The struggle against global poverty may be about to get an important boost from an unexpected quarter. All too often, well-intentioned development programs have been undermined in the past by inefficiency, wrong-headed priorities, and outright graft. It is crucial to enhance the effectiveness of developing countries’ public spending on social goals. The public sector, however, cannot, in general, be relied upon to reform itself in isolation. The pressure of informed domestic public opinion is a crucial stimulus.

A key missing ingredient is a strengthened role for independent watchdog groups, home-grown within developing countries, and ferociously committed to opening up government budgets and policies for public review and discussion. Part think tank and part advocacy war-room, an emerging new breed of non-governmental organizations, free from special interests, has the potential in the years ahead to promote (and take advantage of) greater transparency and accountability in how developing countries operate, share information, and interact with their citizenry.

The impact of these groups, together with parallel efforts by governments and development assistance channels to clean up their own acts, could lead to better performing governments – and better informed citizens who are more able to use their voice and vote to bring to light, and cut short, public sector missteps.

Making this happen, though, will require support – financial and other – from key actors in the international community, spurred by leaders among the donors and foundations, to help watchdog groups build up their capacity from the fragile state that most of them, starved for funding, are in now. Promising pilots have shown that rapid “scaling up” is the right next priority. The groups’ needs include not just more core support to build and sustain stronger teams, but also requirements like training and technical assistance, and cross-country networking so they can learn from each other.

Policy Brief #157

Background

Five years after their adoption, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) have brought new attention to the challenge of extreme poverty and ill-health in the world’s less-developed countries. However, a third of the way to the MDGs’ target date of 2015, studies of progress reveal a mixed picture. While global poverty rates have fallen, especially in Asia, millions in sub-Saharan Africa are getting poorer, and in many other areas poverty rates are hardly budging. Education and health pose enormous challenges in most of sub-Saharan Africa and much of South Asia.

Narrowing these gaps requires intensified efforts. The UN and the World Bank have called for additional aid resources (studies have suggested an additional $60-150 billion might be needed ). However, few expect imminent boosts to official development aid — currently estimated at $78.6 billion (2004) — on this scale.

Beyond the quantity of development spending, increasing focus is now being given to issues of quality. At recent international meetings, development leaders have recognized the critical importance of effective resource use. These leaders have pledged themselves to reform the delivery and management of development resources.

In many developed countries, public accountability is much enhanced by independent work on public spending conducted by think tanks and similar groups. By contrast, developing countries are largely missing local capacity, independent of governments, to review public expenditures in a serious way. If credible domestic groups can be aided to develop this capability, they can promote greater transparency and foster informed public pressure for more effective and equitable public programs. This, in turn, can contribute to achieving fundamental social goals like the MDGs.

Bilateral donors, multilateral organizations, and external NGOs have begun to support greater fiscal accountability in developing countries. Promising pilot schemes now need to be scaled up, with additional resources to build the capacity of credible Civil Society Organizations (CSOs), and develop cross-country networks to share lessons of experience.

The Importance of Efficient Use of Public Resources

Effective utilization of public resources is critical to meeting development goals. Key programs in education and health are overwhelmingly conducted within the public sector. And although private provision of infrastructure has expanded in areas like telecommunications and energy, private investors remain wary of socially-oriented sectors such as water and sanitation, and also show little willingness to invest in the poorest countries.

At present, though, research indicates that increases in public spending are only weakly correlated with the achievement of development outcomes in most developing countries. Government ineffectiveness — in the form of waste, inefficiency and corruption — is largely responsible.

Poor resource usage is due in part to the fact that public spending is a complex, multifaceted process, which is not naturally transparent to the general public. Budgets typically pass through a sequence of stages, including formulation by ministries, scrutiny by legislative committees, approval by the legislature, distribution of funds to ministries, further distribution to state and local authorities, and end-point delivery. Accountability is hampered by deficiencies that include closed-door discussions, limited documentation, and poor data reliability.

Weakly-performing public institutions, in turn, can seldom be expected to reform themselves in the absence of external pressure. Unlike private companies, public bodies face no direct competitive pressures, and political systems – especially in developing countries – are often inadequate at mobilizing public pressure for specific institutional reform.

Weaknesses in public finance management can contribute to ineffective resource use through a number of channels. Corruption can often take a significant toll, but even in countries where government personnel are mostly honest, they can be hobbled by poor systems, inadequate training, or other deficiencies. Wherever allocation decisions are taken outside informed independent scrutiny, society’s more powerful and articulate groups tend to sway those decisions – to favor urban areas over rural, middle-class subsidies over pro-poor programs, and certain ethnic/cultural groups over others.

Case studies illustrate additional ways that poor governance hinders effective resource use:

- Studies in Bangladesh and India have demonstrated that the poor often do not receive the expected level of public services. An important part of the problem is heavy absentee rates among service providers, who typically lack adequate incentives to perform their assigned functions effectively; and

A recent study suggests that reducing average corruption levels in infrastructure projects in Latin America to the level of its best performer, Costa Rica, could reduce the average country’s operating costs in electricity by 23 percent.

The quantitative impact from significant improvements in public budget performance could be significant. Government consumption expenditures in low- and middle-income countries reached some $1,017 billion in 2003 (typically ranging from 15 to 45 percent of GDP). While quantitative estimates of overall waste, inefficiency, and corruption are speculative, even if as little as 5 percent of public funds constituted a recoverable loss, the ensuing $50 billion savings could substantially boost resources in areas like education, health and infrastructure.

Assessing Fiscal Transparency

Studies confirm that the public availability of accurate, timely information on public sector spending varies enormously across countries. Recent work at the IMF has developed operational measures of fiscal transparency, drawing on data from country-level studies known as Reports on Observation of Standards and Codes (ROSCs). An index of fiscal transparency has been prepared based on assessments of country adherence to best-practice in four areas:

- Data assurance: i.e., safeguards to ensure credible and reliable published data;

- Medium-term budgeting framework: efforts to place annual data in a multi-year context;

- Budget execution: e.g., the quality of accounting and auditing safeguards; and,

- The public disclosure of fiscal risks.

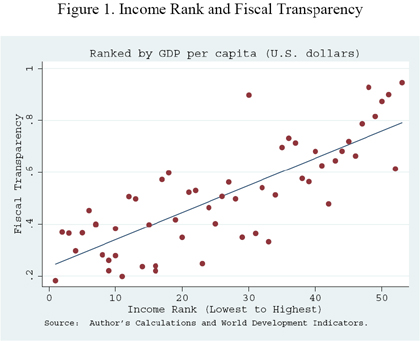

As shown in Figure 1, fiscal transparency based on this index is correlated with the level of overall development – in general, advanced countries do a better job of sharing accurate budget information with their citizens than less-developed countries.

Source: Hameed Farhan “Fiscal Transparency and Economic Outcomes,” IMF Working Paper 05-225 (December 2005)

Far from supporting the argument sometimes made that countries should just wait passively for economic development to bring improvements in public financial transparency in its wake, however, the research reinforces the importance of national efforts to improve levels of fiscal transparency:

- After controlling for the level of development, countries with higher fiscal transparency ratings have better credit ratings, better fiscal discipline, and less corruption than comparable countries with lower fiscal transparency.

Putting accountability to work

Micro-level case studies reinforce understanding of the benefits that accrue when citizens have the chance to hold the public sector accountable:

Public expenditure tracking. In 1995, official Ugandan statistics indicated that a three-fold increase in funding for primary education seemed to have produced no increase in enrollments. Improved tracking revealed that, by under-reporting enrollments, local governments were able to divert grants intended for schools to other purposes (up to 98 percent of the total in 1991). The central government responded by: publishing amounts transferred to the districts in newspapers and radio broadcasts; requiring schools to maintain public notice boards on monthly transfers of funds; and strengthening legal provision for accountability and transparency. By 1999 schools were receiving nearly 100 percent of the grant funds.

Community control of program implementation. The EDUCO school program, set up initially as a short-term expedient after the civil war in El Salvador, gave local communities unprecedented responsibility for managing local primary schools, including power to hire and fire teachers. This empowerment of the communities resulted in such significant improvements in teacher performance (and attendance) and student achievement that the program has been made permanent within El Salvador, and also copied by other Central American countries.

Citizen report cards. In parts of India, paying bribes can be a routine part of obtaining public services. One CSO created a “Citizen Report Card” on public service delivery across different agencies and locations. The cards may be having an impact; a 2003 study indicated that bribery had fallen sharply and satisfaction with public services had risen.

Benchmarking. India also provides examples of the creative use of “benchmarking.” This is an approach which collects comparable data on performance and costs of relatively standardized tasks across different local government jurisdictions: for example, the cost of building one kilometer of a standard design of road or a standardized design of primary school. By making this information accessible, through the press and other channels, effective public pressure is built on jurisdictions that are clearly out of line in their performance.

What is Missing, What is Needed

There is much that developing country governments and legislatures must do to enhance the transparency and accountability of public spending, including: publishing detailed budgets, sharing information on actual financial flows (as in Uganda), strengthening the transparency of public procurement, and improving auditing.

But political leaders and civil servants do not operate in a vacuum, and even the strongest and most public-spirited leadership requires the political reinforcement that comes from broader public involvement in the development of national priorities.

In countries where transparency and accountability are well developed, citizens typically exercise their role in public policy-making not by immersing themselves in raw data, but by drawing – directly and indirectly – on the outputs of “interpreters,” such as think tanks and academics, whose own detailed work in turn gets filtered to the public via intermediaries in the media, politics, and elsewhere.

An obvious example is the Brookings Institution itself, which first published its “Setting National Priorities” series, an independent evaluation of key U.S. national budget choices, some 35 years ago.

By contrast, the interpreters of policy information to the public in low- and middle-income countries are generally too few and too weak. There is a need in most developing countries for stronger domestic non-government groups (possibly including think tanks, university bodies, media, and consumer organizations), to monitor, analyze, and disseminate findings on public spending, and help press governments for greater transparency and accountability.

On the substantive side, serious independent work on public spending will require developing CSOs’ capacity to address at least four areas of concern:

- Aggregate fiscal discipline;

- Allocative efficiency of budget funds;

- Transparent distribution of budget spending; and,

- Efficient service delivery.

In terms of staffing profile, CSOs will need to mobilize several key capabilities:

- Dedicated policy professionals to conduct the necessary underlying analysis;

- Capable, respected interpreters and communicators; and,

- Access to international network resources that can provide benchmarking data and best practice standards.

Some of these are specialized functions, which do not easily develop organically. However, the efforts of pioneering organizations suggest that it is possible to build capacity relatively rapidly with the help of well-targeted interventions.

Building on Existing Efforts

Several existing international efforts seek to help improve budgetary quality and transparency. The incentives established by the EU accession process have, according to independent evaluations, encouraged states in Central and Eastern Europe to develop and implement anti-corruption strategies and improve transparency in the use of public resources. Multilateral agencies, including the IMF and World Bank, undertake periodic analytical work on national budget issues within member countries. Several international organizations actively promote work on general governance issues, including CSOs like Transparency International, though to date the main international CSOs have undertaken only limited work specifically on improving transparency and accountability in public expenditure.

Pioneering efforts by a few actors demonstrate the potential of focused externally-assisted interventions. Two programs are of particular relevance:

- The International Budget Project has worked since 1997 to assist CSOs in new democracies and low- and middle-income countries to conduct analytical and advocacy work on promoting budget transparency and accountability. The project has provided training, diagnostic tools, and small grants (up to $40,000 each) to groups in more than 60 countries.

- The Open Society Institute’s Revenue Watch Initiative has worked since 2002 to improve accountability in natural resource-rich countries by strengthening the capacity of citizens, governments and other interested parties. Active in more than 20 resource-rich countries, Revenue Watch conducts and disseminates research, advocates for transparency and accountability, and supports civil society capacity building, including working with the media, local NGOs, and the public through workshops and small grants.

Despite these groundbreaking programs, clear limitations remain to current efforts on fiscal transparency in developing countries. First, gaps remain in country coverage. Second, coverage within countries needs greater depth, and more budget components need assessment. More fundamentally, analysis by outside agencies like the World Bank and IMF, however technically sophisticated, cannot fully substitute in a political sense for homegrown, domestically “owned” capacity.

How to Get It Done

With possible exceptions, most national governments will likely not attach high priority to financing local institutions inherently geared to holding their own actions up to critical public scrutiny. As such, the strengthening of independent capacity to evaluate public spending will require assistance from sympathetic sources of funding other than domestic national governments. This may include private foundations, multilateral organizations, and/or bilateral government programs.

Support should include grants that fund the preparation and implementation of institutional development plans to address critical CSO functions, including the capacity for research, analysis, communications, advocacy, and networking, as well as essential administrative functions such as personnel and financial management.

Learning-by-doing exercises, which involve commissioning specific analytical work, should also be funded. This approach, which has been followed (in other contexts) by the World Bank Institute, United Nations Development Program and the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research, allows more effective integration of external experts, delivery of technical assistance better-targeted to an organization’s actual needs, and an opportunity to monitor the impact of the intervention.

Additionally, support should be given for a range of networking and knowledge-sharing activities, including: workshops (some cross-country) to share lessons learned and best practices, and collaborate on new strategies; competitive scholarships for individual researchers to do advanced studies; development of publications to disseminate work to a broader audience; a network internship program; “twinning” arrangements that match-up individuals or teams working on similar subjects in different countries, and dissemination of benchmarking data and best practice public sector standards.

Summing up

To improve developing countries’ effectiveness in utilizing scarce public funds, efforts to achieve greater transparency and accountability in budget processes must be strengthened. This brief argues specifically for expanded initiatives to strengthen domestic civil society capacity – independent of governments – to provide substantive analysis of budget choices and the distribution and effectiveness of public spending, and to make the results accessible to the general population both directly and via intermediaries such as the media.

The proposal works from the premise that domestic civic and non-governmental organizations already possess relevant resources, including local knowledge and credibility, that can potentially play a key role in helping to improve the transparency and quality of public spending.

Building on promising pilot programs already underway, the proposal advocates scaling up international efforts to support relevant local actors with training, technical assistance, and facilitated access to the stock of international knowledge on public expenditure review.

Improving the process of setting budgetary priorities, making sure public funds are spent as planned, and raising the effectiveness of publicly financed services, will require sustained efforts by dedicated personnel with local credibility. Successfully managed, such efforts hold the potential to improve current development efforts in a major way, and thus contribute to improved progress in meeting development objectives, including the internationally-agreed Millennium Development Goals.