Editor’s Note: As part of the 2014 Midterm Elections Series, we’ve asked experts from the ten states with competitive Senate races to answer six questions in a spotlight on each race, providing perspective on the dynamics in the state as we head toward Election Day. In this post, Jerry McBeath looks at the Alaska Senate race between Senator Mark Begich and Dan Sullivan.

Although Alaska entered the union as a Democratic state, since the 1964 election it has voted Republican in presidential, most federal and state elections. Nevertheless, Alaskans pride themselves on their individualism and independence from national forces, including political party appeals. In 2014, of the 509,011 registered voters in the state, 54 percent are either nonpartisan or undeclared voters. Still the Republican Party, with 135,910 registrants, strongly outnumbers the Democratic Party, with only 70,469; it has a stronger organization and more elected officials than the minority. The incumbent senator in 2014 is Mark Begich, a Democrat, finishing his first term in federal office.

This post touches on five topics: the macro campaign issues and how they have been handled, specialized issues, SuperPACs in Alaska, turnout concerns and media gaps. At the outset, the campaign to date, one week before the election, has been more about candidates then issues, and in this respect resembles many previous Alaska high stakes campaigns. This includes the race Mark Begich won in 2008, when the incumbent, Ted Stevens, had just been convicted on charges of corruption (later dismissed by the U.S. Attorney General).

Issues, Handling

1. Sullivan’s short residency in Alaska

For the Begich campaign, Republican, Dan Sullivan (U.S. marine for 20 years, Lt. Col. in the marine reserves, former state attorney general and commissioner of natural resources) did not seem sufficiently “Alaskan.” Begich was born in Anchorage. His father, Nick, was Alaska’s Democratic congressman when his plane crashed without trace in 1972. Sullivan, on the other hand, was born in Ohio and spent most of his life outside Alaska. In 1994, he married an Alaskan (Julie Fate, daughter of a Fairbanks Native leader, Mary Jane Fate; her father was a well-known Fairbanks dentist and Republican legislator), and moved to the state in 1997.

The Alaska Democratic Party alleged that Sullivan, who worked in DC during the Bush (II) administration (as head of the International Economics Directorate for the National Security Council and then an Assistant Secretary of State), had been dishonest: he received tax breaks from Maryland for his $1.1 million Bethesda home (claiming it as his primary residence), while voting in Alaska elections as a permanent resident. The state of Maryland supported Sullivan, who deflected criticism of his short residency by stating that Ted Stevens, the state’s longest-serving and most acclaimed U.S. senator, had been a resident of Alaska for a relatively short period before his first electoral win, and that he would be a better “fighter for Alaska” than his opponent.

2. Begich’s effectiveness in the Senate

The Sullivan campaign hammered Begich as an ineffective legislator. He had authored only one piece of legislation in his first term, and that was insignificant: the re-naming of a courthouse in Anchorage. They repeated critical reports of Begich as “lazy” and rising through the Senate hierarchy “at the speed of a mastodon trapped in a glacier.”

The Begich campaign responded by pointing out he’d gained plum assignments (seat on Senate appropriations), and had cooperative relationships across the aisle, ties with Republican colleagues that were better than those in any other divided state delegation. Both Representative Young and Senator Lisa Murkowski criticized Begich for claiming credit he did not deserve. Murkowski’s office even issued a “cease and desist” order, claiming Begich’s ads made “false statements” and were unethical for picturing her without asking permission. Soon thereafter Murkowski endorsed Sullivan.

Many observers thought the charges and counter charges were petty. Both Young and Murkowski earlier had praised Begich’s work when Eielson Air Force Base seemed likely to lose a squadron of F-16s, with a potentially devastating impact on interior Alaska’s economy. The senator held up the promotion of a three-star general until the military reconsidered. Acknowledging the work Begich had done, the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner unexpectedly endorsed him for re-election (10/24/14), saying his committee assignments and seniority were critical to the state’s interests.

3. Federal overreach

The final complex problem was the role the federal government plays in Alaska, which often surfaces as an issue in both state and federal elections. The Sullivan forces called Begich a “loyal footsoldier of President Obama and Harry Reid, and probably the most effective cartoon used by this campaign pictured Begich as a puppet whose strings were pulled by the president. While on the stump in cities and towns, Sullivan railed against the EPA, the federal permitting process stalling Alaska growth and above all else, the Affordable Care Act (aka Obamacare), for which Begich cast the “deciding vote.”

As a Democrat, Begich had few options other than to distance himself from a president whose re-election campaign in 2012 collected 14 percent less of the Alaska vote than Mitt Romney’s effort, and who in 2014 was nearly as unpopular as was George W. Bush in the 2006 mid-term elections. Right after the primary, Begich claimed that he would be a “thorn” in President Obama’s backside. Incessantly he mentioned that he was a senator for all Alaskans, and had voted with Republican Senator Lisa Murkowski 80 percent of the time (as opposed to the 97 percent voting support he allegedly gave the Obama administration).

In the nation’s critical Senate races, Begich was like other Democrats, embarrassed by association with an unpopular president. In a campaign debate, Begich said health care reform had helped 37 percent of Alaskans gain access to health care, but his campaign spent little time defending the Affordable Care Act.

Specialized Issues

The Begich campaign also emphasized three other issues on which his positions contrasted favorably with Sullivan for significant groups of voters. All Republican primary candidates held conservative positions on abortion; Begich pointed out his more liberal views, perhaps attracting greater support from women. While Sullivan supported development of the Pebble mine near Bristol Bay, Begich opposed it, gaining the support of Alaska’s fisheries interest. Begich has far stronger labor support than Sullivan, and consistently has supported an increase in the minimum wage. Sullivan first opposed and then supported an increase, doubtless to ensure he did not lose the labor vote entirely. The Begich campaign could not take much advantage of this apparent waffling, because opposition researchers working for the Crossroads GPS SuperPAC said Begich was a hypocrite for claiming to support higher wages for women while paying female staffers in his office considerably less than men. On a per capita basis, Alaska has the largest veteran population, and both candidates sought their votes.

Three propositions will be on the November 4 ballot in Alaska, and they likely will have the effect of increasing turnout. The candidates have not taken strong and contrasting positions on the marijuana proposition; and as mentioned, their positions on the minimum wage proposition have become similar, but unions heavily support Begich. Only on the Pebble mine proposition is there a sharp contrast, and this likely will benefit Begich.

SuperPACs

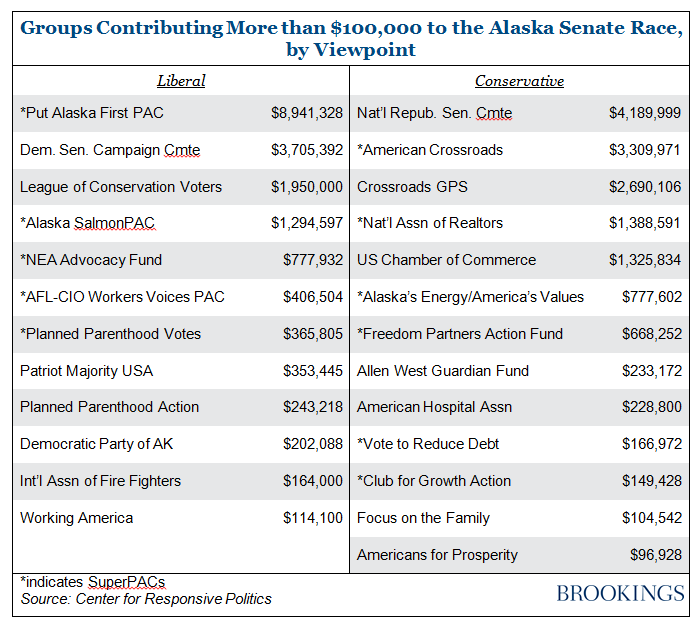

The Center for Responsive Politics reports that SuperPACs collectively have contributed far more to the Alaska Senate race than ordinary PACs, political parties or individuals. Below is a list of all groups contributing more than $100,000, by viewpoint, liberal or conservative.

Altogether, SuperPACs contributed the lion’s share of spending (contributing for or against campaigns in ideologically predictable ways), with the Begich campaign drawing nearly $2 million more than the Sullivan campaign (as of 10/27/14). The value of Begich’s incumbency is reflected in this number.

Turnout

Several weeks before the November general election, the Alaska Division of Elections opened 208 early voting stations (161 of which were in rural areas). In both the 2008 and 2010 Senate elections, early voting was thought to have increased the number of Democratic voters. A week before the November general election, campaign staff and many volunteers commenced get-out-the-vote (GOTV) activities. As mentioned, it is expected that the three propositions on the ballot will boost voting enthusiasm of younger and less engaged voters, so that turnout may exceed the 2010’s 52 percent.

The Begich campaign has paid special attention to the rural vote, because a majority of residents are Alaska Natives who typically support Democratic candidates for office. The campaign established 16 field offices with a total staff of 90 as compared to the Sullivan campaign, which established 5 only (and a staff of 14). Begich called this intensive effort his “ground game,” designed to eke out a plurality against predictions of most polls after the Republican primary that gave Sullivan a lead of 1-2 points.

Trust the Media?

In general, the U.S. media do a good job of covering political news in Alaska. In elections with a national impact, and events such as John McCain’s selection of Sarah Palin as his running-mate in 2008, national print media (e.g., LA Times, New York Times), newsmagazines (Newsweek, Economist), and electronic media send reporters to America’s North. Certainly, accounts in national media have captured most interesting episodes of the high stakes Senate campaign and the last-minute transformation of the gubernatorial election contest, when Independent candidate Bill Walker joined Byron Mallot, the Democratic candidate, in a unity ticket to oppose incumbent Republican Governor Sean Parnell. The only noticeable gap in coverage is treatment of saturated-media weary voters and the high undecided vote in the U.S. Senate race (6.3 percent) so close to the election.

Commentary

2014 Midterms: Key Issues in the Alaska Senate Race

October 29, 2014