Both the United States and China have considerable economic interests at stake in Africa that require a peaceful and stable domestic environment—offering incentives for bilateral cooperation on African security issues. Certain non-traditional security threats in Africa, such as terrorism, piracy in the Gulf of Aden, and transnational crimes affect the national interests of both countries. The most direct impact is when these activities directly targets Chinese or American entities, while the instability they generate exacerbates the overall political vulnerability of African states and damages their economic environment. Both U.S. and China see an inherent responsibility to African peace and security issues as great powers. However, U.S.-China cooperation is taking place through multilateral platforms, such as through United Nations peacekeeping and counter-piracy mechanisms, while there remains great potential for more bilateral cooperation on African security issues.

Multilateral collaboration is the norm for U.S.-China security collaboration in Africa

U.N. peacekeeping might be the most concrete area where the U.S. and China work together on African peace and conflict issues. The U.S. currently remains the largest financial contributor to U.N. peacekeeping, amounting to 28 percent of the increasingly expensive $8.2 billion annual budget. In comparison, China is only the sixth-largest financial contributor with 6.64 percent of the total budget of the U.N. peacekeeping mission, but it is also the largest contributor of peacekeepers among the five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council. The total number of Chinese peacekeepers (2,262) is almost twice as large as the other four countries’ contributions combined. Since 2013, China has provided security forces for the first time in United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), a trend that continued in 2014 when China started to deploy combat troops to the United Nations Mission in the Republic of South Sudan (UNMISS).

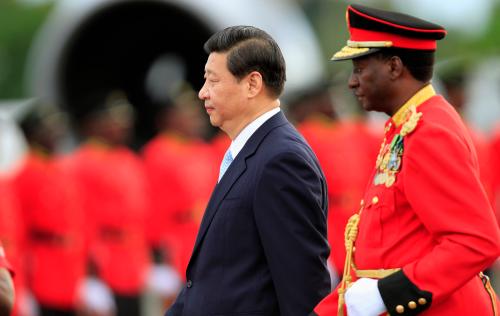

Most U.S.-China cooperation on African security affairs therefore manifests itself in the joint support of the U.N. peacekeeping missions in Africa. The two countries do work with each other in strengthening the U.N.’s capability in this regard. Last September, Chinese President Xi Jinping agreed with President Obama that both countries would increase their “robust” peacekeeping commitments during his state visit to the U.S. Responding to such a call by Obama, Xi announced that China would join the new U.N. peacekeeping capability readiness system, and would lead in setting up a permanent peacekeeping police squad and building a peacekeeping standby force of 8,000 troops.

Besides the cooperative political commitment on the top level, the two countries recognize the need to deepen their partnership on peace operations and learn from each other’s experiences on the working level. For example, this past March an eight-member U.S. military observer delegation visited the UNMISS Chinese peacekeeping infantry battalion in South Sudan. It remains a bit underwhelming that the visit did not go beyond a courtesy call, nevertheless, communications and information exchange indeed exist between the two.

The U.S. and China have held bilateral counter-piracy exercises in the Gulf of Aden and the Horn of Africa aimed to promote partnership, strength, and presence.

Another key area of security cooperation between the U.S. and China in Africa on the multilateral level is in the field of counter-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden. Under the authorization and mandate of U.N. Security Council resolutions, many countries, including China and the U.S. have deployed forces in the region to counter the rising threat of piracy. For instance, the Chinese naval presence focuses on escort missions of Chinese and foreign ships in the maritime area. The U.S. and China have held bilateral counter-piracy exercises in the Gulf of Aden and the Horn of Africa aimed to promote partnership, strength, and presence. For example, the exercise in 2014 included combined visit, board, search and seizure operations, communication exchanges, and various other aspects of naval actions. Beyond this exercise, both the U.S. and China also participate in multilateral mechanisms for information sharing there.

Counter-piracy cooperation has demonstrated—through their committed resources and willingness to work together when the stakes are high and the threat is dire—that further cooperation in broader areas on safeguarding freedom of navigation and non-traditional, lethal security threats in other parts of Africa is possible.

The scope of such bilateral collaboration under a multilateral framework is expanding. Nevertheless, certain obstacles will hinder the pace and depth of such cooperation. Using the escort missions in the Gulf of Aden as an example, China prefers unilateral escort missions to multilateral cooperative ones for fear of being enmeshed in the rules, systems, and agendas of Western countries. Thus, the nature of the Chinese escort missions has remained largely defensive and protective; China remains very reluctant to actively pursue pirates. This tendency is closely associated with China’s defensive overseas military strategy and is unlikely to change in the near future.

Bilateral cooperation between Washington and Beijing has room to grow

So far, on the national level, the most official and consistent channel of communications between the two countries is the U.S.-China consultation on African affairs. As of 2016, the U.S. State Department and the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs have held seven rounds of such bilateral consultations. The vice-ministerial level bilateral consultation takes place every two years (on average), with its venue alternating between Beijing and Washington. The consultation is jointly chaired by the top officials in charge of the African policies of both countries, the Chinese vice/assistant minister, and the U.S. assistant secretary of state for Africa, respectively.

Judging from the Chinese official press releases[i] on these consultations, before 2011, much of the conversation focused on learning each other’s priorities in their respective African policies and the new issues in their cooperation with Africa. Such wording has disappeared since the fifth round, of consultation in 2011, which probably illustrates an improved knowledge in both Beijing and Washington about each other’s Africa policies The same is true on the “positive comments by the U.S. on the contribution China has made to African development in recent years.” One consistent theme of the consultations has been “in-depth exchanges of opinions” on the situation in Africa and key regional issues. Based on these exchanges, the U.S. and China are committed to strengthening communications and coordination in order to help Africa achieve peace, stability, and development. However, it seems that on the bilateral level, rhetoric exceeds actions.

Despite U.S. keen interest in fighting terrorism in Africa, such an interest it yet to be echoed by Beijing.

This is particularly true in terms of the lack of concrete actions on the counterterrorism cooperation between U.S. and China in Africa. Although terrorism threats are identified as a key priority in China’s national security strategy, such concerns are focused on domestic terrorist activities. Foreign terrorism is only treated with a heightened level of attention when it targets China or assists organizations or individuals that target China. In this sense, despite U.S. keen interest in fighting terrorism in Africa, such an interest it yet to be echoed by Beijing.

The discussion between the U.S. and China on counter-piracy in Africa seems to be gaining momentum recently, at least on the track-II level. On July 27, 2016, the human rights-focused nonprofit Carter Center convened its third Africa-China-United States Consultation for Peace and Development in Lome, Togo. The consultation this year has focused on maritime piracy as well as peace-related issues in the Sahel region. China’s former special representative for African Affairs, Zhong Jianhua, and the former U.S. Special Envoy for Sudan and South Sudan, Princeton Lyman, co-chaired the Track-II dialogue. This might indeed be the first trilateral dialogue on maritime security between the U.S., China, and Africa.

Given the challenges and stakes at hand in African security affairs, people would expect more in-depth dialogues and real actions between U.S. and China on the issue. While there are more actions on the multilateral level currently, bilateral cooperation still has large potential. Among other heated security issues between Beijing and Washington, Africa is perhaps the most under-explored.

Note: For a more detailed discussion on China’s security interest in Africa, please see Brookings policy report, “Africa in China’s Foreign Policy.”

For previous discussion on the constraints to U.S.-China cooperation in Africa, please see Brookings blog piece, “The Limits of US-China Cooperation in Africa.”

For previous discussion on U.S.-China cooperation in African terrorism, please see Brookings blog piece, “China and the Rising Terrorism in Africa: Time for U.S.-China Cooperation?”

[i] For the official press release from the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs:

The Third Sino-US Consultation on African Affairs, 2008; The Fourth Sino-US Consultation on African Affairs, 2010; The Fifth Sino-US Consultation on African Affairs, 2011, The Sixth Sino-US Consultation on African Affairs, 2014; and The Seventh Sino-US Consultation on African Affairs, 2016.

Commentary

US-China cooperation on African security

November 1, 2016