Governors and other state leaders who are working to help the residents of their states cope with rapid economic change recently got a better look at the challenges they face. New research by our Brookings colleagues Mark Muro, Rob Maxim, and Jacob Whiton suggested that while artificial intelligence isn’t likely to eliminate millions of jobs overnight, as many as 25 percent of American workers (36 million people) face “high” exposure to task disruption in the coming decades. That exposure is more concentrated in certain states, especially in the Heartland. More worryingly, companies are accelerating their efforts to automate in order to stay competitive.

The good news is that governors have substantial power to do something about it, especially if they can work in partnership with legislative leaders and a broad set of economic actors in their states. Drawing on the ideas recommended by our colleagues, we lay out a playbook of policies that every governor can champion to help the residents in their state adapt and thrive in the face of automation.

First, it’s worth taking a closer look at this map our colleagues produced, which shows the risk automation poses on a state-by-state basis.

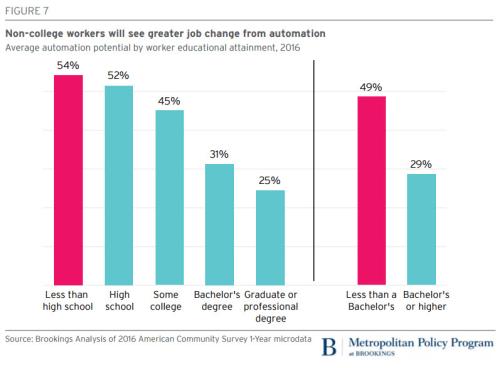

This map suggests that states in the Midwest, Great Plains, and South are most exposed to automation, while ones in the Northeast, West Coast, and Southwest face comparatively less risk. As Muro, Maxim, and Whiton write, these differences can largely be traced to state variations in educational attainment (less educated workforces face greater risks), industrial composition (e.g., manufacturing, agriculture, retail, and food services sectors are more susceptible to automation), and community types (as smaller cities and towns are more likely to face disruption).

States in the Midwest, Great Plains, and South are most exposed to automation, while ones in the Northeast, West Coast, and Southwest face comparatively less risk.

But what’s also notable is that automation poses a significant challenge to all states: Between 40 and 50 percent of all tasks in every state could be automated using today’s technologies, according to our colleagues’ calculations. And the people who are most at risk tend to be younger, less educated, and black or Hispanic (in other words, the groups upon whom America’s future prosperity relies).

So what can governors do to prepare their residents to succeed in an age of automation? We organize our colleagues’ state-relevant recommendations into three broad categories.

Promote a constant learning mindset

Artificial intelligence and other new technologies will require people to adopt new approaches to work. Accordingly, governors should be pulling every lever to ensure that their systems and investments help workers gain needed skills and relevant credentials.

- Promote competency-based learning that allow learners to obtain certifications and credentials for skills they have already mastered and accelerated learning models like tech “boot camps” through which students obtain technical credentials in a short period of time.

- Promote skills-based hiring that encourages employers to hire based on the specific skills needed for the job rather than a non-specific and often inflated requirement like a four-year degree.

- Provide state training tax credits to encourage more employer-sponsored training for specific jobs.

- Strengthen the education pipeline by investing in pre-K and ensuring that the K-12 curriculum requires students to master widely needed skills like computer science, coding, and statistics, and does so in a digital format.

Facilitate smoother adjustment

Millions of workers will see their jobs change or be eliminated in the years ahead, and many will face difficult paths to reemployment. Accordingly, governors should build support systems that help workers adjust to changing conditions and make the transitions between jobs less disruptive.

- Help struggling workers by expanding the state Earned Income Tax Credit to include childless workers, raising income eligibility thresholds, paying credits in regular intervals rather than in an annual lump sum, and making credits fully refundable. Additionally, states could create subsidized employment programs for disadvantaged workers, such as formerly incarcerated individuals, who may otherwise struggle to find stable work.

- Re–envision state unemployment benefits as part of a broader “adjustment” agenda by making benefits more accessible, generous, and indexed to local affordability measures. States can also expand unemployment benefits for residents who are involuntarily working part-time.

- Invest in more universal health and retirement benefits for state residents. This could include enacting paid sick and family leave legislation; expanding Medicaid or exploring state-led public health care options; creating auto-IRA accounts to encourage retirement savings; or creating portable benefits programs for workers with multiple part-time jobs.

Mitigate harsh local impacts

Automation will reshape the labor markets in some communities more than others. Accordingly, governors should redirect and align resources across state agencies to serve the places and the people who are most exposed to economic and technological changes.

- Help all struggling communities reorient their economies toward emerging industries by providing grants and technical assistance to support planning, new staff, and investments that improve connectivity and access to other markets, such as broadband.

- Channel additional state resources toward a select number of mid-size cities that can serve as regional hubs of growth and innovation, focusing on supporting research, commercialization, and tailored training pipelines that meet regional industry needs.

- Prepare state Opportunity Zones to make the most of new investment by aligning existing state education, transportation, or other funds or creating state tax incentives for job training or job creation efforts in these communities.

Ideally, state actions to address the risks posed by automation would be complemented by bold investments at the federal level. However, a robust federal agenda appears unlikely at the moment, meaning that adjustment policy represents yet another area in which state and local actors can lead. In the face of potentially significant disruption, state leaders should take this opportunity to think—and act—big.

Commentary

A governor’s policy playbook to address disruptions from automation and artificial intelligence

March 1, 2019