A Response to the U.S. Office of Science and Technology Policy

Innovation districts are springing up in cities across the country. Unlike traditional science parks and suburban innovation corridors, these districts cluster cutting edge research institutions, R&D intensive companies, entrepreneurial firms and business incubators in small geographic areas that are livable, walkable, bike-able, and transit connected. They incorporate both the new collaborative workings of the “open innovation” economy as well as new market and demographic preferences for quality places.

In our analysis of this growing movement, we tend to focus on the role that local actors have played in the development of these areas. For this reason, the federal government should not attempt to lead the development of innovation districts. Successful districts do not emerge from a federal program like empowerment zones but rather from the collaborative efforts of local institutions and leaders and organic market dynamics. In addition, the emerging districts around the country differ markedly in their leadership structure, sector orientation, and existing economic, physical and networking assets—obviating any one “one size fits all” response.

Still, the federal government clearly has a role to play and should focus its support on three main inputs to successful innovation districts:

Basic and Applied Research

While the most advanced districts around the country are created by networks of regional stakeholders—local governments, universities, private businesses, entrepreneurs, real estate developers, and civic institutions—the federal government provides a strong foundation through its funding of basic and applied research. Many innovation districts are centered around a major anchor institution, which tend to rely heavily on federal dollars to support their research. MIT, for example, relies on the federal government for roughly 70 percent of its research funding—$466 million in 2013. This federally-backed research creates a platform for commercialization, which spurs job creation and entrepreneurial growth and brings technological advances to our businesses and homes.

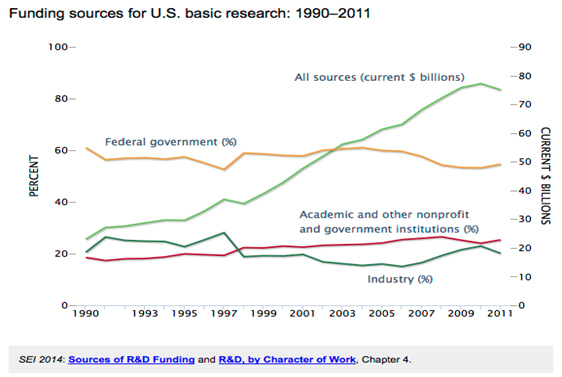

However, in recent years, federal support for basic research has begun to slip, and the growth trajectory of R&D spending has suffered. At a time when sequestration cuts and budget pressures further threaten the U.S. R&D base, federal leaders must recommit to funding this basic research.

An encouraging sign is the federal government’s increasing support of applied research. One example is the continued progress of the National Network of Manufacturing Institutes, innovation hubs that have won $240 million in federal funding and are specifically tasked with integrating into regional economic clusters.

The recent decision to locate the American Lightweight Metals Manufacturing Institute in the core of Detroit is particularly heartening. This type of location decision has the potential to not only spur innovative commercialization and strengthen an important regional cluster but also to supercharge the revitalization of communities though the growth of housing, retail establishments and quality place-making.

In addition to allocating grants and providing funding for R&D, the federal government itself conducts R&D through a network of federal research laboratories. We can maximize the return on this investment by co-locating federal research facilities—or at the very least, smaller outposts of major federal labs—in close proximity to research universities, private industry, and start-ups. Much of the research performed at federal labs is remote for reasons of security or secrecy; still, there are opportunities to integrate and collaborate more closely with regional clusters.

Skilled Workers

Innovation districts—and the innovation economy more broadly—rely upon a technically skilled workforce, specifically those in the STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) fields. The federal government can do a number of things to support this. By implementing something akin to my Race to the Shop proposal (a version of which is currently being developed by Delaware Sen. Chris Coons) the federal government could encourage a more robust school-to-work pipeline for sub-baccalaureate workers. Given the proximity of innovation districts to low-income neighborhoods (and, in some cities, public and affordable housing developments), there is the demand for targeted federal efforts to underwrite STEM-oriented schools that offer apprenticeship opportunities.

The trend toward locating community colleges amid burgeoning Innovation Districts (e.g., Houston Community College at the Texas Medical Center Baltimore Community College at University of Maryland BioPark) offers the mutual benefit of connecting sub-baccalaureate students with real-world training and connections to potential future employers.

At a more macro level, reforming our nation’s immigration system, particularly in attracting and retaining highly skilled foreigners, should also be a top priority.

Infrastructure and Housing

Unlike traditional science parks and suburban innovation corridors, innovation districts, like the cities and urban communities that house them, need effective transit systems, adequate mixed-income housing and mixed-use development to succeed. Many innovation districts have already used a variety of federal resources for these purposes to great effect. After years of budget cuts and legislative drift, the primary imperative is to reestablish the federal government as a reliable, consistent, and flexible partner in these arenas, both with regard to tax incentives (e.g., the New Markets Tax Credit) and discretionary and credit enhancement programs around housing, transportation, and sustainable development.

In addition to these platform-setting approaches for the federal government, there are smaller actions that can make the feds more supportive to local efforts. Take, for example, Cambridge, Mass., which contains a leading innovation district. In an attempt to remain affordable for start-ups and entrepreneurs, the city recently passed a zoning law mandating 5 percent of new office space be reserved for short-term and shared “innovation space.” At the same time, the federal government is redeveloping a DOT campus in the district, adding significant office space in a constrained market, but exempting the federal land from the local zoning law. Simply by voluntarily submitting to the local zoning, the federal government would be greatly supporting the innovation ecosystem.

In summary, the federal government did not start the rise of innovation districts but it could help accelerate this encouraging dynamic and broaden the impact on innovative growth, urban revitalization, and social opportunity. It should do so in a humble way – doing what cities and metro areas can’t (e.g., providing a strong national platform for research and innovation) and providing support that is respectful of local variation and supportive of local networks and ecosystems. At a time when the nation still needs more and better jobs, smart federal action would spur not only high levels of job growth, business formation, and commercialization but also urban regeneration that works for local residents and communities. It would also test a new form of federalism, where cities and metro areas lead and the federal government follows. It would even make the federal government more efficient by providing a higher level of market and social return on discrete federal investments and integrating the otherwise fragmented flow of federal resources. All of this could amount to what former HUD Secretary Henry Cisneros called a “two-plus-two-equals-five” effect.