The Taliban government’s decision earlier this year to ban girls from attending secondary school (grades 7-12) sent shock waves across the world. The outcry against this decision has been loud—within the country and internationally—and has set back hard-gained advances in educational access over the last two decades. While it is clear that Afghans value education, schooling has historically been a source of conflict. The Taliban’s actions were a sordid manifestation of this larger problem.

The relationship between education and conflict has become a growing focus for academics and practitioners of international education development over the last two decades. Practitioners have focused on teaching “peace education” and signing declarations such as the Safe Schools Declaration and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (Afghanistan is a signatory to both). However, neither of these two initiatives has made much difference in practice. I contend that unless national and international education development programs systematically address larger societal problems through a dialogue brokering local concerns with global aspirations and view education as an ecosystem rather than a single model, education will continue to be a cause of conflict rather than a source of unity, especially for fragile states, like Afghanistan.

The closure of girls’ secondary schools

On August 15, 2021, the Taliban took control of the country from the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. The takeover resulted in the temporary closure of all schools until mid-September when the Taliban announced the reopening of primary schools for boys and girls but that secondary schools for girls would remain closed—pending further deliberation. Girls’ secondary schools remained closed for the next six months. There was a ray of hope when the Taliban announced the reopening of girls’ secondary schools at the beginning of the new academic year. Thousands of eager girls showed up in their uniforms for the first day of school on March 23, 2022, but their joy was short-lived. After a few hours, the school doors were closed, and the girls who had arrived at school with smiles returned home with tears in their eyes. Three months have passed since the closures, and there is still no clear pathway for opening these girls’ schools or what that opening would look like.

As Afghans and international stakeholders grapple with how to come to terms with the new regime in Kabul, ending the relationship between education and conflict should be on top of their agenda.

The sudden and chaotic reversal in closing girls’ schools by the Taliban Supreme Leader, Mulla Hibatullah Akhundzada, even surprised many other Taliban government officials. This last-minute reversal seems to be a political calculus related to balancing aspirations for global legitimacy with maintaining the hard-line image with the rank and file domestically. The Taliban leadership sees the issue of girls’ education as political leverage with the international community and within their base. Mulla Hibatullah Akhundzada likely did not think opening girls’ secondary schools would result in greater legitimacy for his regime with the international community, but it would certainly water down the Taliban’s hard-line brand and result in a loss of support from the base.

The rural-urban divide

Education has been at the center of power struggles in Afghanistan since the introduction of modern schooling in the early 1900s. There is a long history of national and international actors manipulating the education system for political purposes (read more here and here). The primary source of contention has centered around balancing global forces for modernization with local desires to maintain religious and cultural identities.

Unfortunately, girls’ schooling has served as the litmus test for both sides in this struggle—not because the conservative and rural populations believe that girls should not be educated—but because of the symbolic power of schooling. Girls going to school have become the strongest symbol of modernization on one side and foreign domination through globalization on the other.

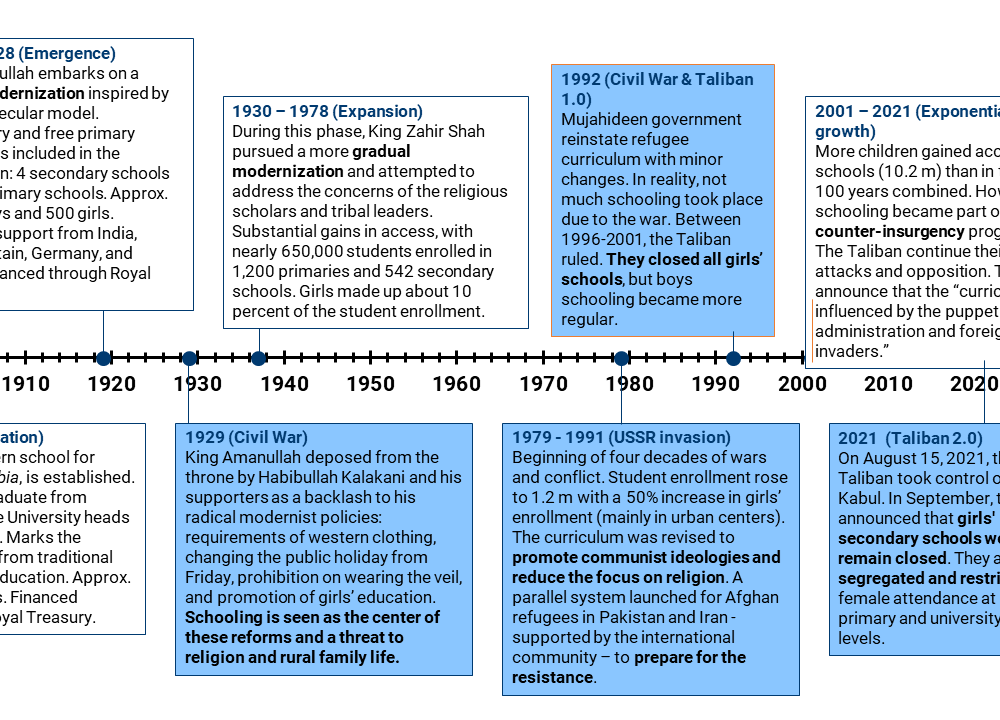

This tension has manifested in a continuous cycle of expansion in modern schooling, followed by violent conflict (Figure 1). All the while, national and international educational development efforts have focused almost exclusively on tactical approaches to expand access to schooling and have failed to address the relationship between schooling and conflict.

Figure 1. History of modern schooling in Afghanistan

Source: Author’s analysis.

Historically, there has been a noticeable divide in Afghanistan between rural and urban communities and how they view schooling and education. Generally, students of the madrasa system (who tend to be from rural communities) have sounded the alarm that schools are a mechanism to undermine religious and cultural identities, while urban elites have championed schooling as a force of modernization and economic prosperity. The Taliban’s closing of girls’ secondary schools is the latest example of how education—and girls’ schooling, in particular—has become a proxy for larger socio-cultural, political, religious, and economic conflicts related to balancing traditional and modernist aspirations.

Balancing global and local aspirations

Modern schooling is a global phenomenon that is primarily a byproduct of Western religious, political, and economic forces. The non-Western world has predominately adopted (and scaled) schools through colonization, modernization efforts, and other globalization forces. While some countries have successfully negotiated the relationship between their local educational aims and practices with that of modern schooling, other countries have struggled to find this balance. The misalignment of the traditional educational systems and modern schooling, along with the dynamics of globalization, donor dependency, and local politics of power and identity, have made schooling a source of conflict. Afghanistan unfortunately—like many other fragile states—falls in the latter category.

Previous research has shown that fragmented and siloed educational systems with disparities in purpose, access, attainment, and educational quality, as well as inequalities in the distribution of resources, fuel violence. To make education a source of unity rather than a source of conflict, I propose that national and international policymakers focus on three distinct areas as a starting point to tackle the underlying sources of conflict:

- Move away from a single delivery system perspective of schooling and embrace a larger ecosystem perspective that combines multiple pathways. Conducting a mapping exercise that outlines the areas of divergence and potential sources of conflict between the various educational pathways within the country—including parallel systems like formal and community-based schools, supplementary programs like private courses, and competing educational models like madrasas and private schools—seems like a good starting point.

- Provide a platform for dialogue within the country—and between the local and global actors—to discuss and identify the larger socio-political sources of division. This can help build the national consensus on the aims, objectives, and purposes for education. A national strategy championed by local and national figures that engages all stakeholders through in-person meetings and traditional as well as social media can be a good strategy to start this dialogue.

- Embark on an overarching and comprehensive system redesign to address local and global aspirations. Designing a new national credentialing system for primary and secondary education that allows students to combine elements of the whole educational ecosystem toward a unified national graduation degree is a practical first step.

The relationship between education and conflict is complex and multifaceted and does not lend itself to easy solutions. The suggestions above are meant as a starting point in the right direction. In Afghanistan, the previous government had embarked on the journey toward a system redesign, but unfortunately the cycle of violence stopped those efforts before they could come to fruition. As Afghans and international stakeholders grapple with how to come to terms with the new regime in Kabul, ending the relationship between education and conflict should be on top of their agenda.

Commentary

The relationship between schooling and conflict in Afghanistan

Lessons for balancing local and global aspirations

June 21, 2022