Millions of young Americans face an obstacle course after high school as they transition into adulthood. The path to further education and good jobs can be hard to find and access. This is especially true for young people from low-income backgrounds or those whose parents don’t have college degrees.

We know that decreased upward economic mobility is a serious national problem. For example, groundbreaking research from Raj Chetty and his team found that economic mobility is becoming less likely: Almost 90% of children born in the 1940s grew up to earn more than their parents, but that figure is only 50% for children born in the 1980s.

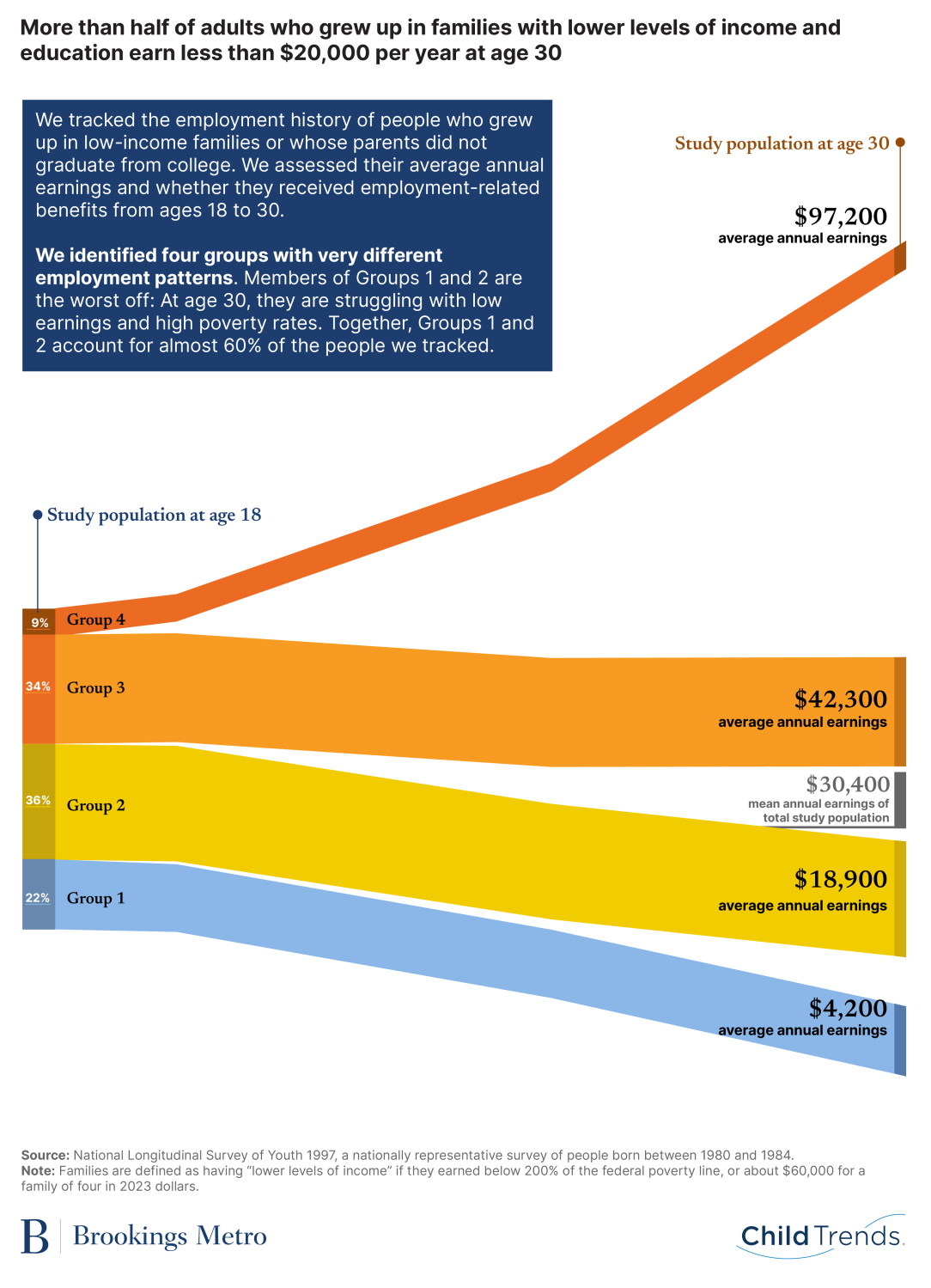

Brookings partnered with Child Trends to look more closely at the factors shaping upward mobility during a formative period in people’s lives: their teens to age 30. We wanted to get a fuller picture of whether people from families with lower levels of education and income find steady, decent-paying employment in adulthood. To do that, we identified teens whose parents did not graduate from college or who grew up in families earning below 200% of the federal poverty line (about $60,000 for a family of four in 2023 dollars). We followed this “study population” from age 18 to 30 to assess their average annual earnings and whether they received fringe benefits through their employer.

The findings were stark. Almost 60% of the study population experienced minimal earnings growth through their 20s and, at age 30, earned less than $20,000 per year.

Our full analysis is available here: Diverging employment pathways among young adults.

That income is not enough to live on, even for a single adult with no children. According to the MIT Living Wage Calculator, a single adult needs to earn upward of $30,000 per year to cover housing, food, transportation, medical care, and other necessities. People with children, of course, need to earn more to cover child care and other associated costs.

While it may not be surprising that people from modest backgrounds go on to earn modest wages, that is not what we are reporting here. The details and specificity matter: More than half of adults from modest backgrounds earn so little that they struggle to cover the basic costs of living.

This report describes the Brookings/Child Trends findings in more depth, provides more background on key educational and employment challenges, and recommends new approaches to prepare young people to succeed in adulthood.

Less than half of adults from modest family backgrounds achieve decent-paying employment at age 30

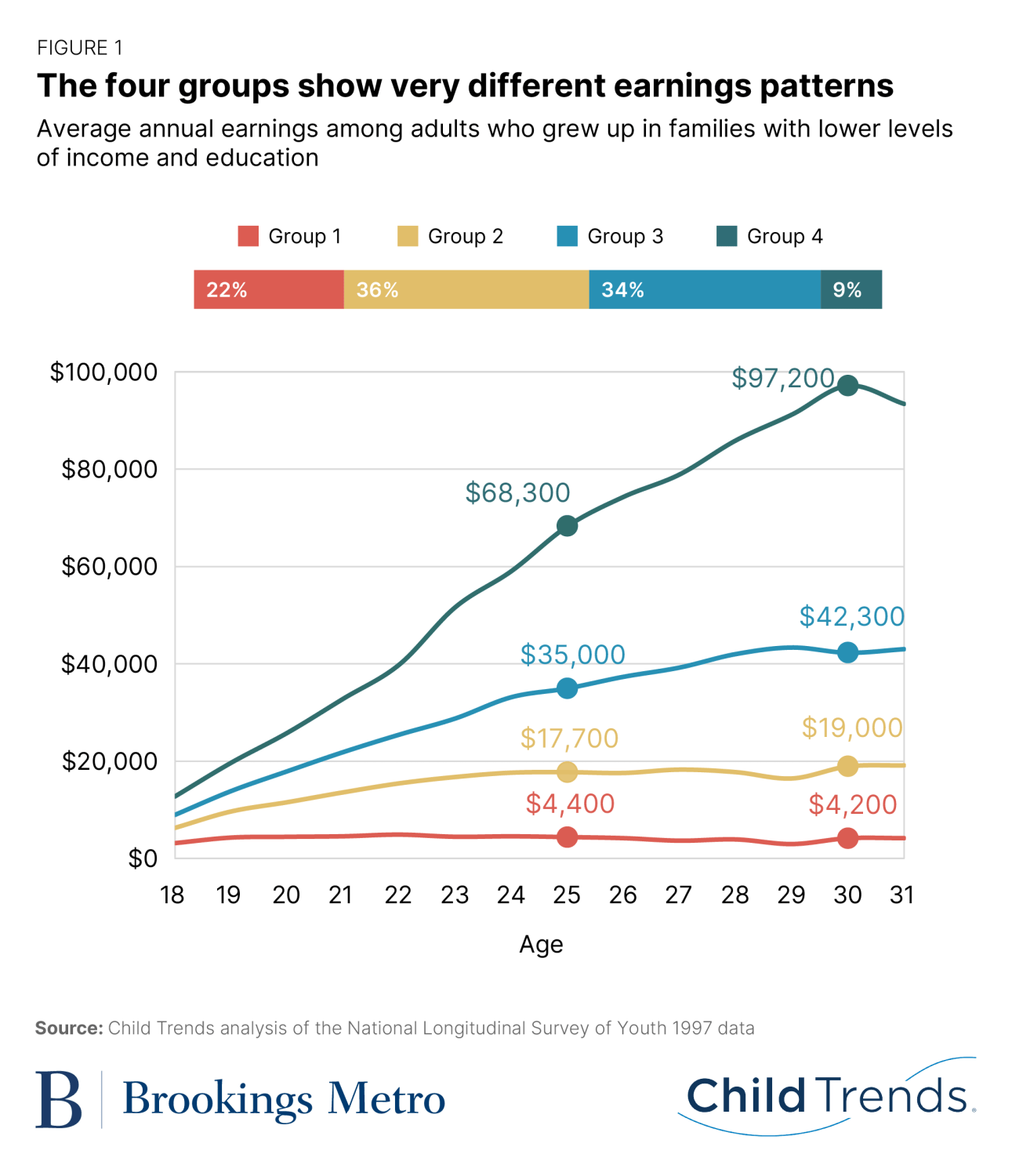

We used data from the 1997 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth to follow the employment histories of young people over time. We calculated the average annual wages of the study population and whether they received employment benefits (health insurance, paid leave, and retirement) from ages 18 to 30. Based on their earnings and benefits over the 12-year period, we clustered them into four groups. (For more information on our methods, please see here.)

Two of the groups experienced absolute economic hardship throughout their 20s and up to age 30. As shown in Figure 1, average annual earnings for individuals in Group 1 were $4,000 at age 30; $19,000 for Group 2; $42,000 for Group 3; and $97,000 for Group 4. The two lowest-earning groups are quite large: Group 1 accounts for 22% of the study population, or 2.5 million people, and Group 2 accounts for 36% of the study population, or 4.1 million people. Together, they account for nearly 60% of the study population.

The two lowest-earning groups are racially diverse, although Black people are disproportionately represented relative to their share of the study population. White people make up the largest share of Group 1 at 49%, followed by Black people (31%) and Latino or Hispanic people (15%). White people also make up the largest share of Group 2 (57%), followed by Black people (22%) and Latino or Hispanic people (17%). The two highest-earning groups are predominantly white: 63% of Group 3 is white, as is 71% of Group 4.

There are also gender disparities, likely influenced by occupational segregation and a greater tendency for women to perform family care work. The two highest-earning groups are predominantly male: Group 3 is 55% male and Group 4 is 78% male. By contrast, the two lowest-earning groups are majority-female.

Education and other factors shape employment pathways

We used multivariate analysis to identify the factors associated with membership in each group when numerous other influences are held constant. Not surprisingly, education plays a prominent role. Having a high school diploma or college degree reduced the probability of being in a low-earnings trajectory compared to people without a high school diploma.

Indeed, educational attainment in the two lowest-earning groups was very low: More than half (52%) of the lowest-earning group left high school without a diploma, as did nearly one-third (32%) of the second-lowest-earning group. And while some of those without diplomas went on to earn a GED, the GED was not associated with higher earnings, which aligns with research indicating labor market returns for GEDs are lower than returns for high school diplomas.

Other factors associated with belonging to a lower-earning group include work-limiting health conditions, holding a service sector job at age 25, prolonged unemployment, and incarceration. Factors associated with higher earnings include union membership and military service.

Given the array of factors shaping people’s employment trajectories, the responses must be wide-ranging as well. The rest of this piece focuses on education- and training-related reforms for improving earnings outcomes in the study population. Although education and training are not silver bullets, it is hard to imagine that we can create better futures for all young people without major changes in how we educate and prepare them for careers.

A high school diploma is critical to unlocking future possibilities—but not enough on its own

People with less than a high school diploma or only a high school diploma have a harder time finding work than those with higher levels of education—and the work they find doesn’t usually pay very well. Unemployment among adults with a high school diploma or less is often two to three times higher than for people with bachelor’s degrees. Meanwhile, when adjusted for inflation, median wages for workers with a high school diploma or less fell by 11% between 1979 and 2019, while they rose by 15% for workers with a bachelor’s degree or more. This one statistic explains a lot about how educational attainment is intertwined with inequality in America.

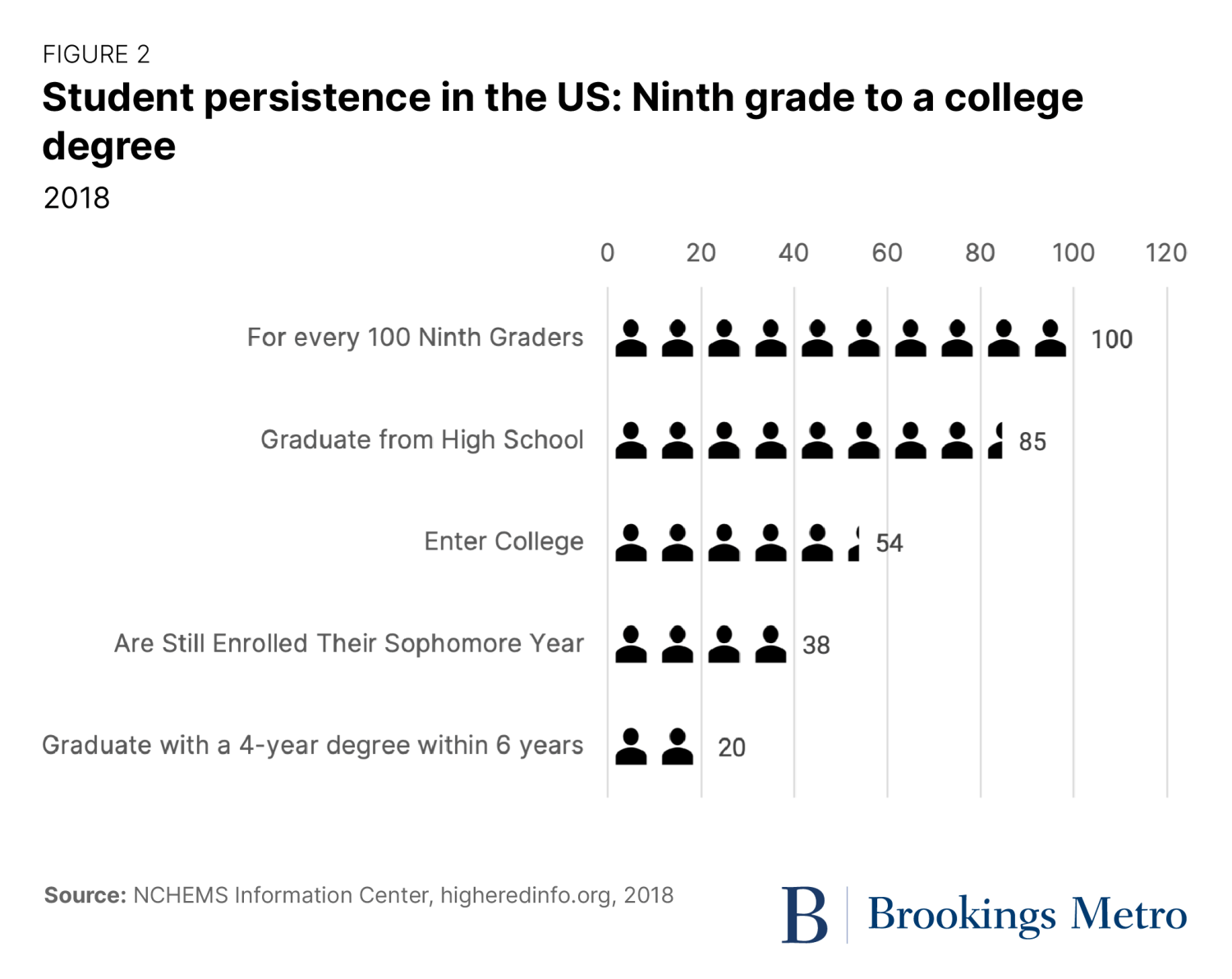

High school graduation rates have steadily increased over time, but they are still not at a level we should be satisfied with. More than half a million young people leave high school without a diploma every year, and this number compounds quickly over time. Over a five-year period, there will be 2.5 million more young people who should have high school diplomas but don’t. More than one in 10 students who enter ninth grade (13%) do not complete high school on time. Noncompletion rates are higher among students from low-income backgrounds, students with disabilities, and Black and Latino or Hispanic students.

But even those who graduate can face real difficulties in their transition to adulthood. Not everyone gets sufficient guidance, career information, or support from their family and schools about their options for pursuing higher education and/or employment. The landscape of postsecondary options is confusing, challenging to navigate, and financially out of reach for many.

The entire educational pipeline is leaky, as Figure 2 shows. Individuals drop out of the college track before high school graduation, after high school graduation, and after enrolling in college. For every 100 ninth graders, only 20 have earned a four-year degree six years after high school graduation. What options are there for the other 80?

This is not to imply that a college degree is the only answer. Currently, however, the academic college pathway is the most reliable gateway to economic opportunity. Those not on track to earn a traditional college degree will have a harder time finding their way to good jobs. Still, this serves neither students nor employers well. Too many students and families are saddled with debt as a result of rising college costs. And the employer practice of requiring college degrees for many positions—i.e., using the degree as a proxy for skills and competencies—is in fact counterproductive, as it artificially limits their recruitment pool and rules out good candidates.

We need a broader set of options to develop and recognize skills, as my colleague Annelies Goger has argued. These options should mix classroom and applied learning, and incorporate much stronger employer involvement. Apprenticeships and other forms of work-based learning provide valuable opportunities to learn and practice technical, academic, and interpersonal skills over a lifetime—not to mention the chance to build social and professional networks that can smooth the way to careers.

State and local leaders should dramatically increase their investments in educational and career pathways for young adults

The findings highlight the urgent need to develop more and better options for young people if they are to reach financial security as they navigate their way into adulthood.

We need investments and reforms along the entire education-to-employment pipeline, such as:

- Supporting young people in graduating from high school or earning an equivalent credential, both by preventing people from leaving before graduating and making it easy for them to re-engage if they leave.

- Ensuring there are accessible, affordable postsecondary options (including two- and four-year colleges, apprenticeships, and other kinds of career exposure, hands-on learning, and mentoring opportunities).

- Focusing on postsecondary completion in addition to access and enrollment.

- Building stronger bridges between school and work, with early exposure to mentors and workplaces.

- Developing systematized, easily accessible ways of awarding credit for prior learning, and awarding applied degrees that include work-based learning components.

- Delivering instruction that is designed around the needs of workers with other obligations (e.g., hybrid learning, online learning, modularized courses, micro-credentials, work-based learning, etc.).

We don’t have to start from scratch. Across the country, there are successful programs that are achieving these goals, but at nowhere near the scale required. We need to codify and share what works while also continuing to learn and build the evidence base. Some programs and approaches have been extensively evaluated, particularly in postsecondary education, such as combining ongoing enhanced advising services with financial support and other program reforms. There is also strong research supporting the effectiveness of job training programs targeting specific sectors and occupations—combining strong employer relationships with industry-relevant curriculum and support services.

Meanwhile, there is a deep body of knowledge and expertise undergirding programs serving young people who are not enrolled in traditional academic settings and not working (often called “opportunity youth”). Expanding opportunities to earn high school diplomas should be a priority, whether through high school re-engagement programs, alternative schools, or broader youth-serving programs. There are fewer formal evaluations of these types of programs, which can be partially traced to the scarcity of dedicated funding for opportunity youth programs—making it harder for them to reach the level of maturity, size, and stability needed for evaluations, not to mention that evaluations can be expensive. Support to establish and expand programs should be paired with robust efforts to measure and manage performance and build the evidence base.

As part of this work, state and local leaders will need to address how disconnected our K-12, postsecondary, and workforce development systems are—both from each other and the labor market. They have different incentives, rules, and governing structures, which makes it difficult to provide a smooth continuum of support from education to careers. Reforms are necessary not only at the program and institutional level, but at the policy level; we must reconfigure how education and labor market institutions partner with employers and job seekers to create a more functional, less fragmented system that is also more transparent for people to navigate. Importantly, this will include building out more applied learning options such as apprenticeships and other forms of work-based learning.

State and local governments must assume leadership on this issue. Fortunately, many already are. Yet governors, mayors, and school districts must double down, working with other partners such as community colleges, four-year colleges, unions, workforce boards, and community groups.

As our research shows, young adults face steep odds in achieving economic security and the ability to support themselves and their families. We do ourselves no favors by consigning millions of our young people to the economic margins at the very point when they should be charting their future and developing their talents. If we don’t do more to ensure their success, we all lose.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).