As even casual observers of American politics know, contemporary presidential nominating contests begin with the Iowa caucuses, followed by the New Hampshire primary. Less well known are their different roles in determining the eventual winner. Candidates finishing well back in the pack in Iowa have gone on to secure their party’s presidential nomination. By contrast, since the beginning of modern nomination process in 1972, no one finishing lower than second in New Hampshire has ended up as his party’s nominee. The conventional wisdom is that there are three tickets out of New Hampshire. If history is our guide, there are only two.

Some examples will illustrate these points. Let’s start with the Democrats. In 1972, George McGovern finished third in Iowa behind Edmund Muskie and an uncommitted slate but went on to win the Democratic nomination after finishing second to Muskie in New Hampshire. In 1988, the eventual Democratic nominee (Michael Dukakis) finished third in Iowa but first in New Hampshire. In 1992, Bill Clinton finished fourth in Iowa, with only 3 percent of the vote, but scored a dramatic second-place finish in New Hampshire that opened the door to his eventual nomination.

Turning to the Republicans: George H. W. Bush finished third in Iowa in 1988, behind Bob Dole and Pat Robertson. Two decades later, John McCain finished fourth, trailing Mike Huckabee, Mitt Romney, and Fred Thompson.

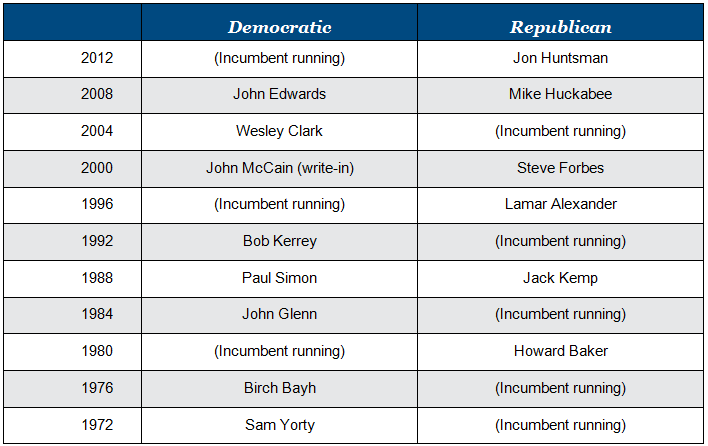

By contrast, here is a table of third-place finishers in New Hampshire over the past forty years:

As you can see, there’s not a single winner among them.

History is not destiny, of course. But the record suggests that if Jeb Bush were to finish outside the top two slots in New Hampshire, his candidacy would be in jeopardy, despite the infrastructure he has built and the money he has raised. Similarly, if Vice President Biden were to enter the race and former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton ended up trailing both him and Bernie Sanders when the votes were tallied in New Hampshire, the southern “firewall” she has built might not be enough to contain the conflagration.

The past four decades underscore why so many long-shot candidates are betting the farm on breaking through in New Hampshire—and why the putative frontrunners have so much to lose in the Granite State.

By contrast, much of the breathless commentary in the hours after the Iowa caucuses may turn out to be misplaced. Despite the fact the Iowa is one of the few remaining swing states, the activists who dominate its caucuses are not a microcosm of the voters who will end up determining the nominees of the two parties. As frontrunners such as George H. W. Bush in 1988 and insurgents such as Bill Clinton in 1992 have demonstrated, a weak showing in Iowa is no guarantee of subsequent failure.

Commentary

For 2016 candidates, all eyes should be on New Hampshire

September 9, 2015