Dramatic storms, wildfires, floods, and similar events draw the most public attention as examples of how climate change threatens human lives and homes. But more subtle, persistent changes in the environment, such as sea level rise and increasingly hot summers, are also creating health and safety hazards across the U.S.

One example is the Tidewater region of Virginia, where sea level rise is causing frequent failures of home septic systems. In Virginia alone, over 1 million homes rely on individual septic tanks rather than public sewer systems for residential sewage treatment. And when septic systems fail, the results are catastrophic—polluting drinking water and threatening human health. The burden of repairing septic tanks and mitigating the impact on neighbors falls mostly on homeowners and local governments—a particularly tough challenge for smaller, less affluent rural communities.

Older home septic systems weren’t designed to withstand today’s rising water levels

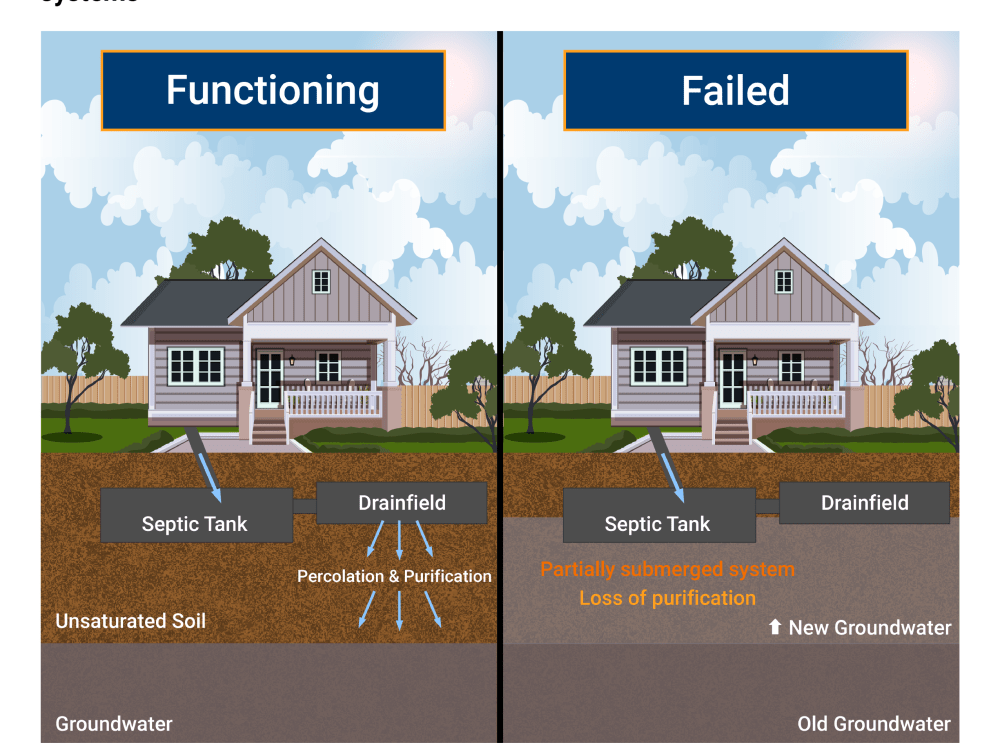

A septic tank is a buried, watertight container that is used to dispose of residential sewage. It was widely used before the adoption of the more modern sewer system, but many are still in use today. Septic tanks hold residential wastewater and then allow sewage to slowly seep into an unsaturated drain field, where the water can percolate into the soil. When water tables rise due to heavy, prolonged rains, coastal storms, or sea level rise, septic tanks are unable to function properly, causing sewage to seep into drinking water or onto the surface, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Virginia has one of the highest rates of sea level rise, at 5.1 mm per year, compared with global rates around 3.2 mm per year.

Virginia has one of the highest rates of sea level rise, at 5.1 mm per year, compared with global rates around 3.2 mm per year.

A 2021 analysis of the Tidewater region illustrated that there are an increasing number of “hot spots” where septic failures occur annually. Areas with a high density of failures are frequently located in places that impact water supply quality, such as at the top of streams or creeks. Crucially, these rising failures can pollute drinking water from wells and may seep into nearby rivers and streams—affecting not just the homeowner whose septic system fails, but the surrounding community as well.

Data gaps, fiscal challenges, and fragmented governance impede climate planning

Assessing possible solutions to the septic problem—including estimating the costs of various interventions—requires local policymakers (and potentially state and federal policymakers as well) to have reliable data on some basic questions. How many homes that rely on septic systems are in high-risk areas? How many are in “safe” areas that could become high risk in the near future? How many homeowners have sufficient savings or access to credit to pay for repairs themselves, and how many will require subsidies?

Unfortunately, up-to-date data on the use of home septic systems with sufficient geographic detail to plan policy solutions does not exist. Many communities have no official measures of exactly how many homes use septic tanks for wastewater treatment. The Census Bureau’s American Community Survey—the most widely used data source on housing and demographic characteristics—has recently approved a “Septic or Sewer” question that will finish testing in 2023.

In 2019, Virginia’s state government created an interagency agreement to establish a wastewater working group and noted a need to “improve data reporting to help identify pockets of needs.” The agreement highlights how multiple agencies may need to engage to address the problem—cutting across public health, environmental quality, public works, and community development.

Nationally, older homes are more likely to have septic systems, with only 15% of newly built homes on septic. Unlike sewer systems, which are typically owned and maintained by public agencies or regulated utilities, septic systems are owned and maintained by individual property owners. Existing data is not well structured to identify which homes—and homeowners—with septic systems are both in high-risk locations and face tight financial constraints.

Communities that rely on septic systems run the gamut from high-income, high-priced suburbs and exurbs to low-income rural areas. Smaller communities face especially limited financial resources and staff, both in public agencies and private contractors who typically install and service septic systems. In Virginia’s Tidewater region, the median rural county has just under 12,000 residents—less than half the size of most cities and counties across the state.

Expecting thousands of local governments across the country to simultaneously develop solutions to the same problem is both ineffective and inefficient. Solutions to problems created by climate change will require extensive financial resources, monitoring, data collection, and technical expertise—not to mention coordination across multiple government agencies.

More coordination and funding from state and federal agencies can help local governments address climate resilience

Septic tank failure due to sea level rise is only one example of how climate change harms public health in ways that local governments alone cannot address. State and federal support—especially for small communities with limited financial and staff capacity—is essential to help local governments assess options and implement solutions. Researchers and policymakers at all levels of government should collaborate to answer several key questions:

- Could some homes with septic tanks be connected to existing public sewer systems? What are the physical obstacles to doing this?

- For communities that face the highest, most persistent risk from sea level rise, is it necessary to relocate people and/or homes to safer areas?

- Are there technical innovations (e.g., better designed septic systems) that could be implemented?

- What are the estimated costs of different options? How would these costs be shared among affected property owners, insurance companies, and government agencies?

- Which options face the highest political hurdles? What are the equity implications—would subsidies to individual property owners be contingent on financial need?

Without major policy action, the consequences and risks of septic tank failure will only increase as sea levels and water tables continue to rise. Human health will suffer as a result of sewage and resulting pollution, so policymakers must work to come up with big-picture solutions.

Commentary

Sea level rise from climate change is threatening home septic systems and public health

June 29, 2022