With the fall semester two or three months underway in most states in the U.S., everyone is wondering: After the COVID-19 pandemic forced a nationwide school shutdown, are schools doing better now than they were in the spring? With virtually all schools across the nation closed by April and scrambling to transition to online learning with no preparation, the spring was “not pretty.”

An initial glimpse at recent survey data suggests, yes, schools are doing better! The Understanding America Study (UAS), a nationally representative panel of households, has been posing questions to the same families over time since the spring. The UAS—funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the National Science Foundation, and run by the USC Dornsife Center for Economic and Social Research—includes 1,335 households with at least one pre-K-12th grade child as of our most recent wave. Overall, the UAS finds that parents’ ratings about the quality of their children’s education are improving, and fewer parents are expressing concern about their child’s academics.

But drawing conclusions from these results misses some important details. In the spring, all families were experiencing the same educational context—schools were closed and students were, at least in principle, learning from home. Distance learning was new to just about everyone, everywhere. Schools across the nation were fighting the same battle, trying to educate and provide services like meals to students with school buildings closed. But now, an important difference exists underlying respondents’ answers: Some are back to in-person learning every day, others are exclusively learning from home, while others are in a hybrid setting—switching back and forth between learning from home and school.

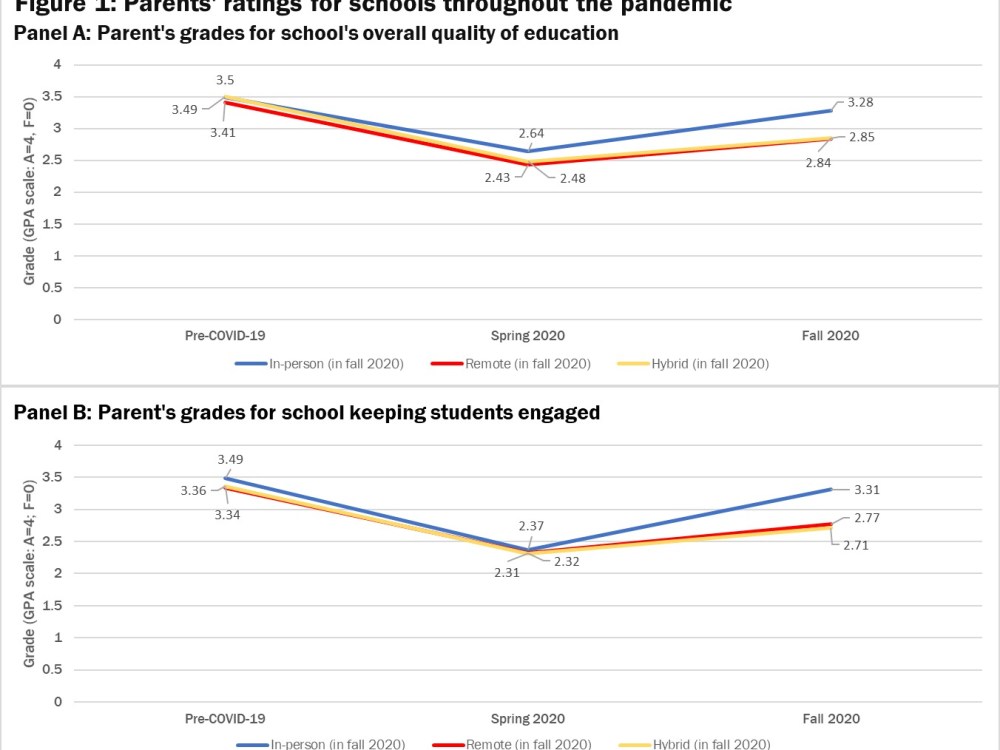

When we look at survey responses based on the context of the learner, reality comes into sharper focus. And while some things may be improving, it turns out that nearly all of the improvement is for students who are going to school in person. Echoing recent findings from Pew, we find that students still at home, or even those in a hybrid schedule, are hardly better off than they were in the spring.

Quality of education

We asked parents to rate their child’s school on a familiar A-F grading scale across various important dimensions, treating their responses like a regular grade point average (A = 4, B = 3, C = 2, D = 1, F = 0). We asked them to assign a grade to how their school was doing now (in October 2020), how they did in the spring during school shutdowns, and how they did before COVID entered our lives. When we look at results overall, we see an optimistic picture: The quality of education has improved since spring shutdowns, students are more engaged now in the fall than they were in the spring, and students’ relationships with teachers are better now than in the spring. On all questions we asked, parent responses reflected a “partial recovery” of sorts—not all the way back to pre-COVID-19 levels, but improved since the spring.

| Dimension | 2020 Pre-COVID-19 | Spring 2020 (Initial school closures) | Fall 2020 |

| Quality of education | 3.44 | 2.50 | 2.97 |

| Quality of feedback from teacher(s) | 3.36 | 2.67 | 3.05 |

| Keeping student engaged | 3.38 | 2.33 | 2.92 |

| Students’ relationship(s) with teacher(s) | 3.48 | 2.77 | 3.07 |

| Quality of instruction in science | 3.37 | 2.42 | 2.95 |

| Quality of instruction in math | 3.35 | 2.47 | 2.97 |

| Quality of instruction in Language Arts | 3.44 | 2.50 | 3.02 |

However, this result is misleading. When responses are disaggregated by how the child is attending school, we see a different picture. The “recovery” in ratings is driven by families where children have returned to school in person. In fact, among those whose children are still remote, parent grades for the overall quality of education and for keeping students engaged are much closer to where they were during spring shutdowns. Notably, families with students attending school in a hybrid model tend to respond similarly to parents whose students are exclusively remote.

Similar misleading “recovery” patterns emerge when we look at parent concerns. Unlike the grading questions, these questions were asked contemporaneously in the summer and again in the fall. Overall, concern about the quality of education the school will deliver seems to have improved over time, from 46% of parents being concerned or very concerned over the summer compared to 34% in the fall. But again, the seeming recovery is driven by in-person school attendance. In reality, concern about the quality of education the school will deliver dropped substantially among families where students are now attending in-person, down from 40% in the spring to 21% in the fall, but the drop was smaller for remote or hybrid families.

When it comes to non-academic concerns, overall parents continue to be concerned about children’s social and emotional well-being, with a bit more than one-third reporting concern both over the summer and in the fall. But, this overall pattern masks an important truth: Almost half of parents whose children are remote are concerned about their child’s social or emotional well-being, compared to approximately one-quarter of parents whose children are in-person, with parents of hybrid children falling in-between. In other words, concern about social-emotional health has become more common for remote families, while it is becoming less common for in-person families.

As the 2020-21 school year presses on, we must be careful not to over-interpret insights from surveys, including nationally representative polls, when they aggregate responses across families experiencing different realities. While students returning to in-person learning are benefiting from important social-emotional connections, relationships with teachers and peers, and potentially improved academic experiences, some form of remote instruction is here to stay for the remainder of the 2020-21 school year. We must continue to monitor the quality of remote instruction, as well as the physical, social, emotional, and academic needs of our nation’s children.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 2037179. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Commentary

Surveys show things are better for students than they were in the spring—or do they?

November 18, 2020