Last week Alphabet, the parent company of Google, emerged as the world’s most valuable firm with a market capitalization of $531 billion. One of the company’s “moonshots” are driverless cars, which could revolutionize mobility.

My home country, Germany, has a particular affinity for cars. One out of every seven jobs in the country is directly or indirectly dependent on the car industry. For many of my compatriots, owning a car and driving it fast on the highway, is a core dimension of our identity. More broadly, in OECD countries, the ability to drive almost anywhere, at any time, and with relatively high comfort is taken for granted.

Can it get any better or have we already exhausted the potential for productivity growth that derives from mobility? In 1899, U.S. patent and trademark commissioner Charles Holland Duell proclaimed that everything that could be invented had been invented. Is the car industry merely an illustration of this theory or rather its starkest disproof in today’s economy?

When discussing the future of mobility, it is important to remember that, in today’s economy, value is no longer synonymous with physical output. Today’s (intangible) technology giants, such as Apple, Google, Microsoft, and Facebook are valued between $300 and $500 billion and they are also the world’s most valuable companies; by contrast, Germany’s (tangible) industry leaders such as Siemens, Daimler, and BMW are all below $100 billion.

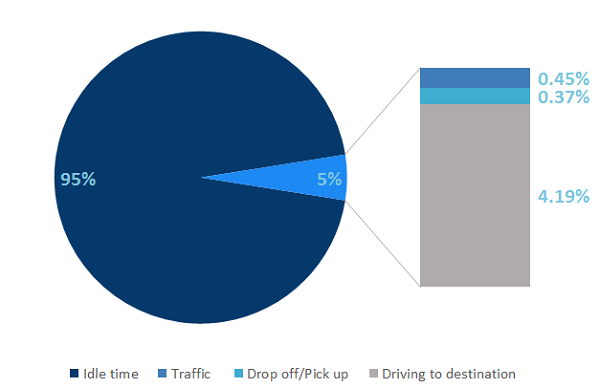

The next frontier is the full integration of the digital world with the automotive sector, which can generate a new wave of productivity gains. Where will those gains come from? While increased personal mobility has allowed us to be more efficient in so many ways, there is still considerable scope to improve the way “mobility inputs” are deployed. Just think about this simple fact: Even though cars are among the most expensive things most people own, they sit idle most of the time. The average car spends only 5 percent of the time on the road, of which 1 percent is wasted either in traffic or on commuting back from dropping someone off (see Figure 1). Most of the time, cars are parked, occupying valuable space, especially in cities.

Figure 1: Cars are only in productive use 4 percent of the time.

Source: Calculations by Anastasia Shegay based on U.S. National Household Travel Survey (NHTS) and the 2015 Urban Mobility Scorecard.

Imagine we could bridge this gap between the supply and demand of mobility in a way that cars are actually on the road most of the time and not in parking lots. In a world of driverless and shared cars, the number of vehicles could be reduced dramatically, at least by two-thirds, not to mention the potential to avoid loss of life and injuries.

In this new world, there will be fewer cars but greater mobility options. You will be able to order the car of your choice, at the time you need it, straight from your mobile. You will be charged on a trip basis and no longer worry about the administration and management of the car (insurance, repairs, parking, etc.). At the macro level, our economies will dramatically increase their productivity, while also protecting their resources and allowing citizens to reclaim their cities.

But what about the pleasure of driving, the thrill we get from pushing the pedal and feeling the acceleration? Most likely the personal car of today will end up the same way as the “personal horse” of yesterday: as a recreational activity, reminiscent of a past that has been overtaken by modernity.

Commentary

Digital cars: What drives productivity in developed countries?

February 10, 2016