The deadly flood in Louisiana and the severe fire season in southern California in the United States are part of a worldwide rise in climate-related floods, storms, droughts, and wildfires. Their occurrence, alongside epic floods in China, drought in India, forest fires in Canada, and heat waves and floods in United Kingdom discredit opposition to climate action from a number of influential quarters.

Many policymakers view the financial cost of dealing with climate change as a drag on economic growth. But the mounting damages from climatic disasters make it clear that it is the other way around: Climate inaction impedes growth. Moreover, many in developed nations have the mistaken notion that climate disasters only happen in faraway places. True, there have been more fatalities in developing countries, but deadly disasters are increasingly striking developed countries. Furthermore, some politicians, perhaps looking at long-run climate models, still have the false sense that climate change is a future phenomenon. But Earth’s 2015 temperatures were the warmest since records began in 1880, with 2016 set to be warmer.

The ferocious Louisiana floods were the worst natural hazard in the United States since Superstorm Sandy four years ago. In one part of Livingston Parish, more than 31 inches of rain, the daily average for all of the U.S., fell in 15 hours. More than 60,000 homes were destroyed and 13 people were killed.

California’s latest forest fires proved disastrous as the Blue Cut Fire in the Cajon Pass in San Bernardino destroyed 105 homes and 213 other structures. It was a week of extensive losses when wildfire raced through southern California, where a five-year drought had left brush land bone dry.

These catastrophes received considerable media attention and have become part of the U.S. election politics. But few in the political discourse make the connection between the rise in such disasters and runaway climate change. This neglect in an election season misses out on a huge opportunity to press for action.

At least part of the rise in hazards of nature must be attributed to climate change, although as in the case of linking monetary policy to inflation, it is hard to pin any specific event to a specific cause. Even so, the evidence that more atmospheric carbon emissions go hand in hand with higher temperatures and more frequent climatic disasters is unmistakable.

Using data for countries across all regions over the past four decades, we find that people’s exposure to bad weather and their vulnerability to calamities matter to making hazards of nature disasters. But we find that the intensity and frequency of the hazards themselves are critical too. The latter have been on the rise in association with a greater concentration of carbon in the air and a rise in sea-level temperatures—also contributors to the frequency of intense climate disasters in Asia-Pacific countries.

Sending this message makes all the difference to policy. If the floods and fires ravaging the U.S. were purely a natural phenomenon, the best we can do is to continue relief, rehabilitation, and reconstruction. But if the rise in carbon emissions is partly to blame, it will not be enough to simply mop the floor after it gets flooded: We must also turn off the tap. This means climate action will need a big boost to keep warming well below 2 degrees Celsius.

At last December’s global meeting on climate action in Paris, countries committed to so-called intended nationally determined contributions (INDCs) to help achieve this goal. But new research published in Nature finds that while these contributions will lower greenhouse gas emissions, the median scenario will still result in a warming of 2.6–3.1 degrees Celsius by 2100. Clearly, we need to overshoot the current INDCs.

This will require three main steps. First, the enormous scientific and recent economic research that has been done should be used to inform election debates. In democracies, issues that are not taken up as priorities in elections season get short shrift afterward. Climate action needs to become a top election issue.

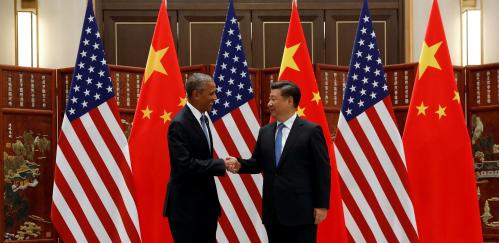

Second, the U.S., China, India, Russia, Japan, Germany, U.K., and others must meet and overshoot their INDCs. Most importantly, they should aim for much lower carbon emissions by phasing out the burning of fossil fuels aggressively and switching to renewables rapidly.

Third, this is the time to put in motion financing models that would facilitate a switch to a low-carbon growth path. Public funds need to be mobilized with great urgency: The $100 billion reaffirmed at the Paris meeting is grossly inadequate. The private sector needs to innovate and leverage to make the use of climate financing viable.

What were once in a lifetime disasters are now happening with alarming frequency–and no policy issue threatens development as urgently as climate change.

Vinod Thomas is the Former Director General of Independent Evaluation at the World Bank and at the Asian Development Bank. Email: [email protected]

Commentary

The political priority for climate action

September 12, 2016