For those working in the field of women’s sexual and reproductive health and rights, contemplating the 2017 International Women’s Day, which celebrates women’s achievements globally, brings mixed emotions. With international declarations such as the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals including gender equality and women’s rights as central to national and global development, there is hope. However, as is evident in the various forms of gender violence that continue to beset women across the globe, this Women’s Day must also be a day for reflection.

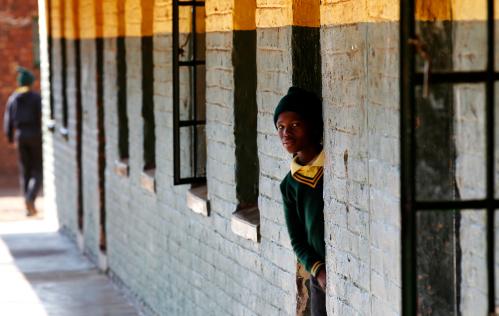

I have been working with groups of girls in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa for the past two years. Our work, using participatory visual methods, including photovoice, digital storytelling, and participatory video, focuses on identifying and addressing gendered violence in communities. In a recent workshop, one of the girls informed us that the group had prepared a play that they would like to perform. When asked what it was about, she described it as “our way of making [the researchers] understand what our lives as girls are like in this community.”

The narrative in the short skit revolved around a practice known as Ukuphuma KweZintombi (the “Coming out Ball”). For this festival, girls and young women dress up in their best clothes (both western and Zulu attire), often bought or made especially for the occasion. On the day of the festival, held in an open field, the girls perform local songs and parade around the field. This is for unmarried men as well as those with polygamous intentions to choose a wife from among the girls. In the skit performed by the girls in our project, a young woman is selected for marriage against her will, but with the enthusiastic approval of her parents, and is taken to the man’s home as a young wife. The skit ends with her reminiscing about dropping out of school due to forced marriage, her early child bearing, living in poverty, and with an HIV positive status.

From female genital mutilation, virginity testing, early and forced marriages, and abductions, girls and young women in many communities globally continue to face harmful traditional practices. As is evident in the above example, in spite of a rights-based, post-apartheid constitution, South Africa is no exception. With the ushering in of the new constitution and the bill of rights in 1996, many in the country believed that not only would existing harmful traditional practices be a thing of the past, but that those that had died would remain buried. Some of these, including virginity testing, have resurfaced, purportedly to protect girls, for example, against early pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections, including HIV. Alternatively, these practices aim to keep girls “pure” until marriage. However, unplanned teenage pregnancies continue to be high (even though they are lower than in other sub-Saharan African countries), and while HIV infections seem to be stabilizing, new ones continue to be negatively skewed against girls and young women. With complex links to gender inequality, and the violence that characterizes it, girls and women find it impossible to decide whether, when, and who they marry, have sex and/or bear children with. Exercising their sexual and reproductive choice often exposes them to sexual and physical violence, or worse, to death at the hands of a partner, or because of backstreet abortions. Further, poverty and unemployment often forces women to choose between control over their own bodies and feeding their families.

Research suggests that boys (and men) believe that girls and women “ask for it” (rape and other forms of gender violence against them) and that they are vectors of diseases responsible for infecting males. Sadly, girls and women in these communities have come to “accept their lot,” believing that the violence they suffer is their fault for refusing to have sex with a partner/husband, wearing a short skirt, drinking alcohol, etc. Similarly, international surveys suggest that in many sub-Saharan and Asian countries, both men and women often believe that a man is justified to beat his wife in certain situations.

A related explanation for high rates of gender-based violence is linked to the poor socio-economic conditions, poor infrastructure, and lack of resources in many communities and schools in sub-Saharan Africa. For example, poor sanitation and the lack of proper and adequate toilets in homes and other social spaces has been linked to high rates of sexual violence against women and girls. In South Africa, scholars have suggested that if the country solved its sanitation problem, it would go a long way toward addressing sexual violence in communities.

Harmful cultural practices, largely informed by unequal gender norms, expose girls and young women to negative health, education and economic outcomes. The unequal gender norms, which render girls and women unequal in intimate and social relationships, mean that they are unable to negotiate and make decisions about their lives and bodies. This negatively affects their chances of completing their education.

To turn things around, we need intervention at three levels. At the individual level, oppressive and discriminatory values that inform the ways in which boys and men relate to women must be transformed. Similarly, programs that work with girls and women as oppressed or marginalized groups must aim to transform their internalized oppression and empower them to contest injustice and unequal gender relations. At the social and relationship level, interventions must aim to provide spaces and opportunities for contesting and changing unequal norms. Finally, at the institutional level (including the family, schools, health facilities, etc.), programs that seek to create and maintain equal or inclusive environments must be created. With these interventions in place, the social norms that create and maintain the harmful cultural practices that push girls out of school may be eliminated.

Commentary

‘Cultural’ practices continue to force girls out of school: Time to act decisively

March 7, 2017