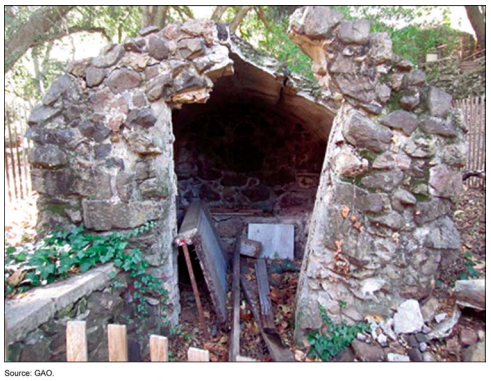

Consider the hut. Its real name is unknown. For all anyone knows, it might have been used as a storage shed or for some other purpose. The U.S. Department of Interior sought to get rid of the squat, 95-square-foot stone pile in 2010. It was crumbling and had not been used in years.

Alas, the DOI had no such luck. The federal land-disposal process requires buildings more than 50 years old, including this pile of rocks, to be evaluated for historic designation. The department was stuck using its limited resources to restore a structure that served no purpose.

Then there’s the confounding situation that surrounds the David W. Dyer Federal Building and U.S. Courthouse. Built in 1933, the Miami structure “is a skillful example of Mediterranean Revival architecture that combines Renaissance Revival elements with regional Florida architectural features,” according to the General Services Administration, which owns and manages real estate for most government agencies.

The feds cleared out of the Dyer building after the new $163 million Wilkie D. Ferguson Building opened next door in 2007. Over the following six years, Miami-Dade College repeatedly attempted to buy or lease the property. The Dyer building was never brought to market and the extended vacancy has caused damage that the GSA estimates would cost $60 million to correct. Tired of the delay, Rep. John Mica, R-Fla, introduced legislation two years ago to give the property to the college. The bill died in committee. Though the ornate courthouse remains empty today, taxpayers spend $1.2 million annually to maintain it.

These aren’t just anecdotes. The federal government’s property management problem is both longstanding and significant. Getting rid of unused and underutilized property is a particularly big problem, as was underscored at a Senate hearing this past week. The Government Accountability Office has had the GSA portfolio on its “high risk” list since 2003, a designation indicating vulnerability to “fraud, waste, abuse and mismanagement.”

According to the GAO, the federal government owns or leases 900,000 buildings and structures. GSA data from Fiscal Year 2014 report 735,000 buildings and structures. A Congressional Research Service report from 2010 estimates around 77,000 of them are vacant or underutilized. We can’t be sure if these numbers are right, the GAO told the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, as the GSA’s Federal Real Property Profile is not entirely reliable. The GSA’s property database is not readily accessible to either Congress or the public, although the GSA does post FRPP reports and some summary data.

Removing excess property from federal ownership should have broad appeal. Conservatives like shrinking government and everybody supports responsible stewardship of tax dollars. Entrepreneurs and the public can benefit from the redevelopment of federal properties, many of which are quite nice. (Some, like the 140-year-old pink octagonal monkey house in Dayton, Ohio, are more of an acquired taste.) Transferring federal property to private hands makes it taxable by local and state authorities, and when sold, it delivers additional funding to the treasury. Real property disposition also plays well in western states, where the feds control nearly half the land.

With budget caps in effect and appropriators threatening cuts, one might think that agencies would be in a hurry to offload unneeded buildings and property. Alas, such efforts have been halting. The GSA sold off just 342 unwanted properties in FY2014, according to testimony by Norman Dong, commissioner of the agency’s Public Buildings Service. That this number does not match the figure GSA reports in Table 15 here underscores the data-reporting mess.

It would be easy to attribute the slow pace of federal property sales to bureaucratic gaffes and that is one factor. The larger issue is that federal real property disposition is a mess because of well-intended policies that have aggregated over decades.

- The Federal Real Property and Administrative Services Act of 1949 forbids most agencies from putting up their properties for sale. Instead, they must work through GSA, which first offers the property to other federal agencies. This policy is intended to encourage rational management of the total federal real estate portfolio.

- The National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 directs agencies to register historic properties with GSA, a designation that means agencies must consult with assorted stakeholders as to what can be done with the structure.

- The National Environmental Protection Act of 1969 obliges agencies to assess the environmental impacts of a property disposal before disposing of the property.

- The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act of 1980 mandates agencies either clean up contaminated federal property before offloading it, or get assurance the new owner will do so. The Small Business Liability Relief and Brownfields Revitalization Act of 2002 amended CERCLA and established a brownfields rehab program. Unwanted federal properties with contamination may be slated into this program.

- The Stewart B. McKinney Homeless Assistance Act of 1987 requires agencies to offer surplus property for use by entities aiding the homeless. Since 1987, only 122 properties of the 40,000 buildings that were screened ended up being transferred to nonprofits aiding the homeless.

These are just some of the statutes that come into play. Collectively, these policies mean it takes years to dispense with unwanted federal buildings. Offloading them necessitates surmounting numerous hurdles and can inflict upfront costs for repair and clean-up. Agencies often face incentives to do nothing.

An unintended and particularly distressing effect of this policy aggregation is demolition by neglect. Shuttered properties crumble, meaning agencies face higher repair costs before they can dispose of them. This makes them less likely to be repaired and sold. The Department of Veterans Affairs, for example, has numerous derelict properties that cost money to maintain. This destruction of public wealth has fueled more than a few media horror stories.

Congress has been working on a number of bills to improve matters for some years. There has been discussion of a BRAC-type commission, a fast-track process for removing the most valuable properties or devoting 2 percent of the proceeds from property sales to homeless assistance. Some members have introduced legislation directing agencies to convey specific properties to private hands.

None of the systemic reforms have come close to enactment. Real property reform is a complex, “good government” issue that does not strike legislators as an election-winner. Any real property reform bill also must respect, or at least not offend, the various values at play (such as historic preservation) while giving agencies clear incentives to participate and making the whole process more prompt and less wasteful.

Commentary

Why can’t the federal government sell unneeded real property more quickly?

June 24, 2015