Below is a viewpoint from Chapter 6 of the Foresight Africa 2018 report, which explores six overarching themes that provide opportunities for Africa to overcome its obstacles and spur inclusive growth. Read the full chapter on the changing nature of Africa’s external relationships here.

There has generally been continuity in United States policy toward Africa over the last three administrations, and there is potential for that continuity to be sustained under the Trump administration. However, the lack of key appointments and a growing emphasis on security and counterterrorism so far define the Trump administration’s approach to the continent. Key Africa policy positions—most notably the assistant secretary of state for African affairs—have yet to be filled by a Senate-confirmed appointee, and ambassadorships across the continent, including in pivotal countries such as South Africa, Tanzania, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, remain unoccupied. These vacancies make designing and executing a comprehensive strategy for a diverse, fast-changing continent—a tall task at the best of times—virtually impossible.

Developments in Africa will not wait for U.S. policy to catch-up, and 2018 promises to be an eventful year. Challenges concerning violence, extremism, governance, and human rights will persist, but at the same time the enormous opportunities in Africa, especially in trade and investment, will continue to expand. In past administrations, the United States has engaged Africa through an array of initiatives, such as the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), the Millennium Challenge Corporation, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, Power Africa, the Young African Leaders Initiative, and the Security Governance Initiative. A year into the Trump administration, which included two days of meetings in November with the chair of the African Union and 37 foreign ministers from the continent, the U.S. approach to the region is still unclear.

Concerning peace and stability challenges, the civil war in South Sudan has displaced more than a third of the population of approximately 12 million. The United States has traditionally played a leadership role with South Sudan, but the Trump administration, in part through the closure of the office of special envoy of Sudan and South Sudan, has demonstrated that it does not embrace these historical obligations. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, President Joseph Kabila’s strategy of glissement—slow-rolling preparations for elections now scheduled for December 2018, in which he is barred from running due to term limits—threatens to throw the country and, possibly the region, into political chaos. No meaningful actions or pressures have been taken against the regime despite a visit by U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley, the apparent leader of U.S. policy on these issues.

A year into the Trump administration…the U.S. approach to the region is still unclear.

Violent extremism persists in several African countries with al-Shabaab in East Africa and Boko Haram in the Lake Chad basin. In addition, the multitude of extremist groups operating in the Sahel are likely to garner increasing U.S. attention in 2018 following the death of four American soldiers in Niger in October. The growing U.S. military footprint in Africa, highlighted by an estimated 6,000 troops in the region, the attack in Niger, and a stepped-up response to ISIS militants in northeastern Somalia could overshadow other priorities, such as good governance and human rights, especially given the many diplomatic vacancies and reduction in the State Department budget.

Nevertheless, advancing democratic governance should continue to be a top priority for the Trump administration. The greatest potential for democratic progress in 2018 may be found in Zimbabwe, where President Robert Mugabe was dramatically removed from office late in 2017. The United States will face policy decisions concerning how to engage new President Emmerson Mnangagwa (who is closely linked with human rights abuses over decades), whether to remove long-standing sanctions, and how to support elections scheduled for the summer of 2018. Even as Mugabe departs, some of Africa’s long-serving leaders, including Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni (a U.S. ally in counterterrorism) and Burundian President Pierre Nkurunziza, are maneuvering to remain in office, which will test the United States’ tolerance for leaders to remove term limits and rule indefinitely. In Kenya, another U.S. counterterrorism ally, the political uncertainties resulting from tumultuous 2017 elections may limit democratic and economic progress, and again will test the United States’ foreign policy position on democratic governance.

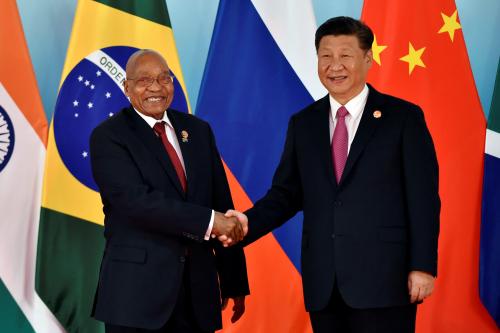

Finally, trade and investment appears to be a second-tier priority for the Trump administration in Africa—even though last year U.S. direct investment in the region grew to $57.5 billion, the highest level ever, according to the State Department. In addition, United States Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer’s showed leadership at the AGOA forum in Togo in August. The continuation of the Obama-era Presidential Advisory Committee on Doing Business in Africa housed in the Commerce Department is a positive signal. Commercial opportunities on the continent, especially in infrastructure, power, mobile banking, financial services, and consumer products, will continue to expand, but it remains to be seen whether the administration has the interest or personnel to take advantage of them. There are no indications that the administration plans to transition any time soon to a more reciprocal trade agreement following AGOA to support U.S. exports and investments in the face of the growing dominance throughout Africa of European and Chinese companies.

Commentary

Foresight Africa viewpoint – The US and Africa in 2018

January 30, 2018