Content from the Brookings Institution India Center is now archived. After seven years of an impactful partnership, as of September 11, 2020, Brookings India is now the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, an independent public policy institution based in India.

This article first appeared in the Mint. The views are of the author(s).

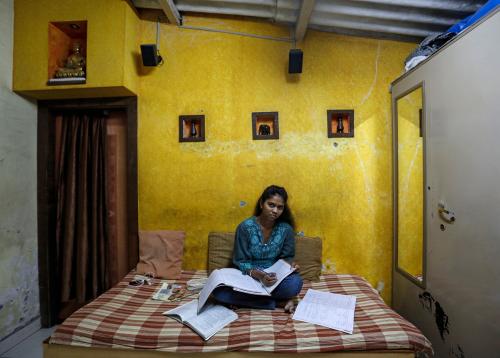

It is that time of the year when India struggles to meet the educational expectations of its youth. An increasing number of school graduates are enrolling in college but the shortage of quality institutions has led to unreasonable entrance requirements. Despite recent visa restrictions, the US remains a favoured destination for resourceful Indians seeking higher education opportunities. An estimated 100,000 Indian students advance innovation and research in US universities, and have the potential to make significant contributions in such sectors as science, business, health and agriculture when they return to India. It therefore makes sense for both India and the US to strengthen ties in higher education. There are four critical areas for cooperation.

Financing: This is a major bottleneck in the Indian higher education system. With pressures to cut fiscal deficits and tight government budgets, there is an extreme shortage of resources for expanded access. To overcome this bottleneck, the government has allowed foreign universities to open campuses in India. However, regulatory constraints and a cumbersome bureaucracy remain serious impediments.

Teaching quality: The quality of a higher education degree is only as good as its curriculum and the quality of the teachers. Universities are unable to compete with rising private sector salaries and find it difficult to recruit and retain top-quality teachers.

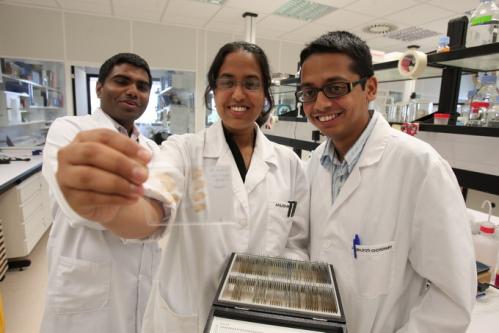

Research: Good independent research, the hallmark of any global university, actively feeds into pedagogy through cutting-edge curricula, promotes business development in the corporate sector, and can be an anchor for government policymaking. Except for a handful of stand-alone research institutes, India lacks the culture of independent academic research and can learn from the experience of the US higher education system.

Governance: For higher education institutions to compete globally, India must develop a robust university governance structure. India could learn from the regulatory framework and accreditation system of the US higher education sector that make it flexible and innovative.

The US Agency for International Development (USAID) is tasked with providing a range of high-level analytical, diagnostic and organizational development services to support the efforts of the Union ministry of human resource development (MHRD) in setting up Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs). USAID is also going to boost the In-STEP project (India Support for Teacher Education Program) through three-month customized training programmes for over 100 Indian teacher-educators at the Arizona State University. This would enable the teacher-educators to offer high-quality training to Indian teachers back home, thereby raising the overall teaching quality.

Starting 2012, both countries have also pledged $5 million to the 21st Century Knowledge Initiative, to support research and teaching collaboration in the fields of energy, climate change and public health. The Fulbright-Nehru programme supports more than 300 scholars between the two countries. The US government has relaunched the “Passport to India” initiative, in partnership with the Ohio State University, whose main objective is to work with the private sector to increase internship opportunities, service learning and study abroad opportunities in India. The India-US Higher Education Dialogue creates opportunities for student mobility and faculty collaboration across the two countries through initiatives such as the Global Initiative of Academic Networks (Gian) programme, where the MHRD creates a channel for US professors in science, technology and engineering to teach in Indian academic and research institutions on short-term exchanges. Indian institutions will gain tremendously from such visits, and such appointments should be facilitated and strongly advertised.

Given the gap between the quality of higher education in Indian institutions and the demands of the job market, skilling is a top priority for the current government. Employability is a key concern and several efforts are being made to encourage new certification programmes, knowledge sharing and public-private partnerships between the two countries. For example, there is an agreement between the All India Council of Technical Education (AICTE) and the American Association of Community Colleges (AACC) for curriculum development and training of the future workforce.

Beyond government initiatives, Indian universities also have to develop an incentive structure that would welcome such collaborations with US universities. How can such collaborations be made independently sustainable? Do Indian universities have the flexibility to employ high-quality foreign faculty? Would Indian universities accept course credits for students who spent semesters in US-regulated universities?

Most of these ideas highlighted for US-India collaboration will remain token measures until the Indian higher education system undergoes a tectonic shift in its governance structure and regulatory framework. The announcement to reform the University Grants Commission (UGC) is a very welcome move, and if done right, it will improve access to quality higher education for Indian students and raise the research and teaching capacity of India’s faculty pool.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edAdvancing cooperation in higher education

June 22, 2017