eldar, “Why Young Gazans Need Cement to Get Married,” Al-Monitor, December 3, 2015, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2015/12/israel-gaza-cement-housing-shortage-youngsters-tunnels.html.

- Middle East Monitor, “Hamas: ‘We Have Alternatives Should Reconstruction Fail,’” November 26, 2014, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20141126-hamas-we-have-alternatives-should-reconstruction-fail.

- Palestinian Civil Society Organizations, “Letter to UNSCO,” November 26, 2015, http://www.ewash.org/news/letter-unsco.

- UNSCO, “Gaza Reconstruction Mechanism Fact Sheet.”

- Associated Press and Times of Israel Staff, “New Scanner at Gaza Crossing to Speed Rebuilding Effort,” Times of Israel, July 16, 2015, http://www.timesofisrael.com/new-scanner-at-gaza-crossing-to-speed-rebuilding-efforts/.

- Nidal al-Mughrabi, “Israel Resumes Cement Shipments for Private Gaza Reconstruction After 45-Day Break,” Reuters, May 24, 2016, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-israel-palestinians-cement-idUSKCN0YE11R.

- Jeffrey Heller, “Israel Cuts Back Gaza’s Lumber Imports – Palestinians,” Reuters, April 6, 2015, http://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-israel-palestinians-gaza-idUKKBN0MX0SJ20150406.

- Shelter Cluster Palestine, “Key Facts (May 2016),” June 8, 2016, http://shelterpalestine.org/Upload/Doc/16e94567-472e-4675-8c50-e69b32f055da.pdf.

- Heller, “Israel Cuts Back Gaza’s Lumber Imports.”

- “Marketing of Furniture from Gaza in Israel Permitted—Wood to Make the Furniture is Not,” Gisha Legal Center for the Freedom of Movement, November 2, 2015, http://gisha.org/en-blog/2015/11/02/marketing-of-furniture-from-gaza-in-israel-permitted-wood-to-the-make-the-furniture-is-not/.

- UNRWA, “Gaza Situation Report 149,” June 23, 2016, http://www.unrwa.org/newsroom/emergency-reports/gaza-situation-report-149.

- UNOCHA, “Gaza: Internally Displaced Persons,” 1.

- Beverley Milton-Edwards, “Head-hunting for Hamas,” Markaz (blog), Brookings Institution, October 12, 2016, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/markaz/2016/10/12/head-hunting-for-hamas/.

- Joshua Mitnick and Rushdi Abualouf, “Hamas Selects Popular Gaza Politician Ismail Haniyeh as its New Leader,” Los Angeles Times, May 6, 2017, http://www.latimes.com/world/middleeast/la-fg-hamas-leader-haniyeh-20170506-story.html.

- Dylan Collins, “Will Mohammed Dahlan Return to Lead Gaza?” Al-Jazeera, July 10, 2017, http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2017/07/mohammed-dahlan-return-lead-gaza-170709143522193.html; Peter Beaumont, “Hamas Seeks Help from Palestinian Foe to Relieve Pressure on Gaza,” The Guardian, July 9, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jul/09/hamas-seeks-help-from-palestinian-foe-to-relieve-pressure-on-gaza.

- Jack Khoury, “Gaza Electricity Worsens: Only Generating Plant and Power Lines from Egypt Shut Down,” Haaretz, July 13, 2017, http://www.haaretz.com/middle-east-news/palestinians/1.801075.

- Member of Gaza civil society, interview.

- Khaled Abu Amer, “Qatar’s Lifeline to Gaza,” Al-Monitor, April 3, 2017, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2017/03/palestine-qatar-reconstruction-committee-gaza-consensus.html.

- “Qatar Envoy to Gaza Pledges Continued Support,” Al-Jazeera, July 10, 2017, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/07/qatar-envoy-gaza-pledges-continued-support-170710070251325.html.

- Member of Gaza civil society, interview.

- Shahla, interview.

- Orr Hirschauge, Ned Levin, and Ayla Albayrak, “Israel and Turkey to Restore Full Diplomatic Ties,” Wall Street Journal, June 26, 2016, http://www.wsj.com/articles/israel-and-turkey-to-restore-full-diplomatic-ties-1466965042.

- Barak Ravid, “Israel and Turkey Officially Announce Rapprochement Deal, Ending Diplomatic Crisis,” Haaretz, June 27, 2016, http://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/1.727369.

- “Materials for Building Turkish Hospital, Reached Ashdod, will Arrive Soon in Gaza, Haniyeh says,” Daily Sabah, July 5, 2017, https://www.dailysabah.com/mideast/2017/07/05/materials-for-building-turkish-hospital-reached-ashdod-will-soon-arrive-in-gaza-haniyeh-says.