Progressives, these days, are a gloomy bunch, and it’s not just because of the outcomes of last week’s election. As they see it, there’s much to be gloomy about: Poverty levels are stuck, they say, with little improvements made in recent decades. What’s more, according to the standard progressive line, income inequality is soaring, and back to levels last seen in the roaring ’20s. And, to top it all off, middle class incomes are flat, or even falling.

But here’s the thing: Each of these claims is a significant overstatement. In fact: Progressives have every reason to be celebrating right now. Why? Because by and large, things aren’t so bad as progressives claim, and the reason things aren’t so bad is because progressive policies are working. Medicare and Medicaid, Earned Income Tax Credits, tax cuts favoring the working poor, expansion of health coverage, and so on—all of these policies are making Americans better off than they would otherwise be.

Poverty: Down

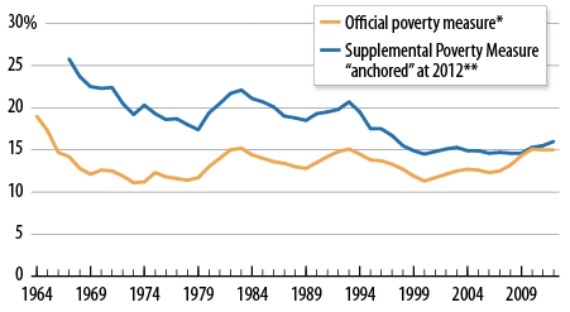

The official poverty measure is next to useless, given that it was set in the 1960s, and fails to take account of real incomes. If we use a more robust measure, one that includes the value of government benefits and transfers and treats income taxes (and tax credits) in a plausible way, poverty has actually fallen quite sharply in recent decades:

Percent of People Living in Poverty

* Counts cash income only and uses the official poverty line

** Counts cash income plus non-cash benefits, reflects the net impact of the tax system, subtracts certain expenses from income, and uses a poverty line based on today’s cost of certain necessities adjusted back for inflation. (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities)

That decline is the consequence of successive government interventions to improve living standards for lower-income Americans. Today, government transfers and credits keep around 40 million Americans out of poverty. Seven out of eight of these people would be poor today if the safety net were only as effective as it was in 1964, according to calculations by Arloc Sherman at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Social Security alone slashes 8.6 percentage points off the poverty rate, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

Poverty? Government cut that.

Inequality: Mostly in Check

One of the staple progressive mantras is that income inequality is soaring, with the minority at the top vacuuming up most of the national income. But the picture is much more complex, and more positive, than that. Critically, the most dramatic figures for inequality are generated by looking at “market income”—i.e. before any taxes and transfers.

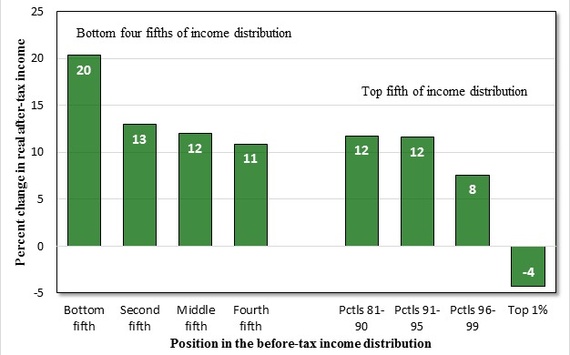

Between 2000 and 2010, the biggest gains in real after-tax income were actually at the bottom of the ladder:

Change in After-Tax Income by Household Position in the Income Distribution, 2000-2010

Each household’s position in the income distribution is determined by its rank in the before-tax income distribution. (Data: CBO Chart: Gary Burtless/Brookings)

The maintenance of incomes at the bottom of distribution is the result of strenuous government efforts to mitigate the effects of inequality, especially by cutting taxes and/or providing tax credits to lower-income Americans. Without this government action, inequality almost certainly would have risen quite sharply in the bottom 90 percent.

Having said this, there was a clear a rise in overall inequality in the 1980s, and there has been a pulling-away of the very richest in the top 5 percent or even 1 percent of the distribution in more recent years (see graph below). There may be reasons to worry about the income growth at the very top, particularly in relation to political power. It may be that the redistributive capacity of the government is reaching its political or fiscal limits. And there is good reason to worry about the growth of wealth, as opposed to income, inequality. But in terms of income, the real story of the last few decades is that rising market inequality has by and large not translated into final inequality, largely because of government action.

Inequality? Government curbed that.

Middle Class Income: Supported

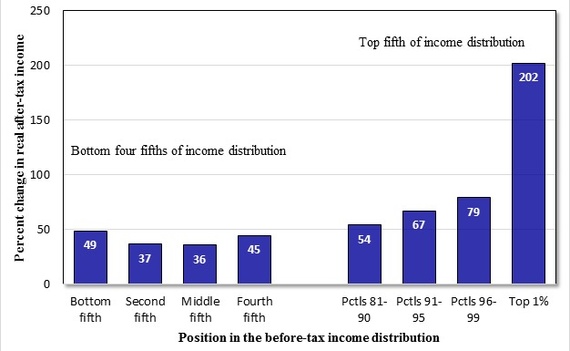

The state of the middle class is also a point of distress for many progressives, and there are causes for concern. But the panicked tone of some political rhetoric is misplaced. Certainly the golden years of income growth enjoyed after World War II are behind us. But it is simply false to imagine that the American middle class is sinking. People at the top of the income distribution have done much better than most. But it is also clear that real incomes have risen across the board in the last three decades:

Change in After-Tax Income by Household Position in the Income Distribution, 1979-2010

Each household’s position in the income distribution is determined by its rank in the before-tax income distribution. (Data: CBO Chart: Gary Burtless/Brookings)

This graph, produced by my Brookings colleague Gary Burtless using CBO data, comes as a surprise to many. The first point to make is that the top fifth of households have enjoyed much bigger gains. As discussed above, the 1980s were good decade for them, and in more recent years those at the very top have also done very well.

But the picture for the majority is not particularly gloomy either. Why? Well, one important point is that the condition of middle-income households should not be conflated with the state of middle-income men, since most of those households also contain women, who have been doing much better, seeing sharp rises in employment, relative educational attainment, and wages over the past three decades. Of course, a family may be worse off in some important ways if both parents need to work to get the same income, and so the “saving” of household income by working women is not always seen as a success, but if that is the problem, we should be more explicit about it.

Again, a good deal is owed to state action. First, by using legislation to combat workplace sexism, the government helped pave the way for the transformation in women’s incomes and jobs. Second, tax credits have played a significant role in lifting incomes for working families. Third, the value of in-kind benefits from employers and the government—above all, on health insurance—has risen significantly for middle-income Americans, particularly since the passage of the Affordable Care Act. For households in the middle fifth of the distribution, these benefits accounted for 17 percent after-tax income in 2010, up from 6 percent in 1980, according to Burtless.

Middle-class incomes? Government boosted those too.

* * *

Caveats are needed here. The war on poverty has been much more successful than either side cares to admit, but it is far from over. Inequality is still be too high, even if it hasn’t widened for most of the population. Living standards in the American middle-class life are not ‘stagnant’—but the de-coupling of median earnings and growth is a real worry. Market incomes and inequality matter.

The truth is this: Most Things Are Getting Better for Most People, Even If a Bit More Slowly Than in the Past, and There are Plenty of Things that Can, and Should, Be Better Still. (Not a great bumper sticker, I admit.)

So why are progressives such Eeyores? Here’s one theory: In order to justify government action, they overdramatize the scale of the problem at hand. Unless you can convince voters there is a real problem, what hope is there of gaining support for a solution? Progressives want to redistribute further, so they must declaim the shocking, soaring levels of inequality. To win the battle for a higher minimum wage, they lament the collapse of middle-class incomes. (And note that four states did vote to raise their minimum wage, while simultaneously electing Republicans.) To gain support for anti-poverty measures, they highlight an unchanging record on American poverty.

For progressives, doom and gloom will be a self-defeating political strategy, since it adds steadily to the sense that government doesn’t work. This will be especially true in 2016 after occupying the White House for two terms. The subtext of downbeat progressive rhetoric is, by implication: “Yes, we have already done all these things (the Great Society, tax credits, welfare reform, food stamps), but honestly, nothing has really worked, look how terrible things are becoming.”

What they should be saying instead is: “Look at all these government initiatives that have really worked to reduce poverty, improve workplaces, lessen inequality, weaken racism, boost women’s chances, and improve wellbeing. So let’s do more of it! What’s the next problem that we can help to solve?”

Commentary

Op-edProgressives Lost the Election, but Their Ideas Are Winning

November 10, 2014