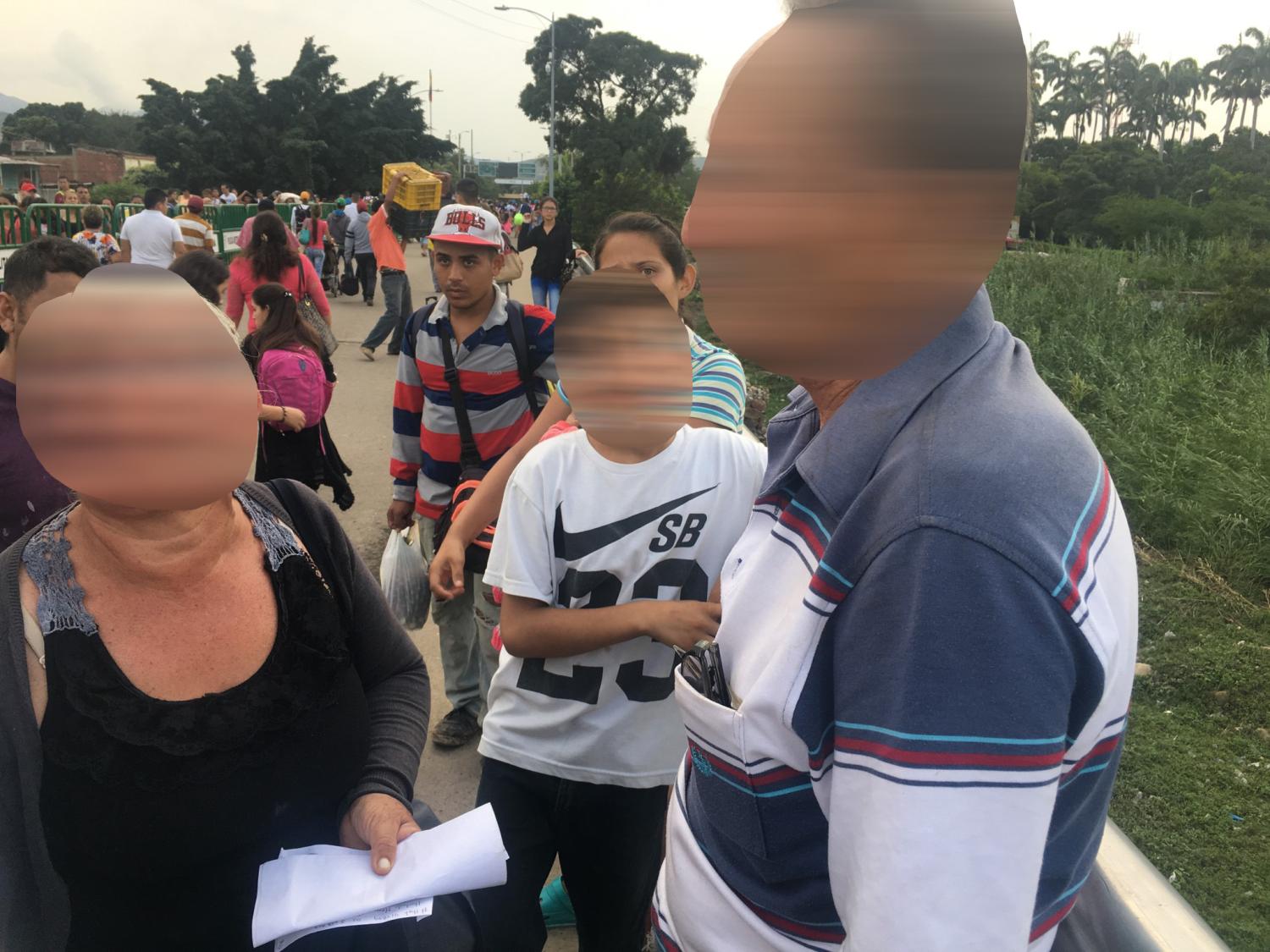

From April 7-9, I visited Cucuta, a Colombian city bordering San Antonio del Tachira in Venezuela, to understand the dimensions of the Venezuelan refugee crisis. That border is one of the most active crossings between the two countries, and over the past year it has become increasingly transited by Venezuelans. Official figures estimate that about 35,000 Venezuelans cross the border on a daily basis, but unofficial estimates from observers on the ground estimate that number to be much higher. It is also estimated that somewhere between 3,000 and 5,000 people crossing stay in Colombia or travel to another country in the region. The rest are crossing for a few hours or a few days to work and/or get food and medicines not readily available in Venezuela. Below are some pictures and stories of places I visited and people I met during my visit.

Commentary

Venezuela’s refugee crisis: Views from the border

April 23, 2018