This piece reflects several clarifications and corrections made on February 3, 2023. This piece is part of a series titled “Nonstate armed actors and illicit economies in 2023” from Brookings’s Initiative on Nonstate Armed Actors.

In the almost decade-old civil war in Yemen, the adherence to a cease-fire that began in April 2022 by the Shiite Zaydi Houthi rebels suggests they are now prepared to live with a political outcome to the war that leaves them in control of most, but not all, Yemenis. The Houthis seem prepared to settle for less than complete control of the country. They are in no hurry to reach a deal, however, and the truce could easily break down and return Yemen and Saudi Arabia to combat during 2023.

The Cease-fire and Its Limitations

Beginning in 2014, the Houthis rebelled against the Saudi-backed government that emerged in Yemen from the 2011 Arab Spring. They were joined by former Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh until he broke with them and was killed in 2017.

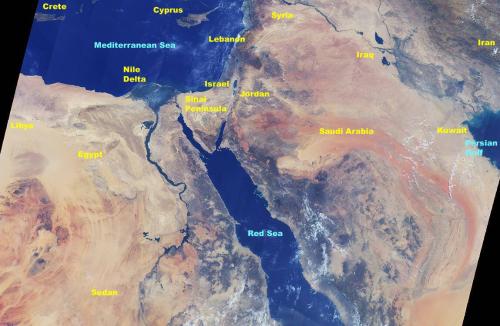

In April 2022, the United Nations negotiated a cease-fire between the Houthi rebels and the Yemeni government and militias affiliated with it, opening the key port Hudaydah to bring fuel and food into the Houthi-controlled north, and the airport in Sana’a for commercial flights to Egypt and Jordan. The truce was extended twice in 2022, but was not extended in October when it lapsed. Nonetheless, both sides are still adhering to the cease-fire for the most part, and to the other terms of the truce like commercial flights to Amman.

The Unresolved External Dimensions

Yemen remains a crucial battleground for external powers. The Shiite Houthis received extensive training and material support from Iran and its ally Hezbollah.

Supporting the Yemeni government and various anti-Houthi militias, the Saudis have seen none of their policy preferences accomplished, despite tremendous expenditures. When the truce began last April, they ditched interim President Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi, whom they installed in power a decade ago to replace Saleh. Hadi is now under house arrest in Riyadh. He was replaced by a seven-man political council that represents the various groups aligned with Saudi Arabia and/or the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The UAE also backs anti-Houthi militias, especially in the southern port city of Aden.

The U.S. policy in Yemen has recently been somewhat successful in conflict management, but not sufficient to halt the crisis and humanitarian catastrophe caused by the Saudi war and the blockade of the north. Shortly after his inauguration, U.S. President Joe Biden gave a major foreign policy speech in which he said the war in Yemen must end. Prioritizing the conflict’s end in U.S. policy is praiseworthy, and by backing the U.N., Biden has achieved some success. He named Tim Lenderking, an experienced diplomat and Middle East specialist in the State Department, as the American envoy for Yemen. More specifically, Biden promised an end to American support for “offensive” military operations by the Saudis, but he did not define what an offensive military action is or whether his admonition applied to the Saudi blockade of Yemen.

Nor did Biden call for a new United Nations Security Council resolution to serve as the basis for his peace initiative. Written in 2015, UNSCR 2216 called on the Houthis to withdraw from all territories they occupied in the civil war including Sana’a, recognize the sitting government, turn over their weapons to the U.N., and end drone and missile attacks on Saudi Arabia. After six years of fighting, not even one of these demands has been met by the Houthis. Biden did not mention that the resolution was deliberately tilted against the rebels by the Obama administration.

The United States Navy also continues to intercept vessels, which it claims are smuggling arms from Iran to the rebels. In December 2021, for example, the Navy reported it had intercepted a vessel with 1,400 AK-47 assault rifles and 226,600 rounds of ammunition. Another was in January 2023. In effect, the United States is a partner in the Saudi blockade of Yemen.

Learning to Live with the Houthis

The tragedy of America’s relations with Yemen is now catastrophic. Two American presidents supported with varying degrees of enthusiasm a deadly Saudi-led war to defeat the Houthis. The blockade has contributed to the deaths of tens of thousands of Yemenis, including thousands of malnourished children. A third U.S. president is now finally trying to end the conflict.

The Houthis are virulently anti-American, but they have done little if any actual harm to Americans or our vital interests. Instead, the Saudi war has allowed them to play the role of patriotic defenders of a small country fighting a rich neighbor with the backing of Washington and much of the Western world. The Houthis are organized along the lines of Hezbollah, their role model and a proven longtime terrorist danger to Americans and American interests. They could evolve into another Hezbollah especially if the truce collapses.

It is time to bring this tragedy to an end. The truce could easily collapse, and the Houthis could resume attacks on Saudi targets, including Riyadh, with their missiles and drones engineered with Iranian help.

Dealing with the Houthis will not be easy even after the war. Their anti-American posture is deeply rooted in the origins of the movement. It is a lingering after-effect of the disastrous decision to invade Iraq in 2003 which led to the Houthis’ radicalization, now compounded by more than six years of American support for a war led by a neighbor most Yemenis hate. Air strikes, blockades, and intentional mass starvation are the characteristics of a war the United States has supported.

On the ground, the Houthis have created a functioning government and highly repressive in the area they control, which includes representatives of other groups. Their Prime Minister Abdel Aziz bin Habtour is from the south and was Hadi’s governor of Aden in 2014-15. Foreign Minister Hisham Sharaf was in several governments starting in 2011. Neither are Houthis. Some 70 to 80% of Yemenis live under the Houthis’ control.

In terms of personal freedoms, however, the Houthis have enforced strict laws on women traveling, requiring written male approval, another reflection of their Iranian patrons’ own policies.

We have lived with other countries with virulently anti-American policies in the Middle East for decades. Unlike Hezbollah and Iran, however, the Houthis have not carried out acts of violence against American interests outside of Yemen. It will not be a friendly relationship, but it does not need to be violently hostile. The urgent imperative is to halt the blockade entirely and get aid to the Yemeni people. A new U.N. Security Council resolution should call for the complete end of the blockade and freedom of movement for Yemenis. That should be America’s priority.

Commentary

The Houthis after the Yemeni cease-fire

January 27, 2023