The markets don’t appear to believe the Fed.

There is a significant difference between the interest-rate path that Federal Reserve officials sketched in December, the last time they made public projections, and the rates implied by trading in futures markets. The markets see a smaller, more gradual increase in interest rates than the now-famous dots that show where Fed officials expect interest rates to go.

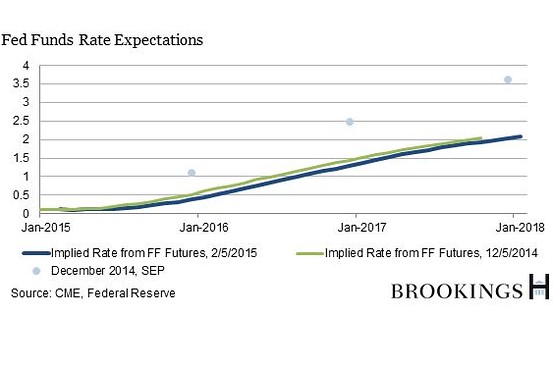

The chart above illustrates this, using the median forecast for Fed funds from the Federal Reserve’s December “Summary of Economic Projections” alongside the rate implied by Fed funds futures for the same month (light green) and for this week (dark green.) By January 2017, for instance, the markets project that Fed funds, which are now around zero, will be up to 1.375%. In December, the median Fed official saw 2.5%.

What explains this persistent divergence? I’ve heard three reasons, and there’s probably some truth to all of them.

First, financial markets are not interested in the median Fed official; they’re interested in Chairwoman Janet Yellen, and they assume her dot is lower than the median. That is, they expect her to want to move much more cautiously to raise interest rates than the median Fed policymaker. After all, she has suggested that significant slack remains in the labor market even though the headline unemployment rate–at 5.7%–has fallen close to the Fed’s estimates of a level that would be long-term sustaintable. And Ms. Yellen has urged Fed watchers to pay more attention to the Federal Open Market Committee’s statements than to the accompanying interest rate projections.

Second, the markets think Fed officials and staff economists are overly optimistic about the U.S. economy, as they have been in the past, particularly in light of the troubled condition of nearly every major economy outside the U.S. (with the exception of Britain). Markets reason that the Fed will have to move more slowly to raise interest rates because the U.S. economy–and job market–won’t be as strong as the Fed expects.

Third, there’s the inflation issue. Many do not believe that the Fed will raise rates until underlying inflation is a lot closer to its 2% target. The Fed has said that it needs more confidence that inflation is headed up to the target before any movement on interest rates will be seen. The Fed’s favorite inflation measure, the personal consumption expenditures price index, climbed only 0.75% in the 12 months ending in December; excluding food and sinking energy prices, it was up 1.33%–and moving in the wrong direction.

Ms. Yellen and her colleagues have noticed the markets’ skepticism, and they have to decide whether to respond. We’ll get a better sense of the Fed’s evolving thinking on Feb. 18, when minutes of its Jan. 27-28 meeting are released, and from Ms. Yellen’s testimony before the Senate Banking Committee on Feb. 24. But we won’t get the next FOMC statement and a new set of dots until mid-March.

Commentary

Op-edWhat’s Behind the Federal Reserve’s Credibility Gap on Interest Rates?

February 6, 2015