The U.S. has found itself in an age of mass imprisonment. Since 1980, the prison population has more than quadrupled. One in every 160 American adults is in prison.[1] More than half of black men without a high school degree do some jail time before they turn 30.[2]

But the winds may now be changing. Attorney General Eric Holder is encouraging federal prosecutors to disregard mandatory minimum sentences for low-level drug offenses. States like Kentucky and Texas are cutting prison populations by adopting alternative policies for nonviolent offenders. A shift away from mass imprisonment could mean serious savings—incarceration cost $80 billion in 2010[3]—but what might it mean for social mobility?

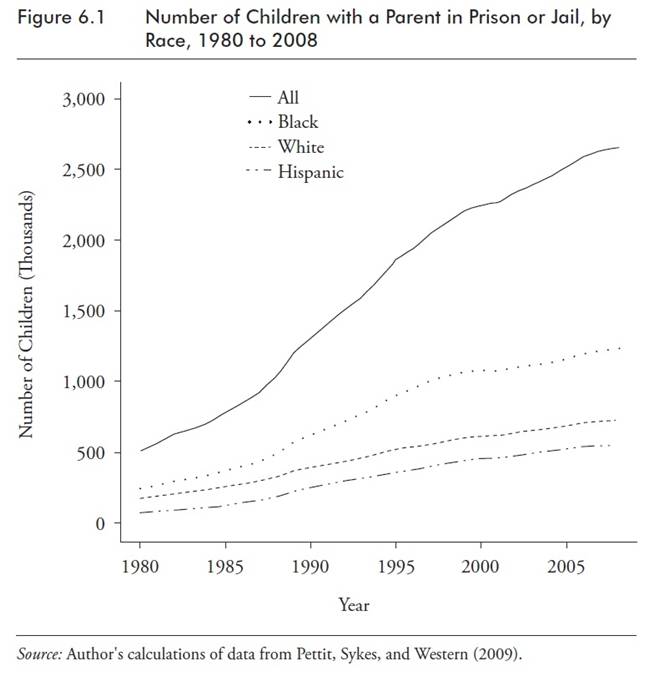

Intergenerational social mobility is a reflection of the way a child’s family circumstances determine their later life outcomes. There are plenty of children whose life chances could be affected by incarceration: half of all prisoners in the U.S. have children under age 18.[4] Of black children born in 1990, one in four had a father go to prison (compared to 1 in 25 white children).[5]

Since those who go to prison are disproportionately poor, black, and less educated, the average child of a parent at risk for jail time already has it pretty rough in terms of life chances: they are more likely to be in a low income household in a high risk neighborhood attending an underperforming school. Incarceration of a parent can add family instability, loss of household income, and stigma to any existing disadvantage.

Parental incarceration is associated with behavior issues—externalizing behavior, like temper tantrums—and later criminal activity, according to a series of studies using data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study. Children with a parent in prison also have higher rates of homelessness and infant mortality.[6] More generally, mass imprisonment contributes to increased single parenthood (see Charles Blow’s column for a vivid description), which is associated with worse academic and social outcomes, especially for boys.[7]

On the face of it, then, fewer parents in jail should mean better chances for their children. But it is not quite as simple as that. It is not clear that these incarcerated men (and some women) would actually be better spouses and parents were they at home instead of behind bars. A paper by Keith Finlay and David Neumark suggests that children would do no better living with their mother and crime-committing father than just with their never-married mother.[8] There’s also some evidence that fathers who have been in jail are much more likely to be physically abusive or to abuse drugs or alcohol.[9] In other words, there is a risk that efforts to reduce incarceration could actually hurt some children’s life chances, by keeping their criminal parent in the household.

So, the jury is out on what less incarceration will mean for the life chances of children with parents convicted of a crime. Lowering our incarceration rates may be very good for budgets and/or racial equality. But it is not, in itself, a pro-mobility policy. Children with parents at risk of going to jail are already living in jails without walls: their chances of success are much lower than children from stable, non-poor, more educated, white families.[10] Getting Dad out of jail is not going to drastically improve their life chances, unless we can also improve the quality of their home environment, education, and neighborhoods.

[1] Carson, E. A. & Golinelli, D. (2013). Prisoners in 2012: Advance counts. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; Bowie, C. (1982). Prisoners, 1925-1981. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

[2] Pettit, B. & Western, B. (2004). Mass imprisonment and the life course: Race and class inequality in U.S. incarceration. American Sociological Review 69, 151-169.

[3] Holder, E. (2013, August 12). Speech at the American Bar Association’s annual meeting in San Francisco

[4] Glaze, L. E. & Maruschak, L. M. (2008). Parents in Prison and Their Minor Children. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

[5] Wildeman, C. & Western, B. (2010). Incarceration in Fragile Families. The Future of Children 20(2), 157-177.

[6] Ibid, p. 168

[7] Autor, D. & Wasserman, M. (2013). Wayward sons: The emerging gender gap in labor markets and education. Third Way.

[8] Finlay, K. & Neumark, D. (2010). Is marriage always good for children? Evidence from families affected by incarceration. Journal of Human Resources 45(5), 1046-1088.

[9] Wildeman & Western, p. 164

[10] Sawhill, I. V., Winship, S., & Grannis, K. S. (2012). Pathways to the middle class: Balancing personal and public responsibilities. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, Social Genome Project.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Will Less Incarceration Mean More Social Mobility?

September 5, 2013