From April 24 to 28, Kenneth M. Pollack traveled to Baghdad with Danielle Pletka of the American Enterprise Institute. They met with a wide range of senior Iraqi and American officials including Prime Minister Abadi and the heads of all of the other major political factions, as well as the U.S. Ambassador and Lt. General Townsend, the commander of all Coalition forces in Iraq and Syria. Below are his observations and analyses from the trip.

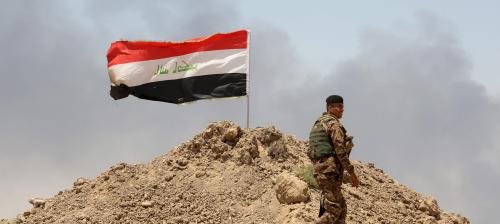

The war against Da’esh

The battle for Mosul continues to drag on, but the Iraqi army continues to win, slowly reducing the pocket held by Daesh (the Arabic acronym for the Islamic State). Advances have been incremental because of a combination of factors: Baghdad’s desire to limit casualties to its own troops, especially the elite Counterterrorism Service (CTS) who have suffered 25 percent casualties overall since the start of the Iraqi counteroffensive; a concomitant desire to spare the civilian population trapped in Mosul by the wrongheaded decision to keep them there; and the badly bifurcated and politicized chain of command that strains coordination among the Iraqi Army, police, CTS and Hashd ash-Shaabi. Nevertheless, both Iraqi and American military leaders averred that the city would be fully under Iraqi control in about a month.

After Mosul is liberated, Iraqi forces will probably continue to push westward from the city to clear the Turkmen city of Tal Afar, a hotbed of Daesh support. They will then drive to the Syrian border to shut off the main route of infiltration from Raqqa to Mosul. With northern Iraq secured, Baghdad plans to shift its forces back to the southwest, to finish clearing the Euphrates valley, where Iraqi troops have reached Haditha, but still have a considerable stretch of Daesh-controlled towns out to al-Qa’im and the Syrian border. Once that major corridor has been recovered, the plan is for Iraqi forces to finish off the last Daesh stronghold in Iraq, at Hawija in north-central Iraq, just southwest of Kirkuk. Hawija is a difficult city, both geographically and because of its strong support for Daesh (and for al-Qa’ida before that).

Those with real understanding of Iraqi and Coalition military plans all believe that the war is likely to continue through the end of 2017, although in the form of smaller military operations and with less fanfare than the Mosul campaign. Moreover, those Daesh personnel who have been able to flee Mosul have largely melted back into the Jazira desert of northwest Iraq, where Daesh first began to infiltrate Iraq in early 2013. There is a widespread belief that many Daesh fighters—the majority of whom are Iraqis and Syrians—hope to continue a guerrilla war even after their conventional armies have been destroyed and their major territorial holdings liberated. Of course, their ability to do so will depend overwhelmingly on the level of tacit support they receive from Iraq’s Sunni community, which in turn is likely to be determined by the course of political and economic developments in Iraq.

It is for that reason that it remains disconcerting that neither Iraq nor the U.S.-led Coalition appear to have developed concrete plans for the political reintegration or economic redevelopment of Mosul and Ninevah province. Iraqi officials simply could not answer questions regarding what they intended to do in Mosul after liberation, only that past and present political arrangements were inadequate and “something different” would have to be created. Likewise, on the economic front, the Iraqis seemed hopeful that the United Nations Development Program and the Coalition would provide much (if not all) of the know-how and labor for resettling displaced persons, restarting basic services, and repairing damage. The Iraqis appear to regard the liberation of Ramadi and Fallujah as blueprints for action in Mosul, but most non-Iraqi government sources see both of those operations as having left much to be desired, and note that Mosul is a far bigger challenge than either Ramadi or Fallujah.

Iraq is an inefficient society and after nearly 30 years of war, sanctions, and devastation, Iraqis have learned to tolerate a high degree of deprivation. Consequently, the inevitable problems that are likely to flow from this lack of planning and preparation at Mosul may have only a limited impact on the state of Iraqi politics, at least for some time. On the other hand, Iraq remains a fragile state that is still suffering from nearly a dozen years of on-and-off civil war. As I (and others) have been warning for nearly three years, the absence of well-structured and resourced plans for the political, economic, and social reconstruction of Mosul could lead to unrest, and potentially even help push Iraq back into civil strife. The fact that so many Iraqis are tired of fighting, that the Iraqi Sunni community appears to have decided that siding with Daesh in 2014 was a mistake (as was embracing al-Qa’ida in 2005), and the naturally high Iraqi threshold for deprivation many create a grace period of months or perhaps even a year or two for the government to get its act together. However, it is impossible to know for sure.

A Respite for the Iraqi Economy?

To watch it in action, the Iraqi economy would seem to be slowly gaining speed. Life in the city of Baghdad has improved noticeably since I was last there in March 2016. The city felt vibrant. There are fewer checkpoints and those we saw appeared to be manned by members of the Iraqi security services, not the Hashd ash-Shaabi militias as in the past. Billboards thanking Iran for saving Iraq from Daesh had been removed. The stores appeared to be doing reasonably good business throughout central Baghdad. Goods are flowing in. There are people in the streets and lots of cars on the road. While traffic is bad, it is not crippling. What’s more, Iraqis treat it as an inevitable annoyance and rarely let their anger get out of hand. All of this reflects a sense among Iraqis that things are economically alright. No one grumbled about the availability of anything, not even electricity yet. Of course, spring is the best season in Iraq because the days are long and the weather is mild so that people don’t need either their lights or their air conditioners for most of the day.

Moreover, the Iraqi oil sector is moving along at a good clip. Production reached 4.6 million barrels per day (mbd) last month, although exports were kept to just 4 mbd to remain within the current OPEC quota. By most accounts, the Iraqis plan to keep expanding production to 5 mbd by the end of the year, although they insist they will continue to respect the current OPEC deal, which seems likely to be extended through the end of 2017. The Iraqis claim that they will simply store the extra oil they pump beyond domestic consumption needs, which amounts to about 0.5 mbd. However, that may prove difficult since much of Iraq’s new oil storage capacity is not yet connected to its pipeline network.

Similarly, Iraq’s financial sector is stable for the moment, but remains problematic and could worsen in the future. The recent financial infusions from the World Bank, IMF, Coalition, and U.S. loan guarantees have collectively taken the pressure off the Iraqi budget. This has been hugely important. Most civil servants (who represent an excessive percentage of the work force) are getting paid, albeit at lower levels than before 2014. The government is also able to pay key costs for many of its contracts, which has similarly restored salaries for many in the private sector who live off government contracts.

But the loans will prop up Iraq’s finances for only a few years. Iraq can’t keep borrowing at this rate, and the U.S., IMF, and World Bank won’t let it. They are monitoring Iraqi debt carefully to ensure that Iraq doesn’t push itself into crisis by overborrowing. Moreover, as a result of corrupt currency exchange policies, Iraq is suffering from a crisis of liquidity. There simply isn’t enough money in circulation and the Iraqi central bank is part of the problem, not the solution. As a result, many Iraqis simply do not have money to purchase anything beyond basic needs, and there is virtually no domestic investment because it is far more profitable for the banks to trade currency than to loan money to entrepreneurs. In addition, because of the widespread corruption in the bureaucracy, successful entrepreneurs are systematically fleeced by civil servants unless they have a powerful political figure who can protect them—although in that case, the protector typically robs them to an only slightly lesser degree. As an additional symptom of this problem, we did hear quite a bit of grumbling about high prices, the lack of service, and corruption. It hard to know which is more frustrating: that goods and services are not available, or that they are but they are unaffordable.

In short, Iraq’s economic situation is tolerable at present, but it will be hard to sustain beyond the next 2-3 years. Iraq is going to have to make some more dramatic moves to address the structural problems in its economy or else (absent a major increase in oil prices) it may find itself right back in a financial mess.

To their credit, some within the Iraqi government are thinking in smart and creative ways about how to make such moves. Prime Minister Abadi has made this a priority, and the economic reform planning team in his office is looking at further subsidy cuts, pro-growth policies, and anti-corruption measures including the introduction of extensive “e-government” practices that would also improve efficiency. The Ministry of Planning is pushing forward a scheme to build several major roads, including a new super highway from Baghdad to Amman, Jordan that would include tributary roads to connect the many towns of Anbar province, and financing for business development to turn the entire network into a major economic pathway, something like an Iraqi “Route 66.” Other Iraqi technocrats are pushing for a major overhaul and upgrade of the banking system, to shut down the corrupt currency exchange practices, create an electronic banking system, and push cash back into the economy to revive both consumption and investment. However, all of these plans remain in their infancy and all will be major lifts for Iraq’s weak bureaucracy and paralyzed political system. Given Baghdad’s record over the past 14 years, no one should bet heavily that any of them will come to fruition without major assistance from the international community.

Meanwhile, southern Iraq is reportedly facing growing problems. As I have noted in the past, the absence of Iraqi security forces has left the south largely in the hands of local, extra-governmental armed groups. Tribal militias, organized crime rings, and branches of the Hashd ash-Shaabi militias, especially Iranian-backed groups such as Asaib ahl al-Haq, Badr, Abu Khataib Hizballah, and Muqtada as-Sadr’s Sarayat as-Salaam, have all taken over large chunks of southern Iraq. They have established protection rackets there that are further siphoning money out of the hands of consumers and business owners, scaring off investment, and causing damage from low-level fighting. The ports of Basra and Umm-Qasr are said to be badly corrupted by these militias. One senior Iraqi security official told us flat out that, “the south is no longer under the government’s control.”

So far, the pervasive militia control has not affected oil production in the south because the international oil companies continue to pay off all of the militias, but they are said to be worried that if the situation continues to deteriorate, their personnel and infrastructure may be targeted by the militias either for greater blackmail or as a result of turf battles among them. There is a widespread hope that after Mosul is liberated, Baghdad will begin shifting some Iraqi army and police formations south to restore order before things get any further out of hand.

The Political Maelstrom

As always in Iraq, it all comes down to the politics. Despite the military progress and the new buoyancy in the Iraqi economy, the political system remains largely deadlocked. At the moment, that is mostly because all of Iraq’s leaders are fixated on the upcoming elections. Iraq will hold national elections in the spring of 2018, probably in April. Although provincial elections are scheduled for late this year, they are likely to be postponed until either February or April of 2018, and in the latter case would simply be tacked onto the national elections, in part to save money.

Prime Minister Abadi remains the candidate to beat. Abadi is enjoying a significant degree of popularity because of Iraq’s military successes and its (relative) economic improvement. In addition, Abadi is largely seen as nationalistic and non-sectarian. However, his re-election is far from guaranteed. Many of his rivals, and even some of his supporters, complain about his inability to get the political process to do anything or to curb the rampant corruption. (Although both they and I would note that those are Herculean—if not Sisyphean—tasks). Perhaps of greater importance, because his current popularity is partly based on the success of the military campaign and the current economic buoyancy, it could prove ephemeral. We simply do not know if a year from now, Iraqis will still be looking to reward the prime minister who led the war on Daesh or if the economy has once again cratered. In those circumstances, Abadi may have to start delivering on at least some of his plans to fight corruption and reform the Iraqi economy and political system to pull out an electoral win.

Because of the sense that the frontrunner is vulnerable, intra-Shi’a rivalries continue to intensify. Maliki himself is maneuvering energetically behind the scenes. He has given up on removing Abadi in a vote of no-confidence because of the unequivocal support of the United States for Abadi, and is instead focused on unseating him in the election. Many believe that Maliki truly has decided that he cannot be prime minister again and will simply try to play kingmaker, a notion bolstered by the fact that he has been able to remain powerful (and alive!) even out of office over the past three years, something he had doubted. Hadi al-Ameri, the de facto leader of the Hashd ash-Shaabi and a key ally of Iran, also looms large as a potential candidate. Either before or after the election, some combination of Abadi, Maliki, and Ameri, the three strongest Shi’a candidates, may opt to band together and agree to make one of them prime minister to avoid fracturing the Shi’a electorate. Right now, much of the game appears to be whether all or some combination of two of them will be able to forge such an alliance.

Meanwhile, other political parties are jockeying on the sidelines, looking to ally with one or another of the main Shi’a parties, or to band together themselves if the three major blocs remain divided and so create an opportunity for other groupings. For instance, Ammar al-Hakim and the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (ISCI) are trying to position themselves as a moderate compromise among one or more of these factions, and perhaps a refuge for Shi’as sick of all the infighting among them. Ammar is the nominal head of the Iraqi National Alliance, the umbrella party of all of Iraq’s Shi’a groups, and he has used this to try to advance an agenda for national reconciliation that both Sunnis and Shi’a voters disaffected by the major blocs and eager to put the civil war behind them might flock to. In contrast, former prime minister Ayad Allawi is threatening to sit out the elections altogether because of various ongoing debates about the fairness of the impending election. In particular, Allawi (among others) is concerned that key Shi’a politicians have packed Iraq’s Independent High Election Commission and this will result in a tainted election. Of course, Abadi’s moderation, non-sectarian approach, and military victories have stolen much of Allawi’s natural constituency from him. Thus, Allawi may calculate that it is better to sit out the election on grounds of principle and look for an opportunity to return later on if Abadi fails to deliver in a second term.

Yet the elections are a long way off, especially in Iraqi political terms. A potential crisis therefore revolves around what, if anything, can get done this year before the elections. With all of Iraq’s major political figures focused on the election and all of them determined to prevent their rivals from winning a major victory during that time, there is a terrible potential for inactivity over the next 12 months. The danger, of course, is that Iraq’s problems are unlikely to remain static during this time. Down the road, Iraqis may rue having simply frittered away this critical period when Daesh was on the ropes, people were tired of fighting, and the economy was propped up by external assistance.

Along these lines, the issue of the Hashd ash-Shaabi militias continues to hang like a sword of Damocles over everything. It was striking how often the issue of the Hashd ash-Shaabi came up in all of our conversations, but typically with vague assertions that “something” had to be done to sort out the problem, mostly indicating an unwillingness on the part of the speaker to voice his preferred solution because of the political sensitivity of the issue. Under the new Militia Law, the Hashd have been brought formally under government control. What’s more, they have largely obeyed Prime Minister Abadi’s commands since then. As Hadi al-Ameri himself noted to us, Hashd units have been sitting at the Tal Afar airport for months, waiting for the order to move into the city and clear out Daesh, but they have not done so because Abadi has not yet given the order. However, the new law cuts both ways, legalizing the existence of the Hashd in ways that its leaders hope to exploit to turn it into a co-equal arm of the Iraqi Security Forces, like the Revolutionary Guard in Iran. Most other members of the government want to see the Hashd disbanded and its personnel incorporated into the Army and Police, or else put to work on infrastructure repair projects. And inevitably, there are those calculating whether to oppose or support the Hashd depending on how it would help their political fortunes. And as always, Iran looms in the background, likely hoping to preserve the Hashd as a Hizballah-like force that not only will help execute their will inside Iraq, but project power beyond it.

As I suggested above, it is almost certainly going to require considerable prodding and support from external actors, particularly Washington, to help Baghdad overcome all of the political incentives for inaction during the period before the elections. The United States remains the only external power with the potential willingness and ability to push and help Iraq to take the steps that it otherwise won’t. While Iran remains a very influential actor in Iraq—arguably still the most influential albeit far less than at its peak in late 2014—it has shown no inclination to help Iraq move in constructive directions. What’s more, U.S. influence has grown very significantly as a result of America’s invaluable military and economic assistance over the past two years. Thus, the potential is there for Washington to lend such support. The only question is whether the Trump administration is willing to do so, a question that remains unanswered at this point in time.

Commentary

Dispatch from Iraq: The anti-ISIS fight, economic troubles, and political maelstrom

May 5, 2017