We should use the Khashoggi crisis as a chance to do what we should have been doing all along, write Daniel Byman and Michael O’Hanlon—namely, to force the Saudis to rethink their disastrous war in neighboring Yemen. This piece originally appeared in the Washington Post.

As the Trump White House comes to grips with the Saudi government’s role in the killing of writer Jamal Khashoggi, it confronts a major dilemma that has bedeviled previous American administrations: How do we punish a country with which the United States is locked in a relationship of profound mutual dependence?

The kingdom needs American military protection, despite having the world’s third-largest military budget and lots of shiny Western weaponry. And the United States, despite the North American shale revolution, still relies on Saudi oil (in the sense that the world oil market cannot function without it). The Saudis are also a vital partner for counterterrorism. For these reasons, American punishment for the murder of Khashoggi, a Post contributing columnist, is likely to consist of the usual wrist-slapping: no high-level summits for a while, a bit less pomp in any official meetings for some time after that and maybe a visa ban or two for complicit individuals. Congress, for its part, may issue a resolution expressing its collective outrage.

That would be a woefully inadequate response. The brazenness of the killing in Istanbul is stunning. Moreover, it targeted an American resident who was a powerful advocate of free speech and political accountability. The even bigger problem, however, is that this murder fits a pattern of outrageous and harmful Saudi behavior. The kingdom’s de facto leader, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, is a brash young man who has by now made many mistakes because of arrogance and inexperience—from his brutal and extralegal “anti-corruption drive” to his abduction of the Lebanese prime minister to his unnecessary public standoff with Qatar. Against this background, the Khashoggi murder is less an exceptional act of recklessness than an emblem of the new normal for the kingdom.

One tempting option would be to stop U.S. arms sales—a measure that could impose pain on Riyadh without disrupting America’s de facto security guarantee, or the world’s unquenchable thirst for Saudi hydrocarbons. Yet President Trump resists this step, arguing that American jobs are on the line.

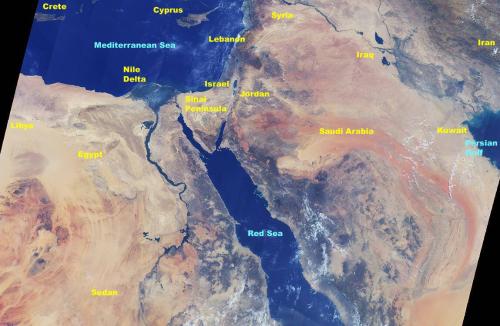

But there’s a natural compromise. We should use this crisis as a chance to do what we should have been doing all along—namely, to force the Saudis (and, ideally, their key ally, the United Arab Emirates) to rethink their disastrous war in neighboring Yemen.

Three years into the Saudi intervention, there is no longer any reasonable argument for believing that what the Saudis are doing will work. Meanwhile, the intelligence support, logistics assistance and specific types of weaponry that we provide Saudi Arabia have made us complicit in all the airstrikes gone wrong and the ensuing carnage among civilians.

Complete victory over the Houthi-led and Iranian-supported forces of northern Yemen is not attainable for Saudi Arabia and its mostly southern and Sunni allies. Nor is it necessary. American, and Saudi, and broader regional interests can be adequately protected by continuing targeted strikes against al-Qaeda elements in Yemen, and reaching some kind of power-sharing agreement that would give Houthi factions more autonomy in northern Yemen with more resources for the rebuilding of the country. An ongoing Iranian presence there, while undesirable, is more tolerable than Iran’s foothold in the Levant. Over time, moreover, a more stable Yemen will need and want Iran less; Tehran thrives on chaos and conflict most of all.

To ensure that Riyadh takes such a more realistic approach in Yemen, Washington should make its military assistance for the war conditional. The United States has considerable influence. Saudi Arabia depends, in part, on the United States and U.S. contractors for intelligence and logistics. Riyadh also values America’s good opinion (and, if anything, values Trump’s support more than it did Obama’s), so it is sensitive to U.S. criticism.

The warring parties could start by declaring a pause in the bombing of Houthi targets and the opening of negotiations, followed by a large-scale infusion of humanitarian aid. The Americans would make it clear to Saudi Arabia that the pace of airstrikes will have to decline (and will reinforce this policy by delivering munitions “just in time” rather than in large batches). American planners should be co-located with Saudis, giving each side veto power over the use of any lethal ordinance.

None of this will solve all the problems between the United States and the kingdom. At least, though, we will no longer be compelled to follow the military lead of a young Saudi prince who has now proven to the world on multiple occasions that his judgment cannot be trusted.

Commentary

It’s time to put the brakes on Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen

October 26, 2018