In my recent blog post, I examined the financial pledges China made at the 2018 Beijing Summit of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) and the evolving Chinese economic priorities these commitments represent. Beyond the specific financial commitments, the rest of the eight actions meet the traditional checklist on infrastructure, agriculture and industrialization, and trade facilitation, and continue to expand on China’s interests in green development, health care, and peace and security issues.

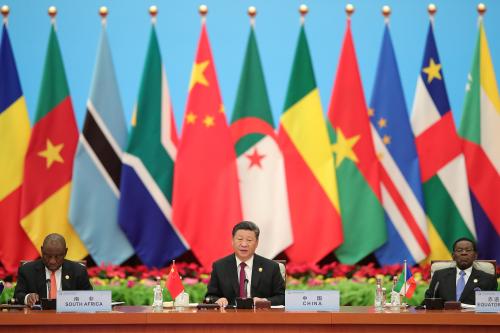

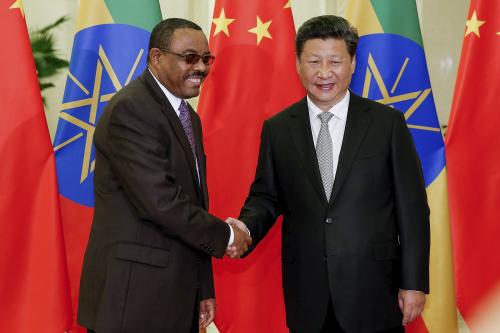

As a political event, the FOCAC Summit usually reflects China’s current priorities in foreign strategy. The Beijing Summit was no exception. In the eight days during and around the summit, Chinese President Xi Jinping met with every leader from the 53 African countries present at the event, emphasizing a Sino-Africa Community of Common Destiny. Judging from the statements, the summit advanced two political messages. Externally, China is making serious efforts to consolidate African countries’ support of China’s international agenda, especially in light of the Trump administration’s China and trade policies. Internally, between China and Africa, China is upping its game on Africa’s capacity building, a phrase currently spearheaded by China’s soft power campaign and effort to promote the Chinese model of political and economic development in developing countries.

The 2018 FOCAC Summit occurred at a time when Chinese foreign policy has encountered major obstacles. On the one hand, the U.S.-China trade war has raised questions, domestically and externally, about China’s ability to sustain hostilities with the U.S. On the other hand, China’s own Belt and Road Initiative, five years after its launch, has run into serious questions about China’s expansionist intention as well as financial and security concerns from the recipient countries.

At this critical juncture, Africa could provide the needed moral, rhetorical, and political support of China’s benevolent intention and global leadership. The Sino-Africa Community of Common Destiny approach is based on the closely connected fate of China and Africa as emerging markets and developing countries. Such an alliance could challenge the global north led by the U.S., eventually supporting a more balanced international power equilibrium. China and the 53 African countries agreed to “jointly defend the core national interests of each other as well as the interests of developing countries as a whole.” The two sides made a commitment to push for a new model of international relations that is based on mutual respect, fairness, justice, cooperation, and win-win solutions. The “new model of international relations,” or the “democratization of the international relations,” has long been the focus of China’s effort to reform the international system to give China and its allied developing countries a bigger voice and more power. By tying African countries into that narrative, China is consolidating the foundation for its bid to shape a new international order.

The political messages to the U.S. from the FOCAC Summit is clear through the joint statement: Without naming names, China and Africa both opposed protectionism and unilateralism, pledging their support for an open world economy and the multilateral trade system. Although China has tried to rally support with developed countries such as those in Europe, Asia, and North America for a coalition against the Trump administration’s trade policy, such efforts have not been particularly successful given those countries’ similar grievance over China’s trade practices. Now with Africa, China’s implicit calling for a coalition finally meets some positive support.

To push back on the recent criticisms of China’s relationship with Africa, President Xi particularly pointed to the “five no” approach in China’s Africa policy: “No interference in the development paths of individual countries; no interference in their internal affairs; no imposition of China’s will; no attachment of political strings regarding assistance; and no seeking of selfish political gains in investment and financing cooperation.” Such a claim sounds positive but deserves reflection rather than being taken literally. China’s traditional approach toward Africa on political issues is not coercion oriented but remuneration oriented. Africa’s impact on China’s core national interests is minimal; therefore, it does not justify a coercive approach. Furthermore, China has learned the lesson that the political favors it needs from Africa, such as the support of China’s international agenda, can be achieved through tacit economic remuneration. This implicit but transactional nature of the relationship has made it easy for grandstanding.

One major shift in China’s policy from the FOCAC Beijing Summit lies in the expansion of China’s capacity building programs in Africa, both qualitatively and quantitatively. In the 2015 FOCAC commitment, China divided government scholarships and training programs into “cultural cooperation” and “poverty alleviation cooperation.” However, this time around, China specifically raised the banner of capacity building actions. China stated that the goal is to strengthen the exchanges of development experiences and to pursue cooperation in the field of socio-economic development planning. However, in the past decade or so, China’s capacity building programs, especially training programs for African officials and young leaders, have morphed into a systematic campaign to promote China’s development achievements, development models, and bilateral cooperation. In a Western concept, the Chinese capacity building borders the export of Chinese ideology, albeit in a more implicit and indirect form. However, in this case, China’s power does not lie in its imposition, but in its inspiration.

In this sense, what is shocking is the quantitative enhancement of China’s capacity building training programs in Africa. In the 2015 FOCAC commitment, China committed to a total of 2,000 educational degree program opportunities, 30,000 government fellowships, visits by 200 African scholars, and training for 500 African youths and 1,000 media personnel. However, this year, the number of government fellowships jumped from 30,000 to 50,000, in addition to the 1,000 African leaders that China will train. Demonstrating China’s keen interests in shaping the next generation of African leaders, China quadrupled the number of African youths to be invited to China for exchanges to 2,000. All of these are impressive, but none are as jaw-dropping as the number of capacity building and training opportunities China has agreed to provide: 50,000 training opportunities to African countries, including government officials, opinion leaders, scholars, journalists, and technical experts. These are essentially the African political, economic, and social elites and opinion leaders that will shape the future of the continent and its relations with China.

If there is any political takeaway from the 2018 FOCAC Beijing Summit, it is that China’s bid for Africa has heightened. More than ever before, Africa is emphasized as the “foundation of the foundations of China’s foreign policy” to rally support of developing countries. Such coalition building is not just done through economic reward, but increasingly through the indirect, implicit, and sophisticated campaigns to win the hearts and minds of today and tomorrow’s African elites.

Commentary

The political significance of China’s latest commitments to Africa

September 12, 2018