Children learn from the books they encounter in their homes, schools, and libraries. The lessons they take from these books shape their beliefs and the future selves they will grow into. These lessons come from many dimensions of books; one such dimension which is particularly salient to the reader is who is and is not present in each picture and passage. The presence or absence of different characters teaches children societal norms about who gets to exist in what spaces. This matters for the children themselves—shaping their beliefs about themselves and their place in the world—but may also help shape their views of what spaces others of different identities may inhabit.

The problem is that it is hard to know, systematically, how race and gender are represented in the books we use to teach our children. Parents and teachers cannot possibly read every available book before they choose which books to give or suggest to their children or students, much less librarians, superintendents, or policymakers. These actors face a dauntingly large number of choices and often turn to external sources for help. A common source many look to for such guidance is endorsement of merit by a third party, such as recognition from national awards like the Caldecott and Newbery Medals. Indeed, our analysis of book purchases, library checkouts, and internet searches shows that winning these awards leads to a substantial increase in the number of children who read them. This then raises the questions: What messages about race and gender do these specific books convey, via representation, to the children who read them? And how can we measure similar representation in the other content considered for children’s use?

Using computer vision and natural language processing to measure representation in children’s books

This is where we come in. Our solution, which we describe in a paper forthcoming in The Quarterly Journal of Economics, is to use computers—specifically tools from the computer science subfields of computer vision and natural language processing—to measure representation in children’s books. Our approach develops a series of new tools, and combines them with other existing tools, to measure various features, including race, skin tone, gender, and age, of who is represented in the images and text of curricular materials. These tools are powerful and can measure many possible features of characters. We focus on bringing together tools that can measure the representation of these features of characters in both the text and the images of the books we wish to study.

Our analysis shows that these tools can be rapidly and cost-effectively applied to a wide range of curricular materials. They allow us to quickly and cheaply measure if and how people are represented in a large number of books.

We apply these tools to over 1,000 children’s books which have been recognized by a century of children’s book awards. Our analysis focuses on two main sets of books targeted towards children 14 and under. One set receives recognition for their literary or artistic value. These are books that are recognized by the prestigious Newbery and Caldecott awards. We call this the “Mainstream” collection of books because of their influence. The second set of books are recognized for both their literary or artistic value and for how they highlight experiences of specific identity groups. These include awards such as the Coretta Scott King Award, which highlights books centering experiences of Black individuals, and the Rise Awards which recognize books that center women. We call the books in this group the “Diversity” collection.

Despite significant progress, representations of race and gender in children’s books continue to lag

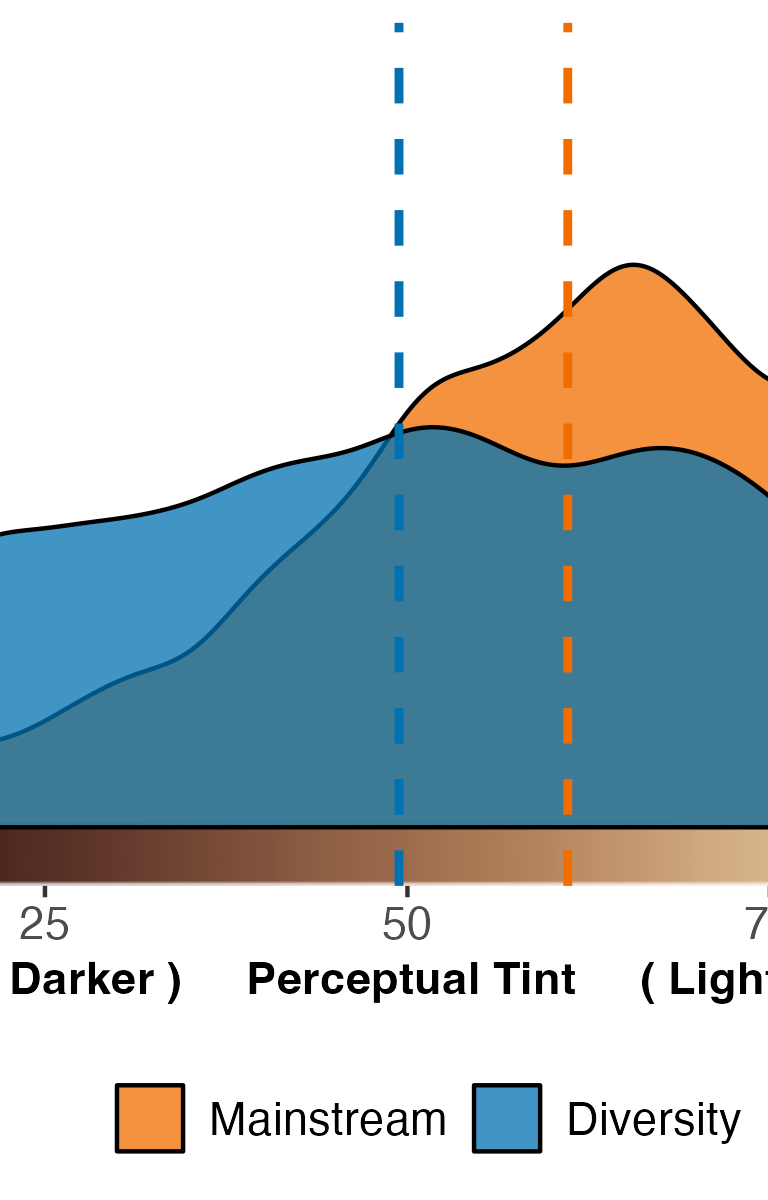

We first show how race and gender have been taught to children via these books’ images and text, and how this has changed over time. Our findings reveal some enduring patterns and others that indicate change. We find that characters in the Mainstream collection are consistently depicted with lighter skin than those in the Diversity collection. You can see how the two distributions vary in this figure: the Diversity collection, outlined in blue, clearly has a darker average skin tone than the Mainstream (see Figure 1). What’s more, it also has more variance—and thus diversity—of skin tones represented than the Mainstream collection.

Figure 1. Distribution of skin colors by human skin colors in Mainstream and Diversity collections in children’s literature

Note: This figure shows the distribution of skin color tint for faces detected in books from the Mainstream and Diversity collections. The mean for each distribution is denoted with a dashed line.

Source: Author’s calculations. See paper for additional details.

In Figure 2, we show that this difference between the two collections holds true even after conditioning on the race of the person being shown.

Figure 2. Distribution of skin colors by human skin colors in Mainstream and Diversity collections in children’s literature by character’s race

Note: This figure shows the distribution of skin color tint by the predicted race of the detected faces in the Mainstream and Diversity collections.

Source: Author’s calculations. See paper for additional details.

In other results, we show that children are more likely than adults to be shown with lighter skin, despite there being no definitive biological foundation for this that we are aware of. In other words, lighter-skinned children see themselves represented more often than do darker-skinned children. This result, unlike those previously, holds for both collections. That is, even in books recognized for highlighting the experiences of Black children, darker-skinned children are less likely to see themselves represented.

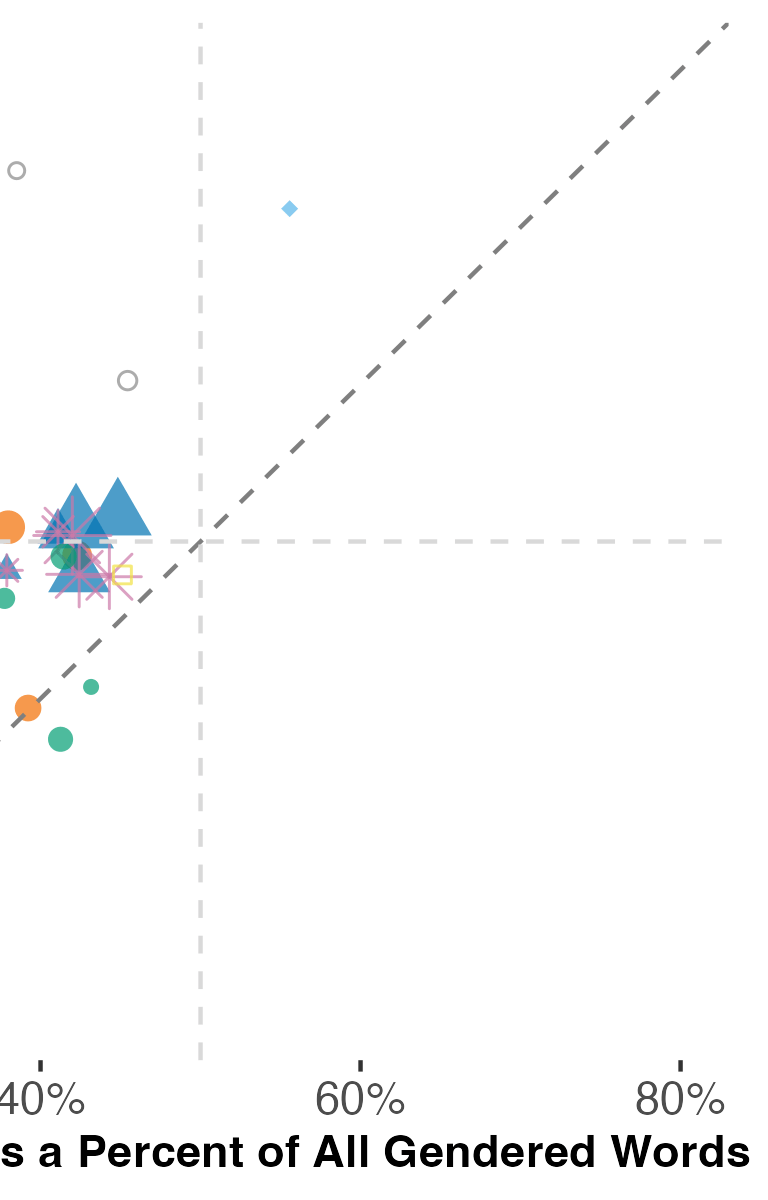

Moving from skin color to race, we also find that in both collections, Black and Latino people have been underrepresented in these books, relative to their share of the U.S. population, corroborating prior work on the representation of race in smaller subsets of these collections of books. Our analysis of gender shows that, again in both collections, females are also less likely than males to be present in these books, despite equal population shares. Digging deeper, we compare how often females appear in images, as compared to in text. We find that females are consistently more likely to be visualized (seen) in images than mentioned (read) in the text, which suggests more symbolic inclusion in pictures more than substantive inclusion in the actual story. Figure 3 below plots this result.

Figure 3. Female representation in images and text of children’s books

Note: This figure plots collection-by-decade average percentages of female representation in images (on the y-axis) and female representation in text (on the x-axis). This enables a comparison between the proportion of females represented in the images and the proportion of females represented in the text of the children’s books in our sample.

Source: Author’s calculations. See paper for additional details.

Over time, however, the patterns show signs of change. As time progresses, both collections of books include more characters with darker skin tones. Further, over the period we study, the representation of both race and gender trend closer to equality, though neither ever reach proportional representation, relative to the larger population.

Our paper then analyzes separate data on the checkouts of books in libraries and purchases of books by households to better understand what shapes who consumes different types of children’s books. We find that people tend to buy books that contain characters who share their gender and racial identities. Yet books centering many historically minoritized identities are either more scarce than other books, more expensive, or both. This suggests that greater provision of—and access to—books representing a more diverse range of identities than is currently available would fill a clear and desired need in the market. We also find that the content of books that people in a given area purchase are correlated with the political leanings of a community: in areas where progressive views are more common, people consume books with a more diverse range of identities represented than in areas where conservative views prevail.

Conclusion and implications

This research investigates who is represented; in other work, we also investigate how people are represented in children’s books. In these analyses, we show that the manner in which people are represented to children often reproduces societal norms and disparities. We see, for example, that females are more likely to be described relative to their appearance and roles in the family, while males are more likely to be described relative to their competence and roles in business. A century ago, we see a substantial gap between the sentiment, or overall positive feelings, associated with females and males—with males being shown in substantially more positive terms. Over time, however, this difference narrowed and is no longer detectable in books published today. We find similar disparities in the representation of race. For example, Black people, and Black women in particular, are more likely than white people to be mentioned in passages with more negative sentiment. While this gap, too, has lessened over time, in many contemporary stories we still find more negative sentiment associated with Black individuals than others.

Prior research has shown that the content of books can shape children’s beliefs, performance in school, and ultimately the adults they become. Our analysis shows that the representation of characters in books—and in award-winning, highly visible children’s books in particular—conveys important messages about how society values people by their race and gender. These messages trend towards equality over time, but even in many books published today, they still send the message that white people and males are the most visible and thus the most important members of society. This finding highlights some potential harms to children from recent political conflicts over critical race theory and the efforts to ban certain books that have sprung from these conflicts. It also underscores the important work that librarians, teachers, and parents play in building out school and home libraries with content showing a diversity of representation. These efforts can help ensure we teach children that all people can inhabit the many rich potential futures that await them.

Commentary

What award-winning children’s books teach children about race and gender

June 2, 2023