Higher income tax receipts in adulthood offset half of childhood Medicaid expenditures

Combining data on Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program expansions in the 1980s and 1990s with income tax return data, David Brown and Ithai Lurie of the Treasury and Amanda Kowalski of Yale University find that children who experienced a longer period of Medicare eligibility paid more in taxes by age 28 as a result of higher earnings. Extrapolating into the future, the authors suggest that by the time the subjects reach age 60, higher income tax receipts could offset 56 cents of every additional $1 spent on Medicaid in childhood.

Financial aid increases college enrollment and persistence – especially for at-risk students

Using data on randomly assigned financial aid offers in the Nebraska public college and university system, Joshua Angrist, David Autor, and Sally Hudson of MIT and Amanda Pallais of Harvard University find that financial aid offers significantly increased the fraction of students choosing to attend four-year colleges and increased overall sophomore enrollment by 7.2 percentage points. Nonwhite students and students with ACT scores below the state median experienced the largest and most persistent gains in enrollment.

S&P projects significant returns to infrastructure investment

Standard & Poor’s Economic Research division estimates that a $160 billion increase in U.S. infrastructure spending in 2015 would increase economic output by $270 billion and create roughly 730,000 jobs over the next 3 years. They note that the economic returns from infrastructure investment are currently high throughout most of the G20, particularly for countries such as China, India, and Brazil, each of which have expected multipliers of 2.0 or greater.

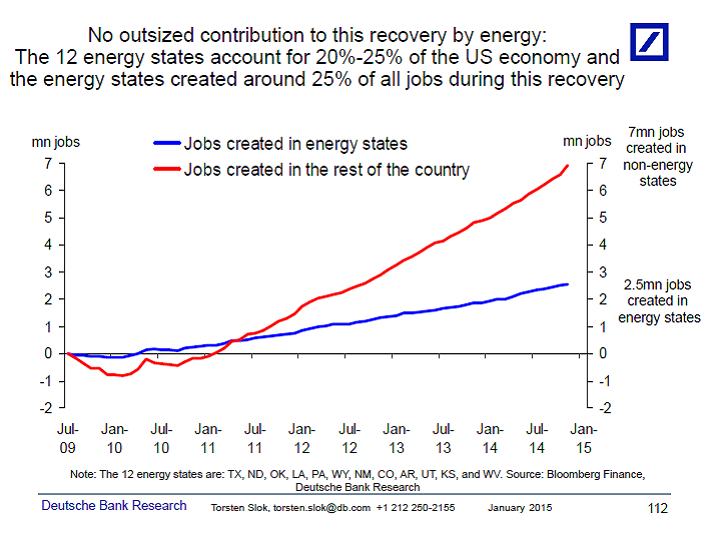

Chart of the week: Job creation

Speech of the week: Kocherlakota: Raising the fed funds rate in 2015 would be an obstacle to the ongoing recovery

“My own current assessment is that it will take a few years for inflation to return to 2 percent from its current low level. As I noted earlier, monetary policy affects prices with about a two-year lag. Raising the target range for the fed funds rate in 2015 would only further retard the pace of the slow recovery in inflation. It would also increase the risk of a loss of credibility, in the sense that the public could increasingly perceive the FOMC as aiming at a lower inflation target. Hence, given my current outlook for inflation, I anticipate that, under a goal-oriented approach, the FOMC would not raise the fed funds rate target this year.”

—Narayana Kocherlakota, President, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis

Commentary

Hutchins Roundup: Medicaid, Gains From Financial Aid, and More

January 15, 2015