Why Focus on Teen Pregnancy?

Virtually all of the growth of single-parent families in recent decades has been driven by an increase in births outside marriage. Divorce rates have leveled off or declined modestly since the early 1980s and thus have not contributed to the rising proportion of children being raised by only one parent nor to the increase in child poverty and welfare dependence associated with the rise in single-parent families.

Not all non-marital births are to teen-agers. In fact, 70 percent of all births outside marriage are to women over age 20. For this reason, some argue that a focus on teens fails to address the real problem and that much more attention needs to be given to preventing childbearing, or raising marriage rates, among single women who have already entered their adult years.

But there are at least four reasons to focus on teens:

First, although a large proportion of non-marital births is to adult women, half of first non-marital births are to teens. Thus, the pattern tends to start in the teenage years, and, once teens have had a first child outside marriage, many go on to have additional children out of wedlock at an older age. A number of programs aimed at preventing subsequent births to teen mothers have been launched but few have had much success. So, if we want to prevent out-of-wedlock childbearing and the growth of single-parent families, the teenage years are a good place to start

Second, teen childbearing is very costly. A 1997 study by Rebecca Maynard of Mathematica Policy Research in Princeton, New Jersey, found that, after controlling for differences between teen mothers and mothers aged 20 or 21 when they had their first child, teen childbearing costs taxpayers more than $7 billion a year or $3,200 a year for each teenage birth, conservatively estimated.

Third, although almost all single mothers face major challenges in raising their children alone, teen mothers are especially disadvantaged. They are more likely to have dropped out of school and are less likely to be able to support themselves. Only one out of every five teen mothers receives any support from their child’s father, and about 80 percent end up on welfare. Once on welfare, they are likely to remain there for a long time. In fact, half of all current welfare recipients had their first child as a teenager.

Some research suggests that women who have children at an early age are no worse off than comparable women who delay childbearing. According to this research, many of the disadvantages accruing to early childbearers are related to their own disadvantaged backgrounds. This research suggests that it would be unwise to attribute all of the problems faced by teen mothers to the timing of the birth per se. But even after taking background characteristics into account, other research documents that teen mothers are less likely to finish high school, less likely to ever marry, and more likely to have additional children outside marriage. Thus, an early birth is not just a marker of preexisting problems but a barrier to subsequent upward mobility. As Daniel Lichter of Ohio State University has shown, even those unwed mothers who eventually marry end up with less successful partners than those who delay childbearing. As a result, even if married, these women face much higher rates of poverty and dependence on government assistance than those who avoid an early birth. And early marriages are much more likely to end in divorce. So marriage, while helpful, is no panacea.

Fourth, the children of teen mothers face far greater problems than those born to older mothers. If the reason we care about stemming the growth of single-parent families is the consequences for children, and if the age of the mother is as important as her marital status, then focusing solely on marital status would be unwise. Not only are mothers who defer childbearing more likely to marry, but with or without marriage, their children will be better off. The children of teen mothers are more likely than the children of older mothers to be born prematurely at low birth weight and to suffer a variety of health problems as a consequence. They are more likely to do poorly in school, to suffer higher rates of abuse and neglect, and to end up in foster care with all its attendant costs.

How Does Current Welfare Law Address Teen Pregnancy and Non-Marital Births?

The welfare law enacted in 1996 contained numerous provisions designed to reduce teen or out-of-wedlock childbearing including:

- A $50 million a year federal investment in abstinence education;

- A requirement that teen mothers complete high school or the equivalent and live at home or in another supervised setting;

- New measures to ensure that paternity is established and child support paid;

- A $20 million bonus for each of the 5 states with the greatest success in reducing out-of-wedlock births and abortions;

- A $1 billion performance bonus tied to the law’s goals, which include reducing out-of-wedlock pregnancies and encouraging the formation and maintenance of two-parent families;

- The flexibility for states to deny benefits to teen mothers or to mothers who have additional children while on welfare (no state has adopted the first but 23 states have adopted the second); and

- A requirement that states set goals and take actions to reduce out-of-wedlock pregnancies, with special emphasis on teen pregnancies.

Research attempting to establish a link between one or more of these provisions and teen out-of-wedlock childbearing has, for the most part, failed to find a clear relationship. One exception is child support enforcement, which appears to have had a significant effect in deterring unwed childbearing.

Are Teen Pregnancies and Births Declining?

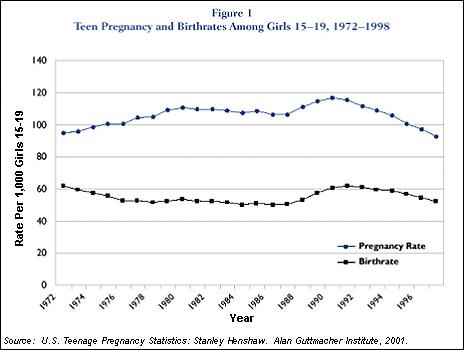

Teen pregnancy and birthrates have both declined sharply in the 1990s (figure 1). The fact that these declines predated the enactment of federal welfare reform suggests that they were caused by other factors. However, it is worth noting that many states began to reform their welfare systems earlier in the decade under waivers from the federal government, so we cannot be sure. In addition, the declines appear to have accelerated in the second half of the decade after welfare reform was enacted. And finally, most of the decline in the early 1990s was the result of a decrease in second or higher order births to women who were already teen mothers. This decrease was related in part to the popularity of new and more effective methods of birth control among this group. It was not until the second half of the decade that a significant drop in first births to teens occurred.

Teen birthrates had also declined in the 1970s and early 1980s but in this earlier period all of the decline was due to increased abortion. Significantly, all of the teen birthrate decreases in the 1990s were due to fewer pregnancies, not more abortions.

Equally significant is the fact that teens are now having less sex. Up until the 1990s, despite some progress in convincing teens to use contraception, teen pregnancy rates continued to rise because an increasing number of teens were becoming sexually active at an early age, thereby putting themselves at risk of pregnancy. More recently, both better contraceptive use and less sex have contributed to the lowering of rates.

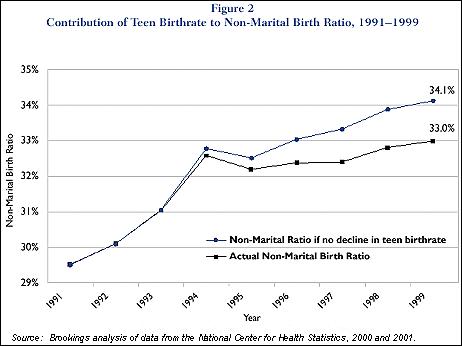

Given that four out of five teen births are to an unwed mother, this drop in the teen birthrate contributed to the leveling off of the proportion of children born outside marriage after 1994 (figure 2). More specifically, if teen birthrates had held at the levels reached in the early 1990s, by 1999 this proportion would have been more than a full percentage point higher. Thus, a focus on teenagers has a major role to play in future reductions of both out-of-wedlock childbearing and the growth of single-parent families.

What Caused the Decline in Teen Pregnancies and Births?

Although the immediate causes of the decline-less sex and more contraception-are relatively well established, it is less clear what might have motivated teens to choose either one. However, many experts believe it was some combination of greater public and private efforts to prevent teen pregnancy, the new messages about work and child support embedded in welfare reform, more conservative attitudes among the young, fear of AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases, the availability of more effective forms of contraception, and perhaps the strong economy.

Some of these factors have undoubtedly interacted, making it difficult to ever sort out their separate effects. For example, fear of AIDS may have made teenagers-males in particular, for whom pregnancy has traditionally been of less concern-more cautious and willing to listen to new messages. Indeed, as shown by Leighton Ku and his colleagues at the Urban Institute in Washington, D.C., the proportion of adolescent males approving of premarital sex decreased from 80 percent in 1988 to 71 percent in 1995. The Ku study also linked this shift in adolescent male attitudes to a change in their behavior.

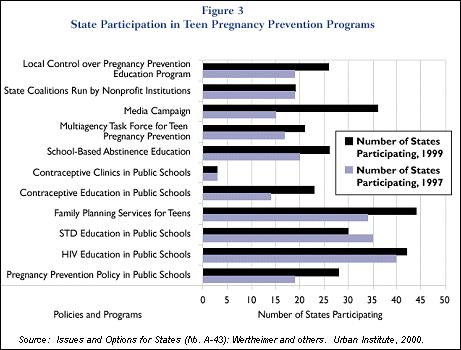

The growth of public and private efforts to combat teen pregnancy may have also played a role, as suggested by surveys conducted by the National Governors’ Association, the General Accounting Office, the American Public Human Services Association, and most recently and comprehensively, by Child Trends. The Child Trends study, conducted by Richard Wertheimer and his associates at the Urban Institute, surveyed all 50 states in both 1997 and 1999. The survey shows that states have dramatically increased their efforts to reduce teen pregnancy (figure 3). These efforts include everything from the formation of statewide task forces to more emphasis on sex education in the public schools and statewide media campaigns. Although such efforts have been greatly expanded in recent years, they are still relatively small. State spending on teen pregnancy prevention averages only about $8 a year per teenaged girl. In addition to being small, such efforts may or may not be effective in preventing pregnancy. Fortunately, we know more about this topic now than we did even a few years ago.

Do Teen Pregnancy Prevention Programs Work?

The short answer is “yes, some do.” Based on a careful review of the scholarly literature completed by Douglas Kirby of ETR Associates in Santa Cruz, California, a number of rigorously evaluated programs have been found to reduce pregnancy rates. Two of these programs have reduced rates by as much as one-half. One is a program that involves teens in community service with adult supervision and counseling. The other includes a range of services such as tutoring and career counseling along with sex education and reproductive health services. Both have been replicated in diverse communities and evaluated by randomly assigning teens to a program and control group. In addition, a number of less intensive and less costly sex education programs have also been found to be effective in persuading teens to delay sex and/or use contraception. Such programs typically provide clear messages about the importance of abstaining from sex and/or using contraception, teach teens how to deal with peer pressure to have sex, and provide practice in communicating and negotiating with partners.

“Abstinence only” programs are relatively new and have not yet been subject to careful evaluation, although what research exists has not been encouraging. More importantly, the line between abstinence only and more comprehensive sex education that advocates abstinence but also teaches about contraception is increasingly blurred. What matters is not so much the label but rather what a particular program includes, what the teacher believes, and how that plays out in the classroom. A strong abstinence message is totally consistent with public values, but the idea that the federal government can, or should, rigidly prescribe what goes on in the classroom through detailed curricular guidelines makes little sense. Family and community values, not a federal mandate, should prevail, especially in an area as sensitive as this one.

Do Media Campaigns Work?

Community-based programs are only part of the solution to teen pregnancy. Indeed, only 10 percent of teens report they have participated in such a program (outside of school), while on average teens spend more than 38 hours a week exposed to various forms of entertainment media. By themselves, teen pregnancy prevention programs cannot change prevailing social norms or attitudes that influence teen sexual behavior. The increase in teen pregnancy rates between the early 1970s and 1990 was largely the result of a change in attitudes about the appropriateness of early premarital sex, especially for young women. As more and more teen girls put themselves at risk of an early pregnancy, pregnancy rates rose. More recently, efforts to encourage teens to take a pledge not to have sex before marriage have had some success in delaying the onset of sex.

In an attempt to influence these attitudes and behaviors, several national organizations as well as numerous states have turned to the media for assistance. Between 1997 and 1999 alone, the number of states conducting media campaigns increased from 15 to 36. Typically, such campaigns use both print and electronic media to reach large numbers of young people with messages designed to change their behavior. Such messages can be delivered via public service announcements (PSAs) or by working with the media to incorporate more responsible content into their ongoing programming. Most state efforts rely on PSA campaigns but several national organizations are working with the entertainment industry to affect content.

Research assessing the effectiveness of media campaigns is less extensive and less widely known than research evaluating community-based programs, but it shows that they, too, can be effective. A meta-analysis of 48 different health-related media campaigns from smoking cessation to AIDS prevention by Leslie Snyder of the University of Connecticut found that, on average, such campaigns caused 7 to 10 percent of those exposed to the campaign to change their behavior (relative to those in a control group). As with community-based programs, media campaigns vary enormously in their effectiveness and need to be designed with care. But existing evidence suggests that they are a good way to reach large numbers of teens inexpensively.

Are Efforts to Reduce Teen Pregnancy Cost-Effective?

At first appearance, the finding by Rebecca Maynard that each teen mother costs the government an average of $3,200 per year suggests that government could spend as much as $3,200 per teen girl on teen pregnancy prevention and break even in the process. But, of course, not all girls become teen mothers and programs addressing this problem are not 100 percent effective so a lot of this money would be wasted on girls who do not need services and on programs that are less than fully effective.

Here is a simple but useful method to estimate how much money could be spent on teen pregnancy prevention programs and still realize benefits that exceed costs. If we accept Maynard’s estimate that reducing teen pregnancy saves $3,200 per birth prevented (in 2001 dollars), the question is how much should we spend to prevent such births? We first have to adjust the $3,200 estimate for the fact that not all teen girls will get pregnant and give birth without the intervention program. We know that about 40 percent of teen girls become pregnant and about half of these (or 20 percent) give birth. This adjustment yields the estimate that $640 (20 percent multiplied by $3,200) might be saved by a universal prevention program. (If we knew how to target the young people most at risk we could save even more than this.) However, a second adjustment is necessary because not all intervention programs are effective. Based on data reviewed by Douglas Kirby and by Leslie Snyder, a good estimate is that about one out of every ten girls enrolled in a program or reached by a media campaign might change her behavior in a way that delayed pregnancy beyond her teen years. This second adjustment yields the estimate that universal programs would produce a benefit of 10 percent of $640 or about $64 per participant. As the Wertheimer survey showed, actual spending on teen pregnancy prevention programs in the entire nation now averages about $8 per teenage girl. If the potential savings are $64 per teenage female while actual current spending is only $8 per teenage female, government is clearly missing an opportunity for productive investments in prevention programs. In fact, these calculations-while rough-suggest that government could spend up to eight times ($64 divided by $8) as much as is currently being spent and still break even.

Implications for Welfare Reform Reauthorization Research and experience over the last decade suggest several lessons for the administration and Congress as they consider reauthorization of the 1996 welfare reform legislation.

First, the emphasis in the current law on time limits, work, and child support enforcement should be maintained. The 1996 welfare reform law included a set of very important messages. To young women, it said “if you become a mother, this will not relieve you of an obligation to finish school and support yourself and your family through work or marriage. And any special assistance you receive will be time limited.” To young men, it said “if you father a child out-of-wedlock, you will be responsible for supporting that child.” Although opinions vary as to whether these messages have had an impact, in my view the decline in teen pregnancies and births together with the leveling off of the non-marital birth ratio and of the proportion of children living in single parent homes all suggest such an impact. These messages may be far more important than any specific provisions aimed at increasing marriage or reducing out-of-wedlock childbearing, and their effects are likely to cumulate over time.

Second, the federal government should fund a national resource center to collect and disseminate information about what works to prevent teen pregnancy. Until recently, little information was available about the best ways to prevent teen pregnancy. States and communities had no way of learning about each other’s efforts and teens themselves had no ready source of information about the risks of pregnancy and the consequences of early unprotected sex. Some private organizations have attempted to fill the gap without much help from public sources.

Third, Congress should send a strong abstinence message coupled with education about contraception. Surveys of both adults and teens reveal strong support for abstinence as the preferred standard of behavior for school-age youth, and they want teens to hear this message. At the same time, a majority is in favor of making birth control services and information available to teens who are sexually active. In addition, few expect all unmarried adults in their twenties to abstain from sex until marriage. And since a large proportion of non-marital births occurs in this age group, and a significant number of teens continue to be sexually active, education about and access to reproductive health services remains important through Title X of the Public Health Service Act, the Medicaid program, and other federal and state programs.

Fourth, adequate resources should be provided to states to prevent teen pregnancy, without specifying the means for achieving this goal. In addition, states that work successfully to reduce teen pregnancy should be rewarded for their efforts. A strong argument can be made that the federal government should specify the outcomes it wants to achieve but not prescribe the means for achieving them. This is especially important given some uncertainty about the effectiveness of different programs and strategies, and the diversity of opinion about the best way to proceed. It suggests the wisdom of retaining a block grant structure for TANF and avoiding earmarks for specific programs. This does not mean the federal government should not reward states that achieve certain objectives, such as an increase in the proportion of children living in two-parent families, a decline in the non-marital birth ratio, or a decline in the teen pregnancy or birth rate. Reducing early childbearing may be one of the most effective ways of increasing the proportion of children born to, and raised by, a married couple. But states should decide on the best way to achieve these outcomes, subject only to the caveat that they base their efforts on reliable evidence about what works. The evidence presented above suggests that states should be spending roughly eight times as much as they are now on teen pregnancy prevention.

Fifth, the federal government should fund a national media campaign. Too many public officials and community leaders have assumed that if they could just find the right program, teen pregnancy rates would be reduced. Although there are now a number of programs that have proved effective, the burden of reducing teen pregnancy should not rest on programs alone. Rather, we should build on the fledgling efforts undertaken at the state and national level over the past five years to fund a broad-based, sophisticated media campaign to reduce teen pregnancy. These funds should support not only public service ads but also various nongovernmental efforts to work in partnership with the entertainment industry to promote more responsible content. These media efforts can work in tandem with effective sex education and more expensive and intensive community level programs targeted to high-risk youth.

Conclusion

These steps have the potential to maintain the progress made over the past decade in reducing teen and out-of-wedlock pregnancies. There are only two solutions to the problem of childbearing outside marriage. One is to encourage early marriage. The other is to encourage delayed childbearing until marriage. Although commonplace as recently as the 1950s, early marriage is no longer a sensible strategy in a society where decent jobs increasingly require a high level of education and where half of teen marriages end in divorce. If we want to ensure that more children grow up in stable two-parent families, we must first ensure that more women reach adulthood before they have children.

Additional Reading

Henshaw, Stanley. 2001. U.S. Teenage Pregnancy Statistics. New York: Alan Guttmacher Institute.

Kirby, Douglas. 2001. Emerging Answers: Research Findings on Programs to Reduce Teen Pregnancy. Washington, D.C.: National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy.

Ku, Leighton, and others. 1998. “Understanding Changes in Sexual Activity Among Young Metropolitan Men: 1979-1995.” Family Planning Perspectives, 30(6): 256-262.

Lichter, Daniel T., Deborah Roempke Graefe, and J. Brian Brown. 2001. Is Marriage a Panacea? Union Formation Among Economically Disadvantaged Unwed Mothers. Columbus: Ohio State University.

Maynard, Rebecca A., ed. 1997. Kids Having Kids: Economic Costs and Social Consequences of Teen Pregnancy. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute.

National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy. 2001. Halfway There: A Prescription for Continued Progress in Preventing Teen Pregnancy. Washington, D.C..

National Center for Health Statistics. 2000 and 2001. National Vital Statistics Reports, 48 and 49, various issues. Hyattsville, Md.: Department of Health and Human Services.

Sawhill, Isabel. Forthcoming. “Welfare Reform and the Marriage Movement.” Public Interest.

Snyder, Leslie B. 2000. “How Effective Are Mediated Health Campaigns?” In Public Communication Campaign, edited by Ronald E. Rice and Charles K. Atkin. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage.

Wertheimer, Richard, Justin Jager, and Kristin Anderson Moore. 2000. “State Policy Initiatives for Reducing Teen and Adult Non-Marital Childbearing.” New Federalism: Issues and Options for States (No. A-43). Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute.