This piece originally appeared in UCSD’s China Focus blog. The interview was conducted by Jack Zhang (张嘉琨), a PhD student in the Department of Political Science at UCSD.

You have an upcoming book on Chinese Politics in the Xi Jinping Era: Reassessing Collective Leadership. Could you give our readers a synopsis of your main arguments?

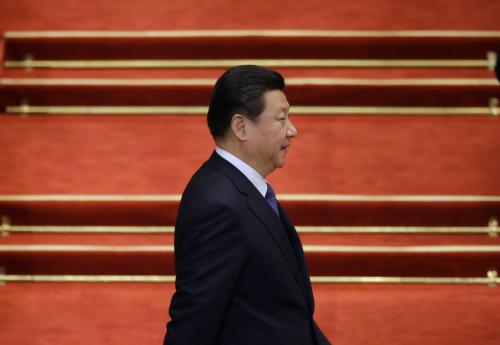

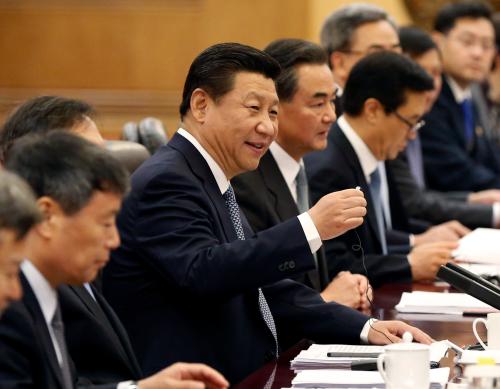

Views in the United States about Xi Jinping and Chinese politics fall to two extremes. On one extreme is the belief that Xi Jinping is a “strong man” who has completely replaced the collective leadership and is monopolizing power. He is an ambitious leader who has helped realize China’s military modernization, which will enable China to dislodge the United States from the Asia Pacific and cement its own regional hegemony. Under this scenario, the U.S. policy approach is to contain China before it’s too late.

At the other extreme is the view that Xi Jinping is weak: his anti-corruption campaign and military reforms have alienated many people and created numerous enemies. This view perceives Xi’s tenuous grip on power and deduces that the Chinese Communist Party itself is imperiled. If forces seek to push aside Xi Jinping, the thinking goes, the days of Communist Party rule could be numbered. Ironically, the view of “weak Xi” reaches the same policy recommendation as the view of “strong Xi”: the United States should contain China because there is no political cost to doing so.

Both of these views are highly problematic and, as I argue in my book, China’s reality is somewhere in the middle. If we’re guided—or misguided, I should say—by these two extreme views, we will lose the opportunity to work with the Chinese leadership, which will hurt U.S. interests. Xi’s position and background afford him significant influence, but he is also constrained by the system in which he operates. As a starting point, we should give credit to Xi Jinping and his leadership team for their accomplishments over the past 3-4 years. In my view, Xi has concentrated his attention in a lot of the right areas: launching the anti-corruption campaign and reforming the military were absolutely priorities. Carrying out market reforms, which is what the third plenum focused on, is also prudent, although many items on the agenda have not yet fully materialized. But if you are a leader faced with these three massive tasks—military reform, anti-corruption, and economic reform—what’s the optimal sequence? What should take precedence? I think the sequence he’s pursued has been effective. Emphasizing anti-corruption and military reform has allowed him to consolidate power, which will help prevent another possible wave of corruption as market reforms are carried out.

With respect to constraints on Xi, I think China’s collective leadership model, which emphasizes deal making and compromise over zero-sum elite competition, is alive and well. It is more enduring and sustainable than most people believe. My book contains 80-plus tables and charts detailing the fine-tuned balance of power within the Politburo and the Central Committee. Regional interests play a key role in this balance of power, and Xi Jinping derives much of his own influence from the fact that he unites two geographic power bases. His career advanced in coastal China—Fujian, Zhejiang, and Shanghai—but he also maintains close ties to Shaanxi, where his father is from and where Xi spent time as a sent-down youth. So that gives him support from both inland and coastal regions—something few leaders are able to muster. Even so, there are still the northeastern, central, and southern parts of China, where coalitions have formed to compete with and constrain Xi’s power. So the Chinese system of checks and balances still works.

If you consider the Bo Xilai case and reflect on events of the past three years, you see that the greatest obstacle to successful governance in Chinese politics is corruption and abuse of power. But the system has proven extremely resilient: thanks to internal reforms and existing mechanisms like coalition-building and the factional balance of power, corrupt leaders have been ousted to ensure the overall system’s survival. Just as these mechanisms can function to preserve the power of the Communist Party, they can also operate to constrain individual leaders. Xi Jinping’s legacy will largely depend on whether he promotes or opposes the long-term trend of political institutionalization. This cannot be judged based on the past 3-4 years, but rather will depend on Xi’s entire 10-year term. I hope the 19th Party Congress will open the door to further advances in political institutionalization and “intra-party democracy,” as the Chinese call it, and also for institution-building rather than over-reliance on individual power. This is a main theme of my book.

We ran an interview with Jerome Cohen about the rule of law, in which he talked about the tough time lawyers are having under Xi Jinping. But you have been very bullish towards the development of the legal profession in China. What are the prospects for the rule of law in China given the increased repression under Xi Jinping?

I greatly admire Jerome Cohen, who is one of the most respected thinkers in the China field and a dear personal friend. But I admit that I am far more optimistic than him. I have edited several volumes for the John L. Thornton Center Chinese Thinkers Series, featuring work by scholars such as Yu Keping (俞可平), He Weifang (贺卫方), He Huaihong (何怀宏), and Hu Angang (胡鞍钢). Let’s first talk about Yu Keping. He was one of the first Chinese scholars to elucidate the difference between rule of law (法治) and rule by law (法制), which have the same Chinese pronunciation but are different characters and distinct concepts. “Rule by law” means that the party is above the law, while “rule of law” means that the party should be held accountable under the constitution. Yu Keping favors the establishment of rule of law. Of course, that battle has not been resolved in China yet. Some days leaders say there should be rule of law but other days they say the party should be above the constitution. This ambiguity at the official level summarizes the current status of legal development in China.

We also published a book by another scholar, He Weifang, titled In the Name of Justice: Striving for the Rule of Law in China《因 正义之名:在中国推进法治》. The project was initiated in 2009-2010, but He Weifang was sent to Xinjiang for two years so we delayed it. We restarted the project when He returned to Beijing in 2011. In the manuscript, He basically challenged three people: Wang Lijun (王立军), Bo Xilai (薄熙来), and Zhou Yongkang (周永康). Again, this was in 2011, before Wang Lijun sought refuge in the U.S. consulate in Chengdu. By the time the book was published in 2012, Wang Lijun and Bo Xilai were already in jail but Zhou Yongkang, who has since been purged, was still in power. He Weifang remains a law professor at Peking University. This case shows that a book by a law professor can openly challenge the leadership and their abuses of power. He Weifang’s story suggests that we should not be so pessimistic about Chinese legal development.

Xi Jinping has also talked about the rule of law. The fourth plenum was dedicated to discussing this topic, the first such plenum in CCP history. But public discourse has centered on issues like media control, the harassment of intellectuals, and the arrests of civil rights lawyers. Those who emphasize these issues consider Xi Jinping to be against legal development, but that does not capture the entire story. The fight for justice and constitutionalism is not an easy journey in any country. And China is no exception. But based on the work of He Weifang and Yu Keping, I do see cause for hope. And the fact that an increasing number of Chinese leaders have received law degrees—for example, Premier Li Keqiang, President of the Supreme People’s Court Zhou Qiang—is also significant.

I want to clarify, do you think rule of law in China will come through elite competition, as it did in the UK, within the party or from bottom up demand from outside of the party? In other words, could political institutionalization be happening among elites within the party but another set of rules apply to how the government deals with the people?

It’s happening both ways. Chinese elites are increasingly diverse—in terms of family backgrounds, political associations, occupations, world views, and regional connections. Not to mention the factional diversity between the so-called tuanpai (Chinese Communist Youth League) and princelings (leaders who come from prominent family backgrounds). This multi-layered diversity is an important component of China’s system of checks and balances. On the other hand, we should look at elite incentives and broader changes in society when thinking about a country’s transition to democracy and the rule of law. In China, important developments include the rise of the middle class, the commercialization of the media, and, as we discussed, the emergence of the legal profession.

To your earlier point about increased repression under Xi Jinping, human rights lawyers outside of the system are just as important to the debate as scholars like Yu Keping and He Weifang, who are pushing for change inside the system. Of course, we have seen harassment. While this is terrible, it should not come as a surprise. As long as legal development and constitutionalism are emphasized, the door will be open to legal contention. If you challenge the fundamental interests of interest groups, you will see some backlash.

In 2014, we hosted a debate by Victor Shih and Barry Naughton on the motion: “The Chinese economy will collapse in five years.” The audience was convinced by Victor’s perspective that the Chinese economy will collapse. So our final question for you is, what are the prospects for Chinese economic reforms succeeding before 2020? Do you agree with the debate outcome?

China is currently experiencing an economic slowdown. Chinese leaders acknowledge that this time the slowdown is very serious. It is highly unlikely that China will have a “V-shaped” economic recovery like in 2008-2009 or a “U-shaped” recovery like in the late 1990s. Instead, this recovery will likely be “L-shaped,” indicating a prolonged period of slowed economic growth. Not only do critics make this argument, but also some leaders. Part of the slowdown is intentional because of environmental concerns; China doesn’t want to have more of the so-called “single-minded GDP growth.” Rather, leaders want more of what Xi Jinping has called “quality growth.” Nevertheless, China’s economic slowdown is also occurring amid a global economic slowdown, so there’s an increased risk of an economic crisis. This all speaks to the seriousness of the economic situation.

On the other hand, several basic attributes of the Chinese economy work in its favor. First, China already has a sizable middle class, which is a driving force for tourism and consumption. Domestic consumption is already picking up. Second, China has built world-class infrastructure, which is important for facilitating consumption and moving up the value chain. Third, the Chinese spirit of entrepreneurship that fueled the Chinese economic miracle remains healthy. Put simply, Chinese people work hard and want to make more money. And China, perhaps more than any other country, embraces economic globalization. Even though there is a strong sense of nationalism and a great deal of criticism about American containment, anti-globalization forces in China have not caught on as they have in the United States, the United Kingdom, and elsewhere. So all of these foundational elements leave China in relatively good shape.

Debt and bad loans in state-owned enterprises, environmental degradation, and a dearth of natural resources are all important and constraining issues. But China has a lot of capital, and the government has strong incentives to deal with these problems. The collapse scenario is always a risk, but I am not so pessimistic. In my view, it has perhaps only a one-percent chance of occurring, even though public discourse would lead you to believe that the likelihood is closer to 90 percent. From a broad historical perspective, what we see in China is its unprecedentedly rapid and persistent rise, not its decline. But that rise is not—and has never been—linear, so it’s understandable that fluctuations still occur. Despite the problems of the last several years, China has maintained a 6.5- or 7-percent GDP growth rate, its consumption contributes to the global economy, and its economy is already the second largest—soon to be the largest—in the world. As I argue in my new book, it is important not to lose sight of the big picture.

Commentary

Chinese politics, economy, and rule of law

September 20, 2016