For more than half a century, the term “the American middle-class,” has served as a political reference to white American upward mobility. This was less an artifact of particular calculations than one of historical experiences and demographic realities. Since at least the 1950s, Americans who were neither wealthy nor “disadvantaged” were, by default, middle class. Who fell into this category? With most African-Americans and Latinos frequently restricted in their access to high quality education, jobs, or homes and because, over the last 50 years, the U.S. has had a majority white population, it could be assumed that the majority of middle-class Americans were white. So, the term “American middle class,” while not historically and intentionally located in a discourse about race, has always inherently been about race, specifically about white Americans. Fast forward to 2016 and two trends have emerged which highlight the degree to which the “American middle class” can no longer serve as an implicit proxy for a group that is predominantly white. First, the demography of the nation is changing rapidly. As our colleague Bill Frey has demonstrated, the U.S. is well on its way to becoming a country where black and brown diversity predominates. In 2017, for the first time, the majority of American children under 10 were black and/or brown. From a purely mathematical perspective, this implies that at some point in the not too distant future, the composition of the American middle class will begin to mirror that of American society as a whole. Second, in the context of greater economic inequality in the U.S., a recent recession, and a 2016 Presidential election outcome that highlighted the plight of low-income white Americans, there is a heightened general public awareness that some previously middle-class whites are no longer “middle class.”

We are then at a political inflection point. Who is the middle class? What does the changing racial composition of the middle class mean for politics, or policy? Our goal here is to provide some empirical grounding to this debate. We describe the changing racial composition of a group we define as the middle class: those between the 20th and 60th percentiles of the income distribution. The middle class according to this definition was predominantly white in 1980, but is only just majority white (56 percent) today, and will be race-plural (what some label “majority minority,” a phrase we dislike) by 2042 (see Note 1). Within the next quarter century, we estimate that whites will no longer be the majority of the middle class, as Hispanics and other minority groups age into the adult population (see Note 2).

who are the middle class?

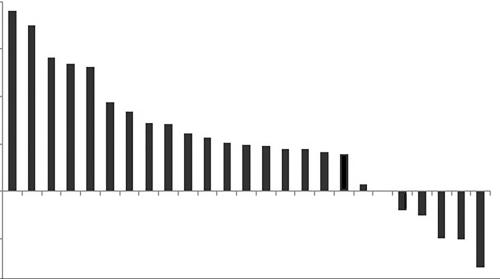

To say that there are many definitions of the “middle class” would be an understatement. Politicians, understandably enough, avoid being too specific in their use of the term: they want as many people as possible to believe they will benefit from a “tax cut for the middle class” or “raising the living standards of middle class” – that is, by ensuring that middle class families achieve common aspirations like home and car ownership, higher education, health and retirement security and time for leisure. This is not especially helpful, given that most Americans, of all backgrounds, share these aspirations. Most Americans define themselves as middle class, although the number varies significantly depending on how the survey question is constructed. Most polling organizations end up dividing the middle class into sub-categories, usually “lower middle class”, “middle middle class” and “upper middle class.” Even then, the “middle middle” is always the most popular choice. Scholars define the middle class in a number of different ways. Many emphasize cultural factors including values and aspirations; others highlight power relations. Researchers with an empirical bent might delineate class by absolute or relative income, or household wealth. For an excellent overview of these definitional questions, see Income Inequality: Economic Disparities and the Middle Class in Affluent Countries, edited by CUNY’s Janet Gornick and Markus Jantii. (We’ll have more to say on this definitional issue in a later piece). For the purposes of this analysis, we consider families whose “head of household” is prime-age (ages 25 to 54) as “middle class” if they fall within the second and third household income quintiles (i.e. between the 20th and 60th percentiles). This group broadly consists of people who are above the official poverty line, but far from prosperous – with incomes ranging between about $30,000 and $86,000. It is important to acknowledge that there is nothing magical about any particular definition. Each comes with advantages and disadvantages. One reason we focus here on this 40 percent of the population is that this group has seen the slowest income growth in recent decades:

To repeat: we do not claim that our definition of the middle class is the definition. We should also be clear that, in part, our definition is influenced by the economic trends described above, rather than being constructed in splendid isolation.

The racial pluralism of the middle class

In 1980, non-Hispanic whites composed over three-quarters of the middle class – 23 percentage points more than they do today. Some of this change is simply due to the increasing size of racial and ethnic minorities across all income groups, some is due to rising incomes, and some due to differing age compositions: the median age of non-Hispanic whites is 43, compared to 29 among Hispanics. The white share of the middle class fell to 55 percent in 2017, and will drop below half to 49 percent within the next quarter-century, according to our calculations:

A note on the projection. We have assumed that the relationship between relative income status and race remains unchanged between 2017 and 2042. The increased racial diversity of the middle class in 2042 is, then, the mechanical result of a broader demographic shift. Many fewer Americans aged between 25 and 54 in 2042 will be white, and many more will be other races and ethnicities, especially Hispanic (see Note 3). These specific estimates should be taken with a few large grains of salt – we did not account for divergent income trajectories, possible changes to immigration policy, or differing life expectancies by race. But predicting such changes would be a difficult undertaking, so we have adopted a simpler strategy.

identity politics versus the middle class: a false choice

There is an important political debate taking place over the plight of the so-called “forgotten Americans” (look out for an important new book from Isabel Sawhill on this topic later this year). Scholars and politicians on both left and right, and in bipartisan groups such as the AEI/Brookings Working Group on Poverty and Opportunity, have wrestled with the challenges facing middle- and lower-income households. Among Democrats in particular, there is a particularly robust argument over the balance between “identity politics” – focusing on the specific challenges faced by groups such as women, racial and ethnic minorities, or LGBTQ Americans – and the white middle or working class. As Columbia Professor Mark Lilla writes:

In recent years American liberalism has slipped into a kind of moral panic about racial, gender and sexual identity that has distorted liberalism’s message and prevented it from becoming a unifying force capable of governing.

On the other side of the debate, Matthew Yglesias of Vox writes (in part in response to Lilla) writes:

People have identities, and people are mobilized politically around those identities. There is no other way to do politics than to do identity politics.

These are important discussions. But we should be careful not to set up arbitrary distinctions. The middle class, at least defined in economic terms, is not white: it is racially diverse; and whites will make up less than half the middle class within a few decades. Any policies that help the middle class will therefore help black and Hispanic Americans as much as whites. The choice between identity-based and class-based politics is, to this extent, a false one.

Notes

- The term “majority minority,” while common, is unhelpful. First, when there is no single racial group in the majority, there is by definition no majority. Second, the phrase lumps together all minorities who are not white into a single category (non-whites), which is inappropriate given the significant differences between these groups. Hence our preference for the term race-plural.

- Note that for the purposes of this paper we follow common practice in referring to Hispanic as a racial rather than ethnic category.

- We look first at the number of individuals within each race/ethnic category under the age of 29 in 2017. We then multiplied these values by the percentage of each race/ethnic category who fell into the prime-age middle class as of 2017. For example, 36 percent of prime-age non-Hispanic whites were middle class in 2017. We multiplied the number of whites ages 0-29 (about 66.2 million) by 36 percent to estimate the number of prime-age whites who would be middle class in 25 years. We then divided this number by the total size of the prime-age middle class (126.2 million) to obtain our final figure of 49 percent.

Commentary

The middle class is becoming race-plural, just like the rest of America

February 27, 2018