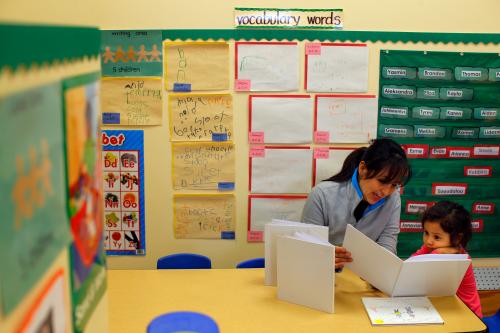

Pre-kindergarten education has long generated attention from policymakers, parents, and educators seeking to create a foundation for the academic success of American children. States have taken note: In 2015, 42 states and the District of Columbia allocated $6.2 billion in state funding to pre-K programs.

While investments in preschool are up, the research on its effectiveness and long-term benefits shows no clear consensus. Two rigorous recent studies challenged widely held beliefs on the benefits of pre-K education, and the swearing-in of a new secretary of education has reignited debates over the funding and future of early childhood education in the U.S.

Brookings experts and their peers have explored these studies, conducted their own pre-K research, and provided policy recommendations for how they think early childhood education should be addressed under the new administration. A sample of their work—and their ongoing debate over the effectiveness and future of pre-K—is highlighted below.

STUDIES CHALLENGE ASSUMPTIONS ON THE BENEFITS OF PRE-K

In order to assess the short- and long-term effects of pre-K on student achievement, two recent studies followed and measured the academic progress of children through third grade. The first and perhaps most widely cited report, the Tennessee Voluntary Pre-K study, found that any early gains from pre-K education were short-lived. The study’s control group of children who did not participate in pre-K actually surpassed the pre-K group in achievement by second and third grade.

Addressing why the study showed a negative impact on the sample group rather than a fade-out effect, Richard Reeves, co-director of the Center on Children and Families, and Edward Rodrigue pointed to the lack of consensus about what pre-K actually is. They noted that Tennessee’s “rigid, academic approach” could be responsible for the children in the pre-K group disengaging from school in future years.

Education experts Andres Bustamante, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, Deborah Lowe Vandell, and Roberta Michnick Golinkoff also evaluated the study in a Brookings blog post that outlined reasons why they believe Education Secretary Betsy DeVos should embrace early childhood education. The authors highlighted flaws in the study’s design and offered education policy recommendations for the new administration. “With respect to the Tennessee study,” the wrote:

Observations revealed that 85 percent of classrooms scored lower than “good quality” on the Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale (ECERS-R), a widely used measure of quality. Indeed, the Tennessee researchers admit that during scale up of the program “little infrastructure for supporting professional development with teachers or overseeing what they are doing.” It should come as no surprise that we will see muted outcomes when quality is not high. Findings like these underscore why access will not compensate for quality as we set standards for preschool settings.

The “secret to success,” said these authors, is to follow the clear pattern of results from a number of other pre-K studies. These data, they wrote, provide the basis of their key policy recommendations: support programs that start early (from infancy to 3 years old), support parents, and are of the highest quality.

Dale Farran and Mark Lipsey disputed Bustamante, Hirsh-Pasek, Vandell, and Golinkoff’s recommendations, writing that scaled-up pre-K programs are linked to short-term success but long-term fade-out. Farran and Lipsey suggested that a “more complex vision of ‘high quality’ is needed—along with a plan for achieving it.”

WHAT WE KNOW: CONSENSUS STATEMENTS ON THE CURRENT STATE OF KNOWLEDGE ON PRE-K

A task force comprised of experts from Brookings and Duke University compiled six consensus statements from a wide range of research on what is known about the effects of pre-K, and what is missing from the current research. Here’s what they identified:

- Economically disadvantaged and dual-language learners often experience greater improvement from these programs than their more advantaged peers.

- Not all pre-K programs successfully support early learning. The most effective programs offer “rich interactions” between peers and teachers through effective curricula, professional development and coaching for teachers, and organized and engaging classrooms.

- The odds of beneficial pre-K impacts are greatest when children’s experiences prior to, during, and after pre-K are collectively considered as part of the equation for success.

- Convincing evidence shows that children attending a diverse array of state and school district pre-K programs are more ready for school at the end of their pre-K year than children who do not attend pre-K.

- Convincing evidence on the longer-term impacts of contemporary scaled-up pre-K programs on academic outcomes and school progress is sparse, precluding broad conclusions.

- Ongoing innovation and evaluation are needed during and after pre-K to ensure continued improvement in creating and sustaining children’s learning gains.

Watch these experts and others discuss and debate these consensus statements during a recent Brookings event.

WHAT WE DON’T KNOW ABOUT PRE-K EDUCATION

Brookings expert Russ Whitehurst argues that much of the evidence on pre-K is “often weak, misleading, or irrelevant.” Whitehurst writes that current programs and the methodology for measuring the success of these programs need to be re-examined. However, he adds that investment in early education should continue, and increase, despite that uncertainty.

Go forward with promising ideas with a public acknowledgement of uncertainty and an approach designed to learn from error. Don’t place big and irrevocable bets on conclusions and recommendations that are far out in front of what a careful reading of the underlying evidence can support. Very few policy prescriptions are slam-dunks, even those that seem to have good research behind them. In the early education and care of children, just as in the rest of social policy, we need to be a learning society, prepared to try new approaches to address pressing problems and to learn systematically from trial and error in their implementation.

Brookings Senior Fellow Isabel Sawhill agrees that the current research on the effectiveness of pre-K is inadequate. Sawhill says it will take a generation to get answers to this kind of research, and by that time, the results may not be relevant to the contemporary environment. Despite that, she says, “The evidence will never be air-tight. But once one adds it all up, investing in high quality pre-K looks like a good bet to me.”

WHAT’S NEXT?

Policymakers, social scientists, and the public all have a stake in the young minds of America. While current research may lack conclusive evidence of pre-K’s impact, what is clear from the research and analysis of Brookings experts and others is the need for additional examination to determine the interventions needed to support the growth and development of the next generation.

Commentary

Does pre-K work? Brookings experts weigh in on America’s early childhood education debate

May 26, 2017