The June 2012 executive action announced by the Obama administration to provide temporary protection from deportation for unauthorized immigrants who arrived as children has required a host of civil society and government actors to implement.

The June 2012 executive action announced by the Obama administration to provide temporary protection from deportation for unauthorized immigrants who arrived as children has required a host of civil society and government actors to implement.

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) offers work authorization in addition to two-year protection from deportation for unauthorized immigrants under age 31 who arrived in the United States before their 16th birthday and before June 16, 2007. The relevance of this program is significant in light of the November 2014 announcement of the expansion of the program to three years for unauthorized immigrants of any age who arrived before their 16th birthday and before 2010. In addition, a new deferred executive action program, known as DAPA, for unauthorized immigrants who are parents of U.S. citizens or legal permanent residents was also introduced. The DACA expansion and implementation of DAPA have been suspended by a federal court.

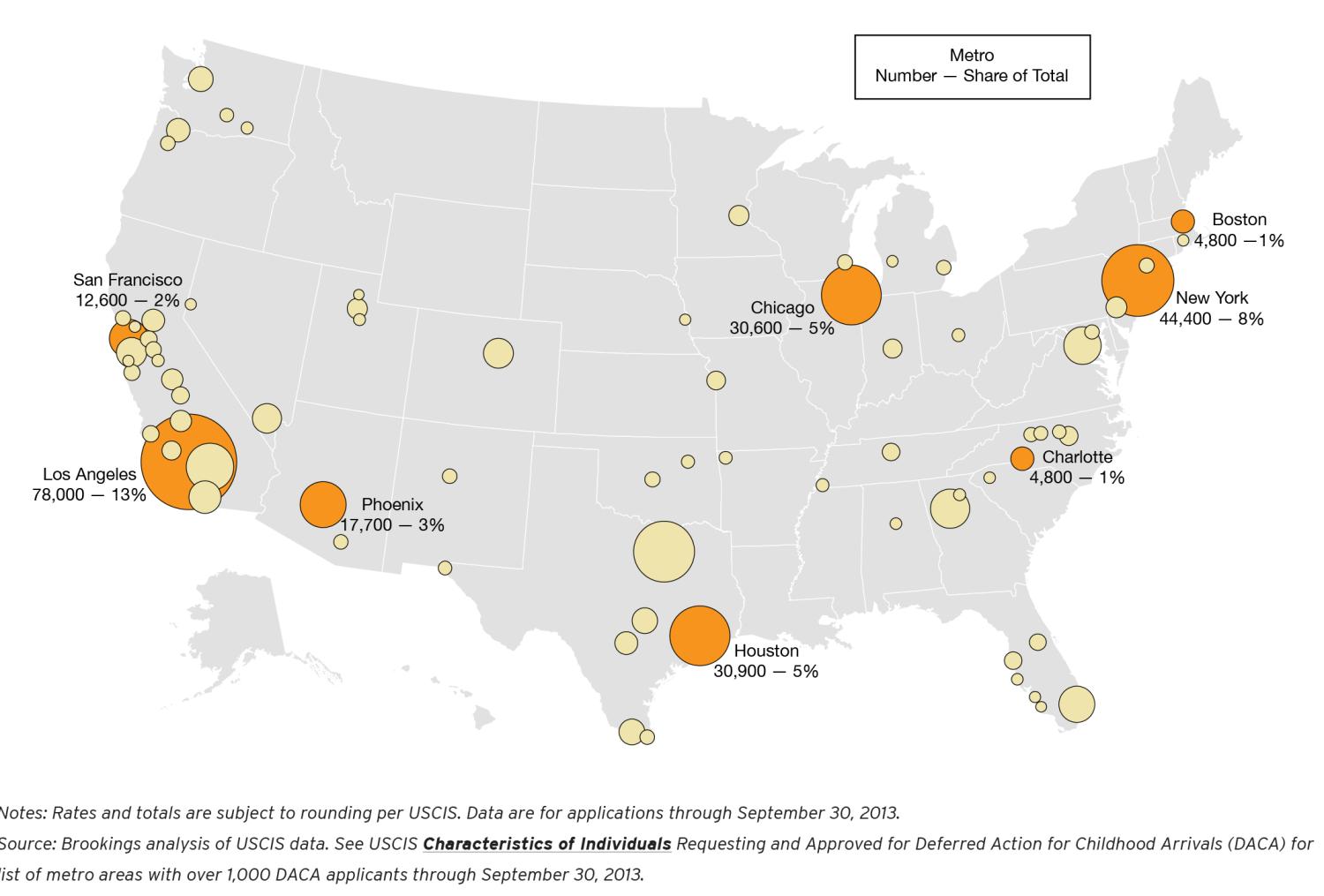

This study examines the implementation of DACA to understand application activity among young immigrants who are eligible for the program. It uses data from the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services agency (USCIS) and draws on interviews with immigrant service providers, advocates, and local governments in eight metropolitan areas (Boston, Chicago, Charlotte, Houston, Los Angeles, New York, Phoenix, and San Francisco). It finds:

Although DACA is a federal program, it requires civil society intermediaries and state and local governments for implementation. Nothing in the executive action gave an explicit role or funding to intermediaries, but they ramped up services quickly. In the initial months of the program, hundreds of thousands of people applied, and civic and immigrant support organizations, state and local governments, and foreign governments responded to requests for information and assistance, documentation to prove identity and continuous residence in the U.S., and legal advice. The federal government provided information about the program and reviewed and adjudicated applications, but it must rely on this range of intermediaries to ensure the program’s success.

Local contexts shape the DACA experience. The organizations that assist immigrants operate in a context shaped by the history of immigration, the resulting immigrant-integration infrastructure, and state and local policies ranging from those supporting the integration of immigrants to those seeking to deter unauthorized immigration through local enforcement or denial of services. The varying contexts in this study’s eight metro areas affect the funding and services that support the DACA-eligible population and ultimately influence immigrants’ decisions about applying. In places with a longer history of receiving immigrants, individuals may decide that the cost and risk of applying are not worth it if they are already able to work and live without constant fear of deportation. In locations with stricter enforcement mechanisms, the eligible population has a greater motivation to apply.

Perceptions of the DACA-eligible population shifted as key stakeholders learned on the job. DACA grew out of years of advocacy for the DREAM Act, which was focused on those who were pursuing postsecondary education (or military service), and DREAMer organizations took the lead on DACA implementation in many places. Also, many organizations that work with Mexican and Central American immigrants were particularly plugged into advocacy around the DREAM movement. Thus, focus was trained on young adults, especially those of college age, and those from Mexico, Central America, and other parts of Latin America. But the DACA-eligible group is from a more diverse set of countries and includes those younger than the college-age immigrants associated with DREAMers. By the end of the first year, service providers and advocates expanded their focus to more actively reach those who needed to obtain the educational credential (high school equivalency) to qualify, those from non-Spanish-speaking origins, those living outside of urban centers, and those who did not see themselves as potential applicants yet who qualified.

The decision to apply is influenced by individual, family, and immigrant origin-community dynamics. The DACA application decision is laced with opportunity, risk, and obstacles. It is both an individual one and one shaped by family and origin-community dynamics. Three factors stand out as having the greatest impact on DACA outcomes: age, educational attainment, and country of birth. In addition, gender, status at arrival, and the application fee were important factors that influence outcomes.

Insights from the implementation and administration of the DACA program are useful as cities, suburbs, towns, and rural areas turn their attention toward new policies that address the legal status of unauthorized adults. We offer several ideas to strengthen the DACA process and prepare for DAPA:

- Engage the hard-to-reach population.

- Prepare for requests for documents and provide support for applicants.

- Reinforce that DACA is an ongoing program, and that renewals are important.

- Reach employers and employees with information about work authorization.

- Maintain strong communication channels between USCIS and practitioners, advocates, and applicants.

- Build on DACA to make connections to educational, language, and employment supports.

DACA and DAPA are ultimately integration programs. They remove the fear of deportation and family separation and facilitate access to jobs, helping local communities and economies. But since they are temporary and can be ended at any time, Congress must use the experience to design a program that offers permanent legal status to immigrants who are already on their way to being productive members of the communities in which they live. The experience of implementing DACA offers valuable lessons for such future initiatives.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).