December 20 is Election Day in Madagascar. Neither the current president, Andry Rajoelina, nor the ousted president, Marc Ravalomanana, is on the ballot as they were both barred from running as a precondition to the results being internationally recognized. However, the key candidates in the run-off presidential election, which will be coupled with the legislative elections, are perceived to be their proxy candidates. As a result, many people have mixed feelings about the potential for these elections to end the political crisis that has lasted for almost five years. Skeptics are comparing it to a choice between the plague and cholera. Others consider the election a battle between two gangs of bandits, only behaving in their own selfish interests. On the other hand, we are optimistic and would like to believe that both camps truly care about the welfare of their fellow citizens and are driven by noble, patriotic ambitions.

We do, however, find the bandit analogy interesting, especially in terms of explaining Madagascar’s recent economic trends. Assuming that the Ravalomanana regime (2003-2008) and the Rajoelina one (2009-2013) have, in fact, acted like gangs of bandits (which may or may not be true), it should be pointed out that they did so in very different ways. Ravalomanana and his cohort acted like a “stationary gangs of bandits,” while the others like a “roving hoard of bandits.” That nuance is reflected in their social and economic performances during their respective tenures. Of course, other factors may have affected those performances such as technical policymaking skills, international sanctions or the suspension of official development assistance. We are merely exploring one potential piece of the complicated puzzle.

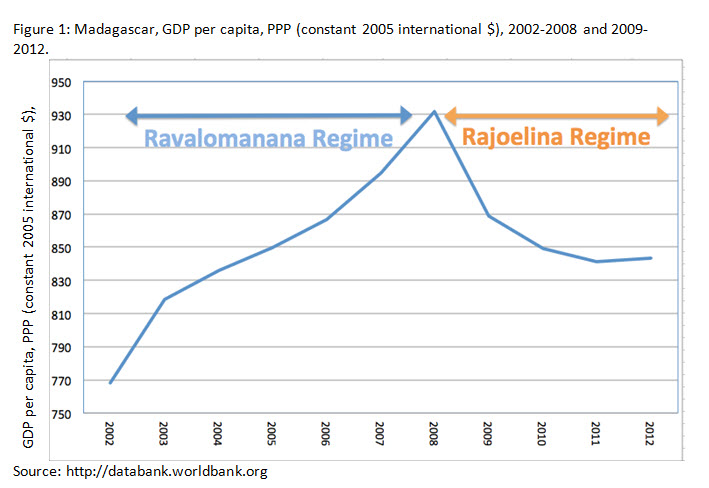

The concept (borrowed and adapted from the late economist Mancur Olson) is very simple and intuitive. “Stationary bandits”—politicians that expect to stay in power for a relatively long period of time—have the incentive to pursue policies aimed at generating robust economic success, since they plan to remain in power long enough to take a share of it. They will take (or steal) from the population, but not too much, since they realize that the wealthier their victims are, the better off they will be. They may even re-invest some of their loot into the local economy. This type of leader has an interest in providing peaceful order, protected property rights and other public goods that increase productivity and competitiveness—though for purely selfish reasons. We would then expect to see some economic growth (albeit not necessarily sustained) from this type of regime, as shown in Figure 1 from 2003-2008.

In contrast, “roving bandits”—politicians that are not certain about how long they will be in power, or whether they will be governing temporarily or during a transitory period—are likely to have only predatory incentives to steal (and destroy) as much as they can, and as fast as they can, while they can. This systematic plunder destroys any incentive to invest and produce, leaving very little for either the population, or even the bandits, in the long run. The roving bandit, par excellence, will take (or steal) everything from the population, extract any economic rents he can capture (e.g., in the mining, timber and other extractive sectors) and then move on with his loot. No economic growth is expected from this type of regime, as seen in Figure 1 in 2008 and onward. Instead, it is characterized by very rapid wealth accumulation by very few people.

It is possible that, if the roving bandit gains enough strength to legitimately control the country (say, by winning the election), his incentives may change. He may be tempted to stick around and become a stationary bandit. He will then find it in his interest to ensure that the country is as successful as possible by providing public goods that benefit the economy, which, in the medium run, will enhance his share of the prosperity.

The move from a roving bandit regime to a stationary regime may be welcome but it is not enough to bring sustained prosperity. To be sure, we believe that bandit regimes are not likely to yield sustainable development in the long run. Stationary bandits may be able to generate economic growth in the medium term, but such growth will be non-inclusive and unfair—a key ingredient of the Madagascar cycle. Sooner or later, people are going to start demanding real political and democratic reforms, either on the streets or through elections. What the Malagasy people need and want are real statesmen (or stateswomen) and not bandits. We hope that the winner of the election will be able to rise to the challenge.

Commentary

The Bandits of Madagascar

December 19, 2013