In the weeks leading up to the 2023 Superbowl game, San Francisco 49ers’ defensive player Charles Omenihu was allowed to play in the game against the Philadelphia Eagles after being arrested and charged with domestic violence on January 23. His coach, Kyle Shanahan, said at the time: “We feel very good about letting the legal process take care of itself and don’t feel we should kick him off the team at this time.” Omenihu played 38 defensive snaps in the 49ers’ 31-7 loss to the Philadelphia Eagles in the National Football Conference Championship Game on Sunday on January 29, 2023.

Gender-based violence is not limited to the National Football League (NFL) or even to the sport of football. From youth leagues to pro teams, stories of gender-based violence are all too common in the world of sports. High-profile incidents and allegations of abuse have occurred in a variety of college sports including hockey, gymnastics, and swimming and professional sports like the NFL and Major League Baseball (MLB).

Gender-based violence—including sexual and domestic violence as well as child sexual abuse—in SportsWorld is epidemic. SportsWorld, a term coined by Earl Smith, refers to the notion that sports is more than the games played on the field or court. It encompasses all of the attendant structures including travel, television and broadcast rights, and highly lucrative contracts for both players and coaches. Gender-based violence is prevalent in SportsWorld for many reasons; SportsWorld is a mirror of society, and many sports have a culture that promotes traditional expressions of masculinity, including aggression and sexual exploits. The primary reason for gender-based violence in SportsWorld is because the institutions and people that make up SportsWorld fail to hold offenders accountable. This includes players, coaches, physicians, and trainers. When acts of violence are reported, even amidst mounting evidence, they are allowed to continue to coach, play in games, and provide medical care.

As faculty at the Center for the Study and Prevention of Gender-Based Violence at the University of Delaware, we conduct research that focuses on violence in SportsWorld. To better understand the prevalence of gender-based violence in sports—as well as to catalog the consequences for those who are accused of and perpetrate it—we built a unique dataset.

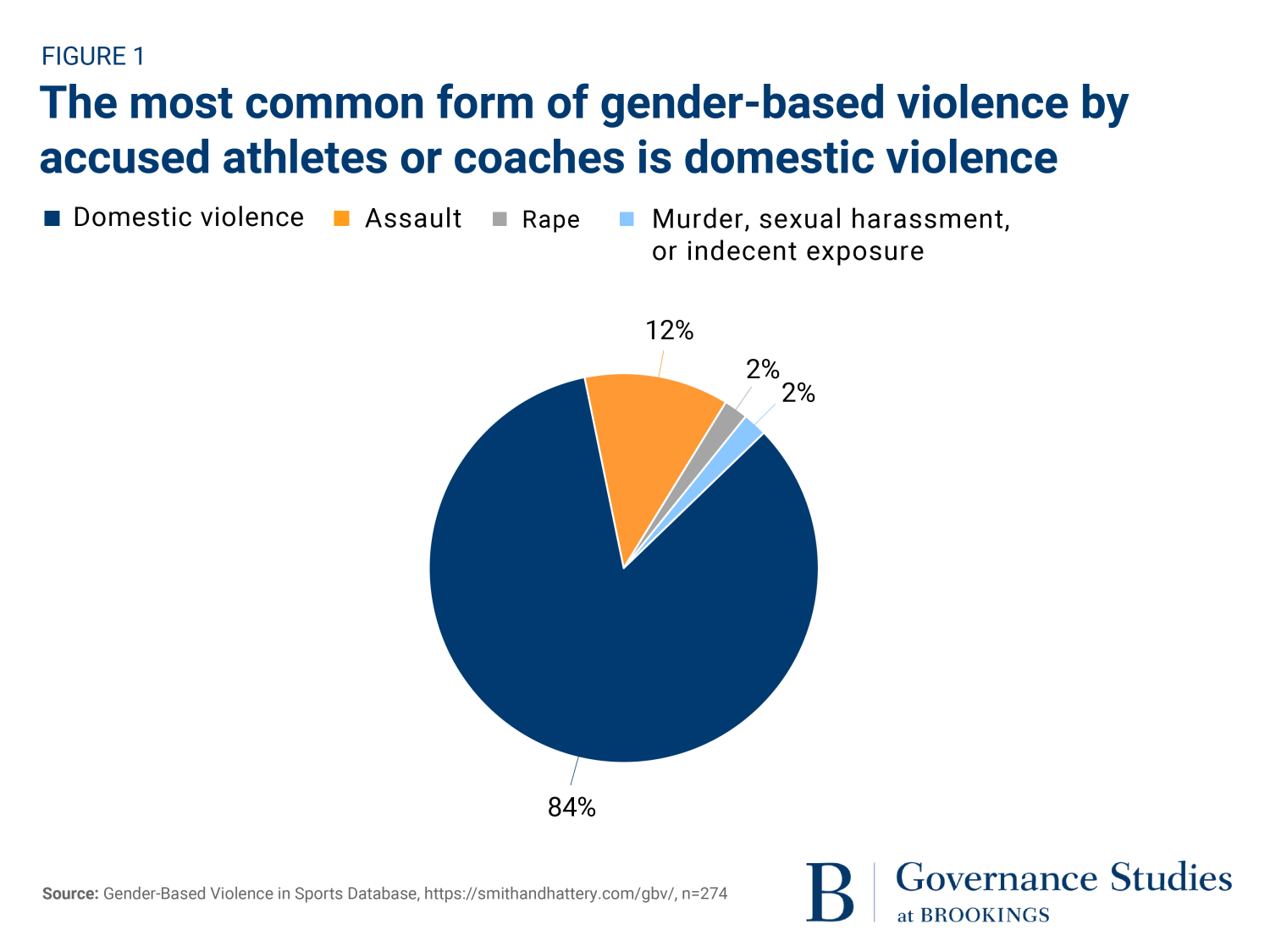

The Gender-Based Violence in Sports Database catalogs more than 270 individual cases, dating from 1974 to the present, that involve active and retired college and professional athletes and coaches in just about every major sport, including football, basketball, baseball, hockey, boxing, mixed martial arts, motor sports, tennis, track and field, swimming, and gymnastics. Even though many sports are represented, football stands out. Just over half of the 274 cases involved athletes who play college or professional football. Cases are derived from publicly available sources including newspapers and websites that index reports, arrests, charges, and citations for any incident of gender-based violence.

Key Findings

- We found that in over 75% of the cases, regardless of whether the perpetrator was charged, arrested or convicted, the accused athlete or coach was allowed to remain on the team and continue to work or compete. Stunningly, many of the individuals who continued to play or coach were charged, arrested, and/or convicted of a serious violent crime.

- Many of those arrested, charged, and convicted are serial abusers: 15% of athletes in our database were arrested more than once for acts of gender-based violence.

- It’s not just high-profile athletes who are not held accountable. In fact, among the cases in our database, coaches and staff remained employed, often for years after the first accusations were made.

This was the case with Larry Nassar, who practiced sports medicine at Michigan State University and also worked for USA Gymnastics. Nassar was convicted of sexual abuse in a case which saw hundreds of girls and women come forward. The first incident was reported by a parent and dates back to 1997. But Nassar continued to provide medical services to athletes at Michigan State University and USA Gymnastics for another 20 years until news of the abuse was reported in the Indianapolis Star in 2016. and he was fired by Michigan State. It was a similar story with U.S. Olympic Swimming and national team coach Mitch Ivey and former USA Swimming coach Andrew King. King was eventually convicted of multiple counts of child molestation while Ivey was banned for life from the sport’s governing body after years of harassment allegations.

Why Existing Policies Don’t Work

When athletes, coaches, physicians, and trainers are not held accountable, it puts others at potential risk for victimization. Many organizations have policies and processes for addressing athlete and staff misconduct, including colleges and universities and professional leagues—most notably, the NFL. Yet, despite the presence of these policies, athletes, coaches, and staff are rarely, if ever, held accountable and even fewer in any meaningful way.

In 2014, in response to criticism, the NFL toughened its stance toward players accused of domestic violence with a new personal conduct policy that included an automatic six-game ban for a first violation of the policy. Crucially, the policy would hold players accountable “even where the conduct itself does not result in conviction of a crime.” Yet, a 2017 investigation by the Bleacher Report found that since the implementation of the 2014 revisions to the personal conduct policy, this six-game ban had been enforced in only two of the 18 cases in which players faced domestic violence allegations.

Our analysis reveals that even when sanctions are applied, those suspensions are often reduced. This was the case with NFL players Ben Roethlisberger and Greg Hardy, both of whom had lengthier initial suspensions that were eventually reduced to four games in response to challenges by the NFL Players Association. Speaking to the New York Times, Alissa Leeds, a former executive with the NFL, noted, “Everything’s excused in the name of football.”

Recommendations

Overall, we find that policies are largely ineffective because they give too much power to the players, coaches, teams, and leagues to override the recommendations they lay out. Therefore, we recommend legislation that would require accusations of gender-based violence (and all crimes) that are reported directly to an organization (e.g., a college or university student conduct office, the league offices of the NFL or Major League Baseball, or USA Gymnastics) be immediately referred out to the criminal legal system. Removing people with a vested interest in the success of the athlete or coach from adjudicating accusations of criminal behavior is a good next step in creating accountability measures that hold the potential for reducing gender-based violence in sports.

The database is available for journalists and researchers interested in addressing gender-based violence in sports. It can be accessed at the Center for the Study and Prevention of Gender-Based Violence website.

Commentary

Ineffective policies for gender-based violence in sports result in a lack of accountability

April 4, 2023