Executive Summary

In the last year, America has sought to refocus its diplomatic and military attention to East, rather than Middle East. This makes perfect sense. The last decade of wars in the greater Middle East have been draining in terms of both blood and treasure, while the Asia-Pacific region appears to be the new center of future world politics and economy. The region has been described as “the demographic hub of the 21st century global economy, where 1.5 billion Chinese, nearly 600 million Southeast Asians and 1.3 billion inhabitants of the Indian subcontinent move vital resources and exchange goods across the region and globe.”[1]

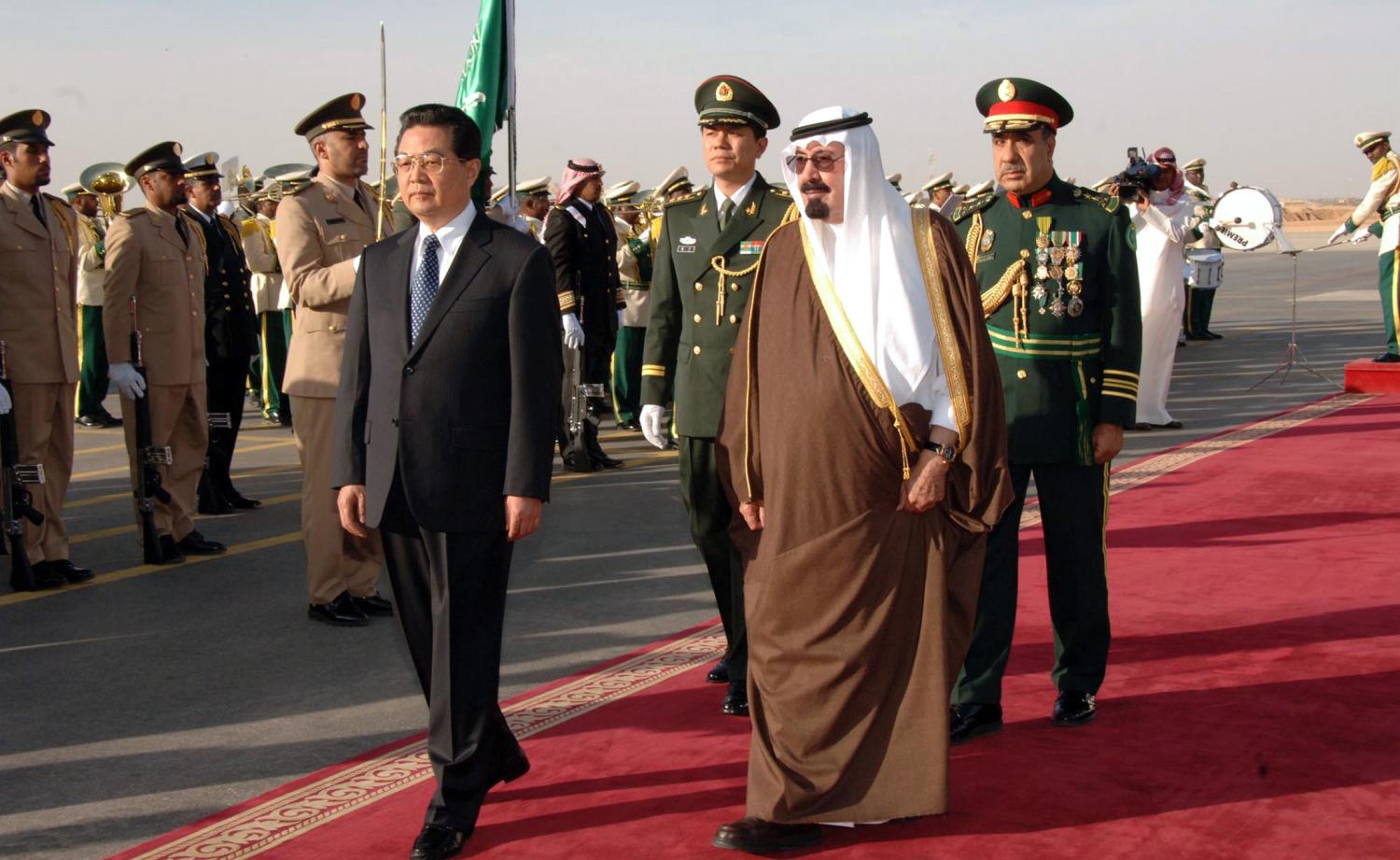

Yet, there is an irony. While the US is looking more towards the Pacific, China’s needs are driving it more towards the Middle East. To fuel and sustain economic growth, China is heavily reliant on Middle Eastern oil. The resource rich and volatile Middle East is a critical center of gravity for the Asia-Pacific and the key for China’s continued economic prosperity.

Therefore, despite the rebalancing of U.S. efforts away from the Middle East to the Asia-Pacific, the Middle East today is fast becoming an arena for another “Great Game,” one that may inevitably pit the U.S. against China in a regional competition for influence and power. China, through its economic ties to the region, has already achieved influence parity with the U.S. Now it could very well leverage this growing influence to gain further concessions and achieve a future positional advantage to counter U.S. regional hegemony and naval supremacy in both the Middle East and within the Asia-Pacific region— all the way from the source of its energy supplies through its long and vulnerable sea lines of communications (SLOCs) and to home ports in China.

The purpose of this paper is to illustrate how China could leverage its use of soft power and regional allies as a strategy within the Middle East of an asymmetric anti-access and area denial (A2/AD) through other means. This novel approach may allow China to “circumvent America’s traditional military strengths,”[2] during a crisis. Thus, the monograph note the limits of any strategic rebalancing that ignores ongoing political and economic dynamics across regions. The U.S. may want to pivot away from the Middle East, but in reality the Middle East remains the focal point for the continued economic prosperity of the Asia-Pacific region, U.S. national interests, and U.S allies’ energy needs in the Middle East. A continued presence in the region will be of critical value to strategic efforts in the Asia-Pacific, serve to assure allies, safeguard the flow of oil and thus promote global economic and political stability.

[1] Kaplan, Robert D. and Cronin, Patrick M. “Cooperation from Strength: U.S. Strategy in the South China Sea.” P.9.

[2] Greenert, Jonathan and Schwartz, Norton. “Air-Sea Battle Doctrine: A Discussion with the Chief of Staff of the Air Force and Chief of Naval Operations.” (Brookings Institution, 16 May 2012). P.9. Available from: https://www.brookings.edu/~/media/events/2012/5/16%20air%20sea%20battle/20120516_air_sea_doctrine_corrected_transcript.pdf Internet accessed 12 June 2012.