Turkey’s parliamentary election yesterday was an electoral earthquake. The governing Justice and Development Party (AK Party) saw its share of parliament drop dramatically: it won almost 50 percent of the votes in the 2011 general election and only 40.8 percent on Sunday. This election marks the end of current president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s rise and the beginning of a more pluralistic chapter in Turkish politics.

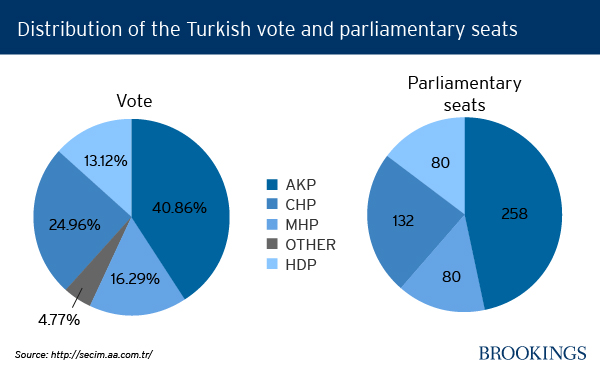

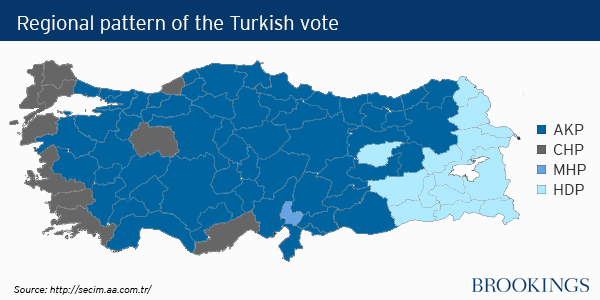

For the first time, the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) surpassed Turkey’s notoriously high electoral threshold with 13 percent of the votes. Earning 80 rather than the expected 60 seats in the parliament, HDP left the AK Party with just 258 seats. This means Erdoğan’s favorite party will be unable to form a government on its own, let alone call a referendum for a new constitution. This came as a big surprise to many observers, since public opinion polls leading up to the election suggested that HDP might fail to clear the 10 percent threshold and the AK Party might win the necessary 330 seats to call a referendum.

Punishing Erdoğan

The Turkish electorate sent two clear messages with this election. First and foremost is that Turkey has had enough of Erdoğan’s haughtiness. There is mounting frustration with the AK Party, and even more so with its former party leader Erdoğan (who became Turkey’s first popularly elected president last August with almost 52 percent of the vote). What explains his drop in popularity?

Erdoğan has displayed an increasingly authoritarian style, disregarding basic democratic values such as freedom of press and expression. Since the AK Party’s 2011 electoral win, he has launched frequent attacks against the independence of regulatory bodies. Leading up to this year’s election, Erdoğan brazenly violated Turkey’s constitution—which mandates the president stay neutral during parliamentary elections—by using state resources to campaign for the AK Party, by denying airtime access to opposition party representatives on state media, and by slamming the opposition at every opportunity. The final straw seems to have been Erdoğan’s interest in transforming Turkey‘s almost seven decades-old parliamentary system into a presidential regime with reduced separation of powers.

This brings us to the electorate’s second clear message, which is that Turkish institutions—such as the judiciary, police, state media organizations, and economic regulatory bodies, including the central bank—should have better stood their ground and resisted Erdoğan’s bullying.

The Turkish electorate also has a history of supporting the underdog. In 2007, the military tried to intervene in politics and preempt then Foreign Affairs Minister Abdullah Gül’s presidency. The government called for an early election and saw its vote share rise from 34 to 47 percent—an increase partly attributable to the military’s meddling. In a somewhat parallel manner, the electorate today appears to regard HDP as the underdog. Erdoğan’s aggressive language against HDP co-chair Selahattin Demirtaş and his callous response to the explosion that killed two and injured over 100 HDP supporters two days before the election seems to have evoked a sympathetic response in favor of HDP. Just as voters punished the military’s hubris in 2007, Erdogan is now being resoundingly punished for his egotism.

The HDP’s inclusive and liberal agenda is also appealing to many liberal Turks. While the Kurdish problem remains the party’s focus, HDP has expressed a desire to become “a nationwide advocate for underrepresented masses who are fed up with the current government as well as opposition parties.” For this reason, the HDP has a 10 percent quota for LGBT individuals and a 50 percent quota for women in its electoral lists. This is incredibly promising, since it suggests that HDP is a party that goes beyond ethnic identity politics. This may be the most important contribution to Turkish democracy at a time when the Middle East is torn by identity and religious politics.

Yet it is important to remember that 40 percent of the electorate still voted for the AK Party, giving it the largest number of seats in parliament. The current composition of the parliament—with 258 seats for the AK Party, 132 seats for Republican People’s Party (CHP), 81 seats for Nationalist Action Party (MHP) and 79 seats for HDP—will force the AK Party to either run a minority government with outside support or to form a coalition.

Both scenarios require compromise, the very element of politics that Erdoğan and the AK Party have made a point of ignoring. Coalition politics will also force the AK Party to refocus on implementing concrete and effective policies to garner support, as opposed to using polarizing language.

In a speech after the results came in, Prime Minister Davutoğlu emphasized that the “national will” had been expressed. This could hint at the beginning of what has been sorely missing in Turkish politics: a political party with a clear vision—founded on democratic values and a well regulated, open-market economy—that can appeal to both the conservative secularists and young liberals. Such a party could arise either from a complete AK Party transformation or from individual politicians breaking away from their own party ranks to unite under a new party. The additional prospects of an early election may very well speed this process.

Two birds, one stone

Sunday’s election, with its 86.63 percent participation rate, allows for rare optimism about Turkey’s democratic future. The electorate demonstrated its commitment to a liberal order and hit two birds with one stone: it removed the gravest threat to Turkish democracy (a presidential regime under Erdoğan), while also encouraging greater diversity in the parliament (with HDP passing the threshold). The public also gave the AK Party a second chance, asking that it revisit its policies of economic and political reform buttressed by EU membership aspirations that had once led to electoral popularity and international prestige. But will Erdoğan and the AK Party listen? Massive challenges remain, and it will be interesting to see how the new parliament addresses the repercussions of the AK Party’s recent rule, namely a declining economy, failed foreign policy, and weakened institutions.

Commentary

Turkish voters send a strong message

June 8, 2015