Four years after its creation in the 2014 constitution, Tunisia’s Constitutional Court remains vacant. Tunisia, the one democracy to emerge from the Arab Spring, has been unable to find agreement on the 12 judges of the court. Today, Tunisia needs to prioritize the court’s creation in order to lock in its democratic reforms ahead of the 2019 elections.

The absence of a constitutional court was felt acutely this month, when President Beji Caid Essebsi rejected Prime Minister Youssef Chahed’s proposed cabinet reshuffle. By most readings of the constitution, Chahed did not need Essebsi’s consent, as the reshuffle did not include the ministers of defense or foreign affairs. But Tunisia had no constitutional court to adjudicate the competing claims. Thankfully, Essebsi chose to put country over party and swore in Chahed’s cabinet on November 14. While Tunisia avoided a constitutional crisis, the episode highlighted the need for a constitutional court.

Under the former dictatorship of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, Tunisia had a Constitutional Council, but it was dissolved in the wake of the 2011 revolution that ousted Ben Ali. Initially, the lack of a constitutional court held over from autocracy was a structural advantage for Tunisia’s transition to democracy. In Egypt, for instance, a Supreme Constitutional Court that had been packed with supporters of the former dictatorship dissolved both the democratically-elected parliament and the constituent assembly. In Tunisia, had Ben Ali’s Constitutional Council also been held over, it may have likewise dissolved its country’s constituent assembly, which had overstayed its pledged one-year mandate. Such a ruling would have plunged Tunisia’s transition into an even deeper political crisis than it already had.

Instead, the constituent assembly remained and completed Tunisia’s new constitution in 2014. That constitution mandated the creation of a constitutional court in one year. In the meantime, Tunisia created a temporary body—the “Provisional Instance to Review the Constitutionality of Draft Laws”—but it can rule only on draft laws and cannot, for instance, adjudicate disputes over the president and prime minister’s powers. To create the Constitutional Court, the parliament, the president, and the Supreme Judicial Council—an independent body overseeing the appointment and promotion of judges—must each appoint four of the 12 judges of the court.

Almost five years later, only one judge has been confirmed by the parliament. Part of the problem is that choosing the judges is a very difficult, polarizing process, just like it is in the United States. But part of it may also have stemmed from the ruling coalition’s desire to avoid polarizing issues in the name of stability and consensus.

The lack of a court has been a tremendous loss for Tunisia’s democracy. Without this check on the ruling coalition, the Tunisian government was able to pass a series of problematic laws, most notably a restrictive counterterrorism law and a blanket amnesty for corrupt officials from the Ben Ali regime. Had a true court been in place, it may have been able to challenge the constitutionality of these laws. Article 80 of the constitution also empowers the constitutional court to end states of emergency, which the Tunisian government has repeatedly invoked in its heavy-handed war on terrorism.

Over the next year, the need for a constitutional court is likely only to grow. As a result of the cabinet reshuffle, President Essebsi and Prime Minister Chahed now come from two entirely different power bases. That divided government sets the stage for future tensions regarding the distribution of power between the two executives. Having a constitutional court would be an important step in resolving such power disputes.

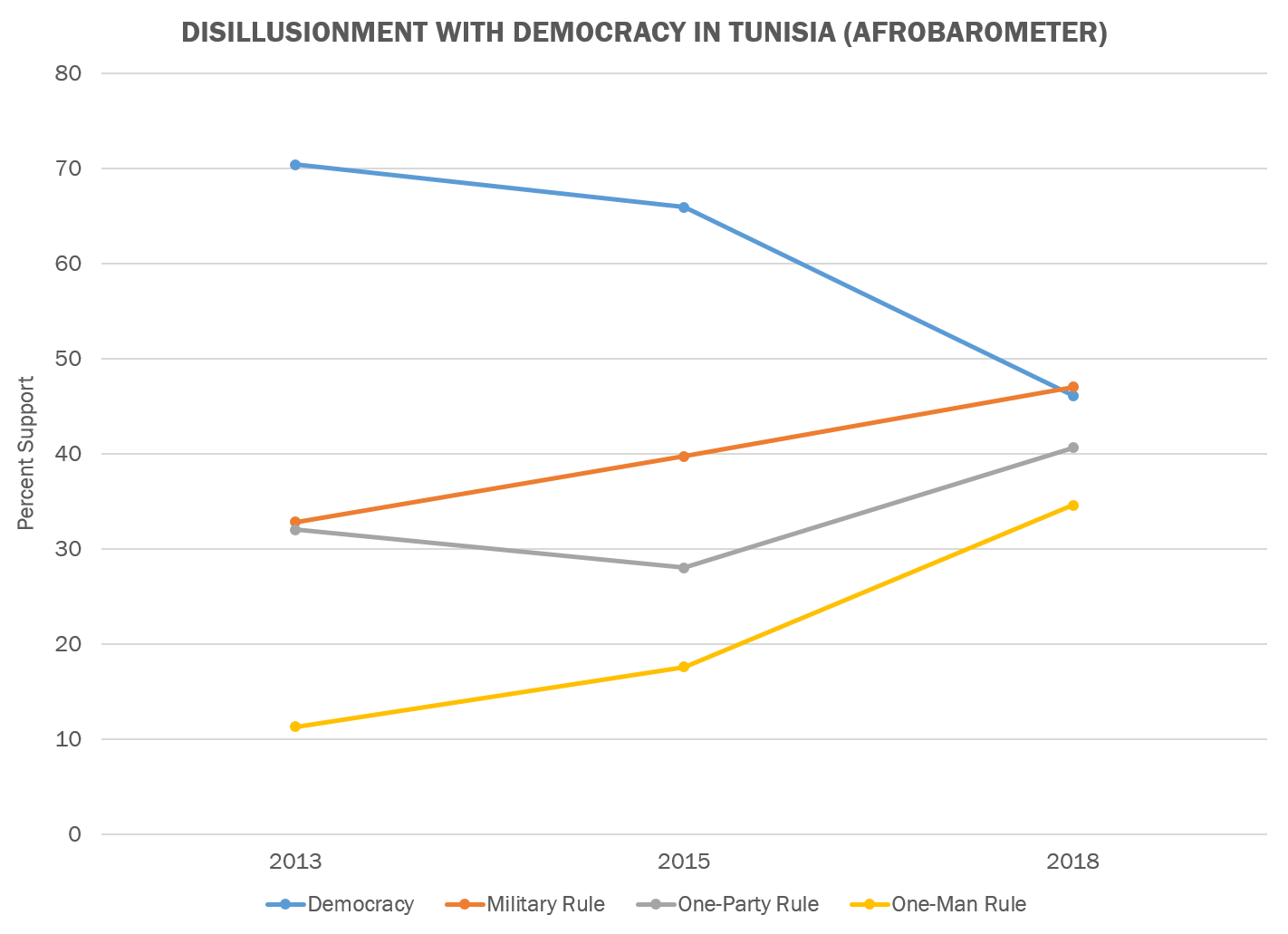

Perhaps the most important reason for such a court is even more forward-looking: to lock in Tunisia’s democratic progress before the 2019 parliamentary and presidential elections. While the candidates have not yet been declared, the conditions may be ripe for the emergence of a populist strongman. Tunisians have become increasingly frustrated with democracy for failing to improve the economy. According to an Afrobarometer survey, only 46 percent of Tunisians today find democracy to be the most preferable form of a government, down from 70 percent in 2013. Meanwhile, support has grown considerably for military rule (47 percent), one-party rule (41 percent), and a strongman who “abolishes the parliament and elections” entirely (35 percent).

To prevent Tunisia from following the path of Brazil, Turkey, Hungary, and so many other backsliding democracies today, the Tunisian government must prioritize the creation of the Constitutional Court. A court with professional, pro-democracy judges could be crucial to ensuring that a future president remains loyal to Tunisia’s progressive constitution and preserves its status as the one success story of the Arab Spring. Tunisia cannot afford to wait any longer in creating the Constitutional Court.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Tunisia needs a constitutional court

November 20, 2018