The COVID-19 crisis presents the world with a huge challenge: Everyone and everything is affected, and the response has to be both quick and global. While it is first and foremost a health crisis, it is also an education crisis, an employment and economic crisis, a crisis of hunger and a poverty and, in some countries, a crisis of governance and political stability. According to World Bank estimates, the global impacts will be profound and long-lasting. For developing countries with much larger populations at risk, fewer resources, and less capacity, the pressure to develop innovative approaches, test them quickly, and deliver them at scale is especially great.

In mid-April 2020, we issued a call to participants of the Community of Practice on Scaling Up Development Outcomes (CoP) requesting contributions to a special newsletter dedicated to the challenges and implications for international development of the COVID-19 pandemic. This is a cross-sectoral and diverse CoP with one objective: understanding the operational and policy requirements for effective scaling development impact in middle- and low-income countries. With over 600 participants from over 250 organizations, and with active working groups on agriculture and rural development, health, nutrition, education, youth employment, social enterprises, monitoring and evaluation, and scaling in fragile states, we thought it was especially well-positioned to help developing countries engineer an effective response to the health, economic, and social impacts of the coronavirus.

We were not disappointed. We received 40 submissions—some on more than one initiative. The responses spanned subjects including agriculture and rural development, education, health, nutrition, social enterprise, and youth employment. In early May, we distilled them into in a newsletter. This blog summarizes their insights and highlights some promising initiatives. Five messages deserve special attention:

1. Identify, disseminate, and evaluate promising innovations in real time.

Numerous initiatives are underway to identify innovations and innovators, including the COVID-19 Innovation Hub (C19IH) developed by USAID, DFAT, KOICA, and the Results for Development Institute. C19IH has featured 700+ deployable to inspirational innovations categorized across 12 COVID-19 response areas, and 80+ funding opportunities to help innovators find follow-on funding. To facilitate rapid learning, the C19IH has started to visualize COVID-19 innovation data and trends and welcomes partnerships to analyze and capture lessons learned about innovations adapting and scaling in response to COVID-19, and beyond. In parallel, the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), together with “Team Europe” partners including the EU Commission, other EU member states, tech companies, and civil society, mobilized a global hackathon #SmartDevelopmentHack for scalable innovations to address the COVID-19 crisis and its aftermath.

2. Revisit the role of digitalization and IT in reaching scale during crises.

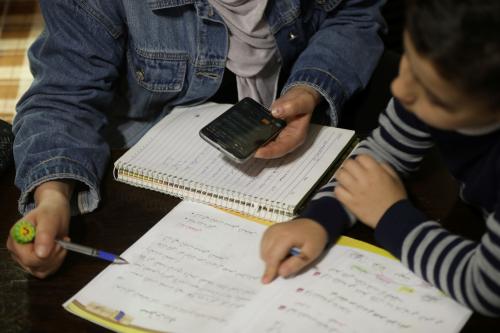

The role of IT was dramatically demonstrated by keeping billions connected with each other during lockdowns. But it is also highly relevant for specific development areas, including for schooling, as demonstrated by Educate! in its efforts to integrate digital learning during the crisis and beyond; by CRS in its distribution of millions of bed nets to fight malaria in Benin during the pandemic; by the Working Group for scaling in agriculture in its call for increased rural internet access; and by CGD with its report on digitalization of social protection in South Asia as a means to support the poor during the crisis.

3. Differentiate responses between developing countries and high-income economies.

As colleagues from Yale University’s Y-RISE emphasize, there are critical differences between high-income and developing countries both with respect to the effects of the pandemic and cost-effective responses to it. Sierra Leone’s experience with the Ebola crisis may well be more pertinent for some low-income countries than the experiences of South Korea or New Zealand in responding to COVID-19. In particular, the barriers and enabling factors to scaling up innovative approaches can be completely different in developing countries as compared with high-income countries because of differences in demographic characteristics, the level of informality in the economy, fiscal space, institutional capacity, ITC and information infrastructure, and effective mobilization networks. Some contextualized approaches are highlighted in the newsletter.

4. Recognize sector specificities.

The contributions illustrate how responses can be tailored to specific sectoral circumstances. Here are some examples:

- In health, fighting COVID-19 requires country-appropriate testing approaches, applying lessons from the Ebola crisis (e.g., Save the Children), addressing mobility and logistical constraints in maintaining health care and health supply chains (e.g., E2A, EvidenceAction, ExpandNet), and integrating IT solutions (e.g., CRS). In all countries, it is important to ensure that other health problems (including vaccinations) do not get neglected. But these problems are not the same in every country; perhaps the only common response is the need to shore up primary health systems for children and women (e.g., Co-Impact).

- For agriculture and food security, solutions are beginning to emerge to restructure value chains, support rural enterprises, and assist the rural poor (ARD Working Group, IFAD, HarvestPlus, Nourishing Africa, et al.).

- In education, a range of resources and strategies have emerged virtually overnight for supporting children while out of school with remote education technologies and alternatives to school meals. There is a growing list of innovative approaches for getting children back to school as soon as it is reasonably safe to do so, while integrating the lessons from remote learning into the classroom (Education Working Group, Educate!, Millions Learning, Room to Read, et al.).

- The youth represent a major demographic cohort in many lower income countries and—while less susceptible to direct health effects of the virus—are likely to be especially hard hit by the economic fallout from the crisis. Youth employment opportunities have particular importance (MSI, USAID, Youth at Work, World Learning).

- For social, small, and medium enterprises there are heightened risks of survival, and various initiatives are underway to assist them during the crisis and afterward (Social Enterprise Working Group, CASE).

- Community engagement was noted by many commentators as being especially critical during times of crisis to help protect and rebuild social capital (GOAL). The role of women in communities deserves particular attention and support (CARE).

5. Incentivize aid agencies and implementing organizations to adapt.

Contributors to the newsletter stressed a variety of areas where development agencies need to adapt. Agencies with procedural and programmatic flexibility and/or decentralized delivery systems are likely to be better at adapting, especially in responding to the loss of mobility. Some established international development agencies (e.g., IFAD) are adapting their delivery modalities to disburse greater amounts of financing, as well as speed up and increase the impact of their support. Front-line implementers will be called upon to assume unfamiliar roles such as teachers and agricultural extension agents delivering health messages, support, and supplies in remote rural areas (Millions Learning, Syngenta Foundation). Planning and monitoring and evaluation systems will need to be radically transformed to meet the demands of pace, scale, social distancing, and uncertainty (MSI).

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Developing countries can respond to COVID-19 in ways that are swift, at scale, and successful

June 4, 2020