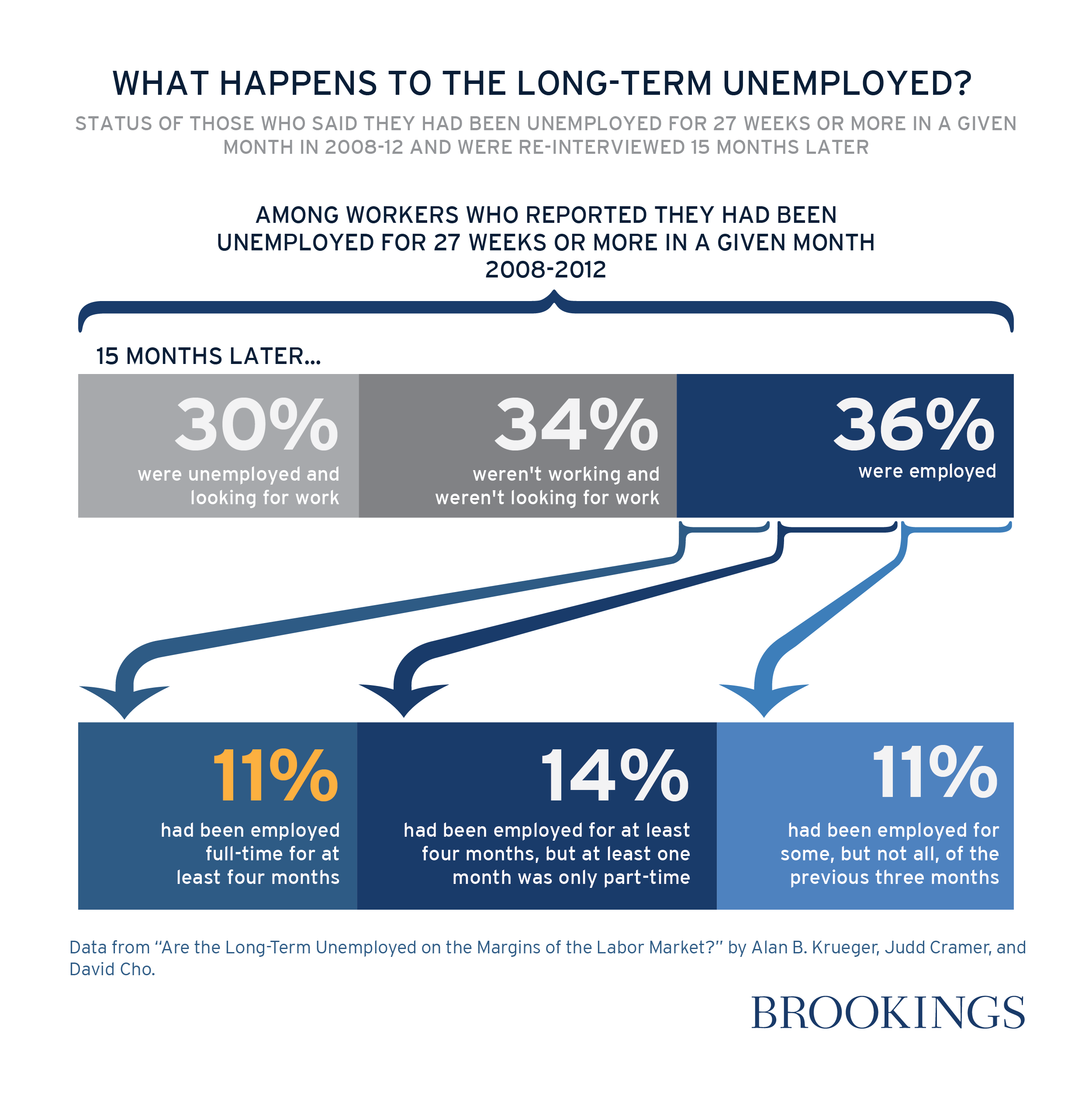

The contemporary American labor market is characterized by persistent, record-high levels of long-term joblessness. Over one-third of all unemployed workers have been looking for work for at least six months. New research from former Council of Economic Advisers chairman Alan Krueger and his Princeton University colleagues suggests that the long-term unemployed are on the margins of the labor force, and exert minimal pressure on both the job market and the macro-economy. This detachment of the long-term jobless has gloomy implications for economic mobility, not only for the individuals who are out of work, but also for their children.

Joblessness, particularly long-term unemployment, has terrible consequences for social mobility. The long-term unemployed earn less if and when they become reemployed. They are in poorer health, and have children with poorer academic performance than similar workers who have avoided unemployment. Communities with a higher share of long-term unemployed workers have higher rates of crime and violence. Simply put, long-term unemployment creates all kinds of hurdles for social mobility—both within-career mobility for a given worker looking to move up the economic ladder through his efforts in the labor market, and across-generation mobility for the children of those workers who have lost their jobs.

What is to be Done?

This week’s new research has two clear policy implications:

- The political circus over the extension of unemployment insurance benefits is hurting American families, and the economy as a whole. Extending access to unemployment benefits helps keep jobless workers in the labor force, because workers must be actively searching for a job in order to continue to receive benefits. Yet House Republicans have signaled an unwillingness to vote on the bi-partisan deal on extended unemployment insurance benefits making its way through the Senate.

- Robust job training programs are an integral part of the solution. Krueger’s data suggest that those unemployed workers who find new jobs are working in fields nearly identical to those from which they were displaced. Jobless workers simply aren’t gravitating toward growing sectors of the economy. If the economy is going to continue to grow, then workforce development and job training programs need to be tailored toward helping out-of-work individuals re-tool their skills to make the leap toward the most vibrant areas of growth, e.g. health care and business services. But the main federal vehicle providing funds for connecting out-of-work Americans to job training, the Workforce Investment Act, is stuck in Congress, and current federal funding levels are well below what’s needed to meet demand.

In the case of both unemployment insurance benefits and job training policy, politics are getting in the way of economically-sound policy. Until and unless Congressional dysfunction—namely Republicans’ refusal to govern responsibly—eases, prospects for the long-term unemployed are considerably poorer than they otherwise would be.

Commentary

Stuck at the Bottom: Long-Term Unemployment and Social Mobility

March 27, 2014